Crocodile

Animal

Series editor: Jonathan Burt

Already published

Ant Charlotte Sleigh Ape John Sorenson Bear Robert E. Bieder

Bee Claire Preston Camel Robert Irwin Cat Katharine M. Rogers

Chicken Annie Potts Cockroach Marion Copeland Cow Hannah Velten

Crocodile Dan Wylie Crow Boria Sax Dog Susan McHugh

Donkey Jill Bough Duck Victoria de Rijke Eel Richard Schweid

Elephant Dan Wylie Falcon Helen Macdonald Fly Steven Connor

Fox Martin Wallen Frog Charlotte Sleigh Giraffe Edgar Williams

Hare Simon Carnell Horse Elaine Walker Hyena Mikita Brottman

Kangaroo John Simons Leech Robert G. W. Kirk and Neil Pemberton

Lion Deirdre Jackson Lobster Richard J. King Monkey Desmond Morris

Moose Kevin Jackson Mosquito Richard Jones Ostrich Edgar Williams

Otter Daniel Allen Owl Desmond Morris Oyster Rebecca Stott

Parrot Paul Carter Peacock Christine E. Jackson Penguin Stephen Martin

Pig Brett Mizelle Pigeon Barbara Allen Rat Jonathan Burt

Rhinoceros Kelly Enright Salmon Peter Coates Shark Dean Crawford

Snail Peter Williams Snake Drake Stutesman Sparrow Kim Todd

Spider Katja and Sergiusz Michalski Swan Peter Young Tiger Susie Green

Tortoise Peter Young Trout James Owen Vulture Thom Van Dooren

Whale Joe Roman Wolf Garry Marvin

Crocodile

Dan Wylie

| REAKTION BOOKS |  |

Published by

REAKTION BOOKS LTD

33 Great Sutton Street

London EC1V 0DX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2013

Copyright Dan Wylie

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers.

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgments and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in China by C&C Offset Printing Co., Ltd

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Wylie, Dan

Crocodile. (Animal)

1. Crocodilians.

I. Title II. Series

597.98-DC23

eISBN: 9781780231235

Contents

The Survivor

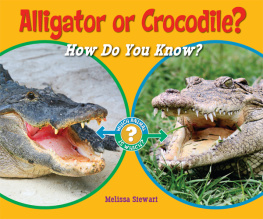

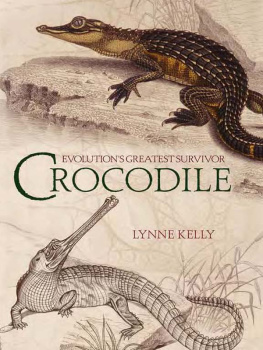

The title of this book is misleading. It should really be Crocodilian, since it explores not only what are sometimes called true crocodiles, but the closely related species of alligators, caimans and gharials. The latter are not false crocodiles, but equally respectable members of the same family. Today there are at least 23 recognized crocodilian species, roaming the waters of the globe from Brazil to Bali, from Florida to Formosa, from the Congo to China. They have done so, in some or other shape, since before our familiar continents were even formed, since before the great extinction event some 65 million years ago that eradicated the dinosaurs. They are truly among the evolving Earths most extraordinary survivors. Only now, as humans hunt them to the brink of extinction and destroy their habitats, are some crocodilian species beginning to be in serious danger of vanishing.

It doesnt help, of course, that they persist in eating people; many humans still regard their cold-blooded, predatory life-ways as excuse enough to vilify them, kill them, eat them, and turn them into handbags and shoes. If there is a single word most commonly associated with crocodiles, it is infested: crocodile habitats are described, with numbing regularity, as crocodile-infested waters. Hugh Stayt wrote in 1968:

Yet, surprisingly often, crocodilians have been worshipped, appealed to, represented and treasured, albeit almost always with a tinge of fearfulness. For tens of thousands of years, Africans, Australasian Aboriginals and early Americans incorporated reverence and propitiation of crocodilians into their animistic mythologies and rituals. Only more recently have the biblical, Cartesian and Kantian strains of Western philosophy designated animals as merely tools for human use with appalling consequences for them. Yet even in Europe, where crocodiles have not lived in the wild in human memory, there has been a counter-discourse. Porphyry of Tyre (234c. 305 CE) suggested:

If we define, by utility, things which pertain to us, we shall not be prevented from admitting that we were generated for the sake of the most destructive animals, such as crocodiles.

Even in our secular, technologized era, crocodilians remain an unsettling reminder of humans natural vulnerability. We have used them deplorably, even as we newly appreciate their ecological importance. Hence an important theme of this book is human cultures difficult, entangled progression from fear of crocodiles, to fear for them.

How did crocodilians survive so long, essentially unchanged?

