Billy the Blackfella from Bourke

Billy the Blackfella from Bourke

Edited and transcribed by Chris Woodland

ROSENBERG

First published in Australia in 2015

by Rosenberg Publishing Pty Ltd

PO Box 6125, Dural Delivery Centre NSW 2158

Phone: 61 2 9654 1502

Fax: 61 2 9654 1338

Email:

Web: www.rosenbergpub.com.au

Copyright Chris Woodland 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher in writing.

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Creator: Woodward, Chris, author.

Title: Billy the blackfella from Bourke / Chris Woodward.

ISBN: 9781925078688 (paperback)

ISBN: 9781925078695 (ebook)

ISBN: 9781925078824 (epdf)

Notes: Includes index.

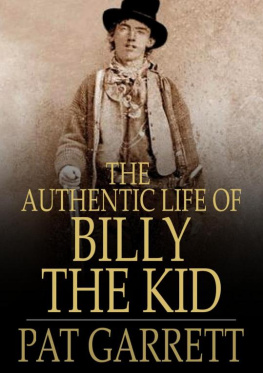

Subjects: Gray, Bill, 1940-2011.

Aboriginal AustraliansNew South WalesBourkeBiography.

DroversAustraliaBiography.

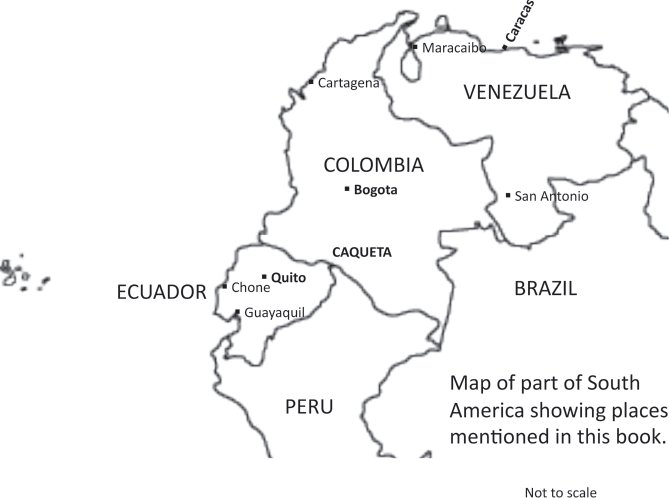

Oil industry workersSouth America-Biography.

Well drillersSouth AmericaBiography.

Bourke (N.S.W.)History.

Dewey Number: 305.89915092

Printed in China by Prolong Press Limited

Contents

Introduction

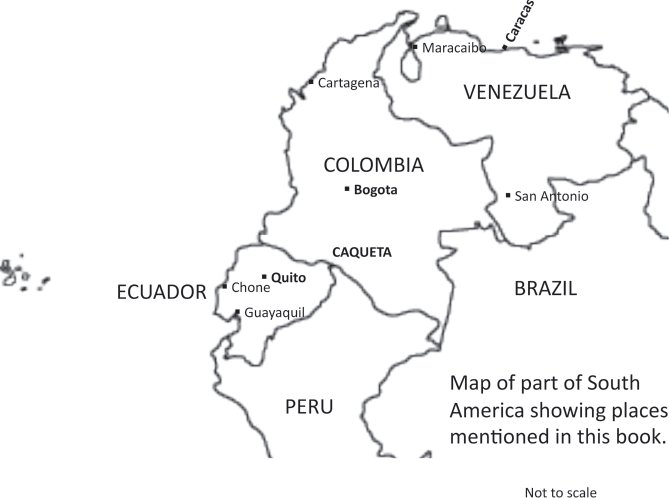

The popular saying that everyone has a story to tell is very true. Every person leads an interesting life reasonably different to others. Billy Gray, the subject of this book, was perhaps noticeably different to most others. His story is one of having been born in an era before his people were considered to be Australian citizens, though some of his ancestors had been resident in this continent before Europe was peopled by modern man; he was a man of limited formal education yet he visited isolated areas of the world, not as a tourist, but as a worker. He had been brought up to know his place: that he was a second-class person, who must remain in the background. In South America he found for the first time in his life that he could move freely without experiencing that feeling of being an outcast; he just blended in.

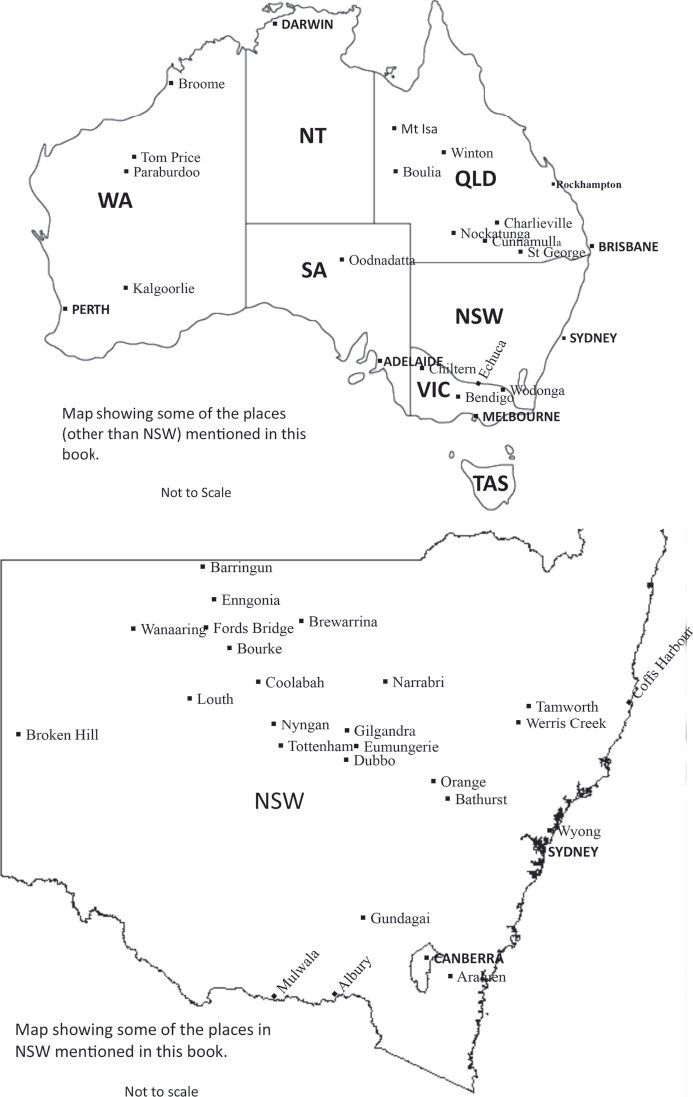

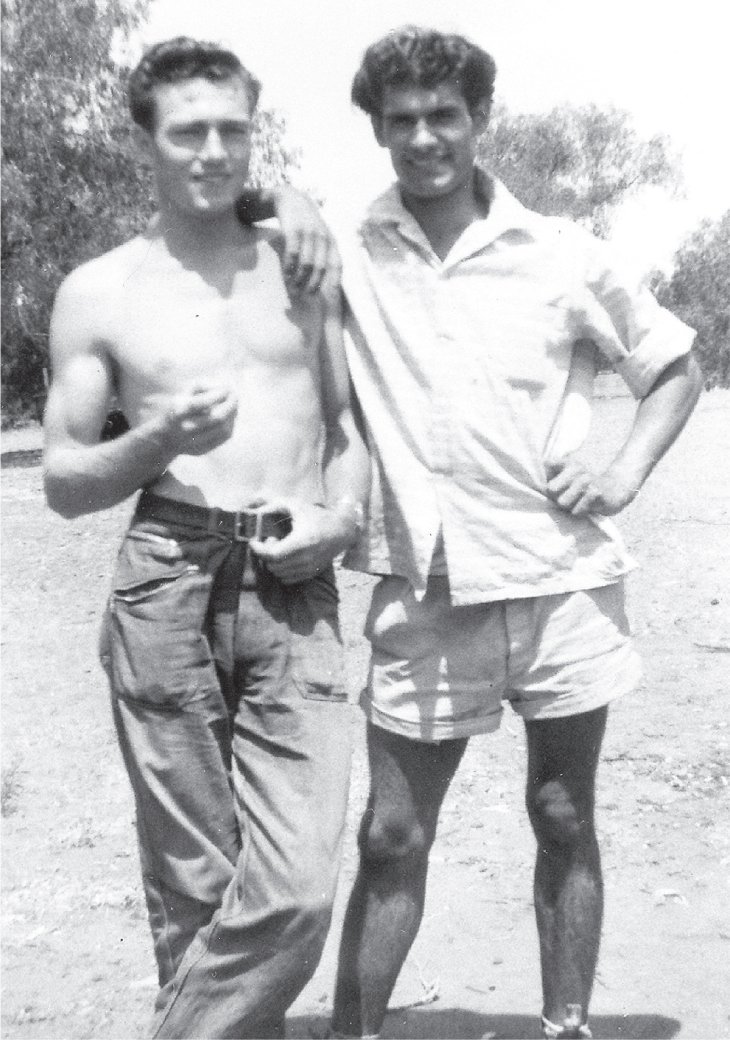