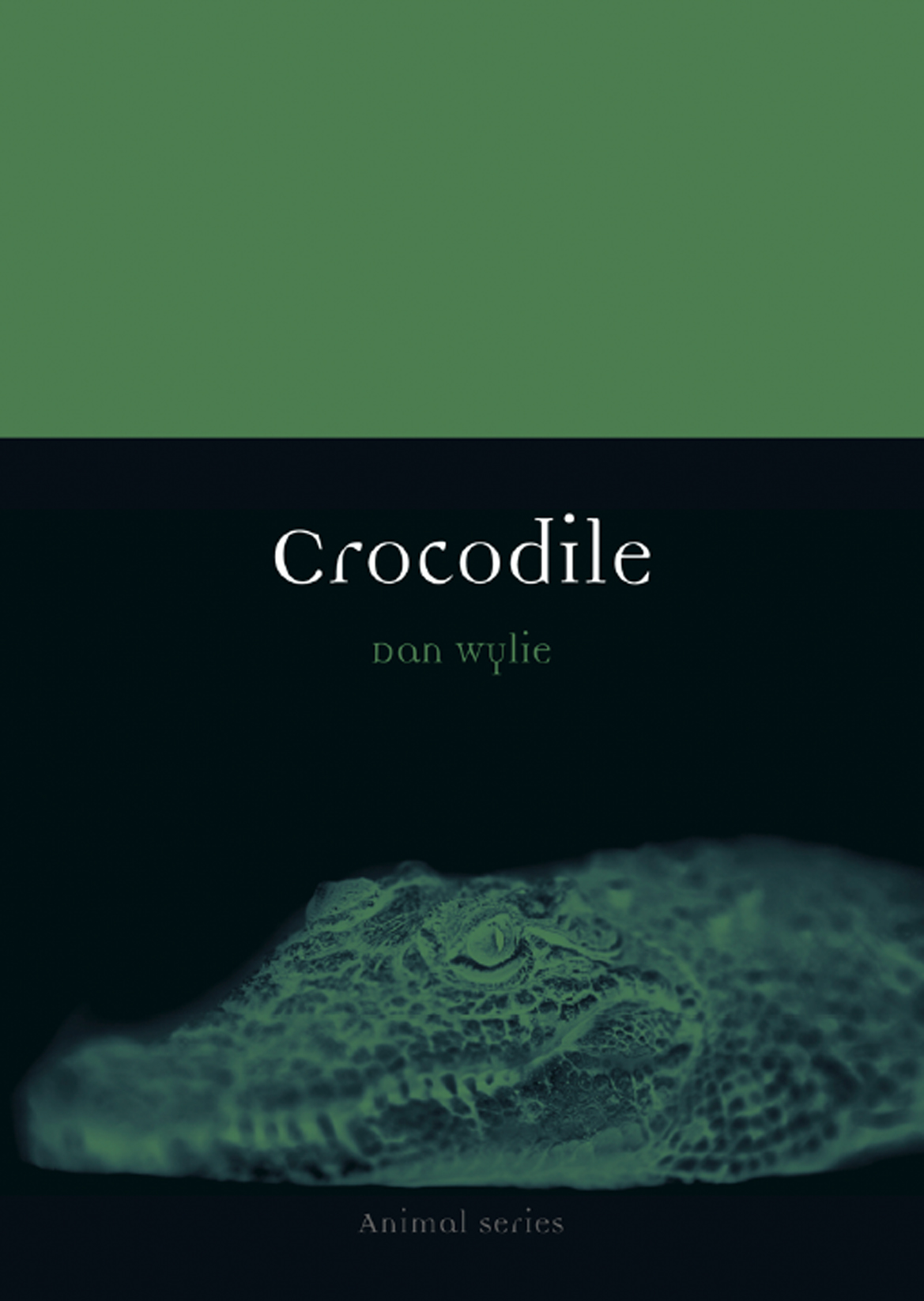

A crocodile farm guide shows the gular flap at the back of the throat.

Some clues can be found in their present-day physiology, so lets begin with the basic crocodilian body. Imagine youre standing on the bank of Rudyard Kiplings great grey-green greasy Limpopo River in Africa, blissfully unaware of impending doom until... you spot, just breaking the waters surface, the bit that shows itself first: the nostrils. Crocodilians smell keenly: a whiff of potential prey in the water can attract them from hundreds of yards away. As the nostrils break the surface, nasal flaps open; air is sucked in with a characteristic sniff. On submersion, the flaps close, preventing flooding of the nasal tubes. These run not into the oral cavity, but further back to a cup-shaped cavity behind the gular flap which seals the throat under water. Oddly, crocodilians lack Jacobsons organ, which in other reptiles detects scent molecules in the mouth itself.

A sharp eye.

Next to appear above the waterline are the raised but retractable lids of cartilage housing the eyes. The crocodilian eye is remarkably sharp, registering some colour. It is slitted like a cats for maximum light-enhancement, helped by an extra layer of cells in the retina, the tapetum lucidum; this is what reflects light back from a torch at night. Do those expressionless eyes really exude tears, as the saying suggests? It is an idea laden with humans projection onto the crocodile of their own vulnerability: attacking so surreptitiously, the crocodile embodies deceit. The pseudonymous compiler Sir John Mandeville in the fourteenth century, uncritically repeating a blend of medieval legend and Aristotle, asserted that cockodrills were like serpents that slay men, and they eat them weeping. The crocodile is, as Edmund Spenser put it in