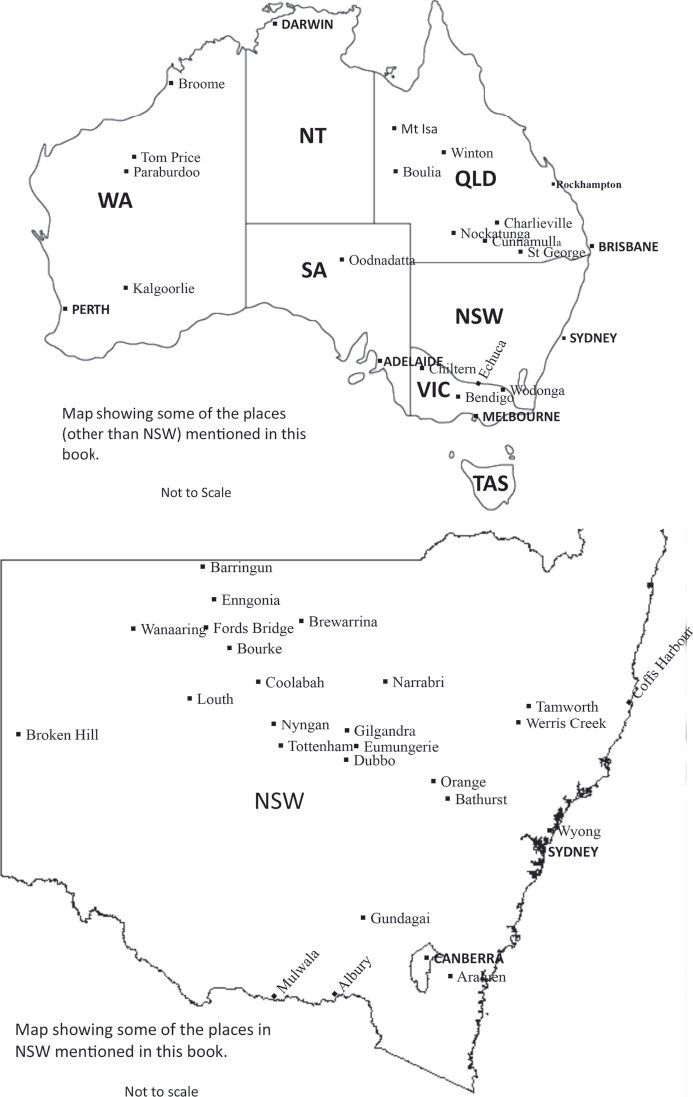

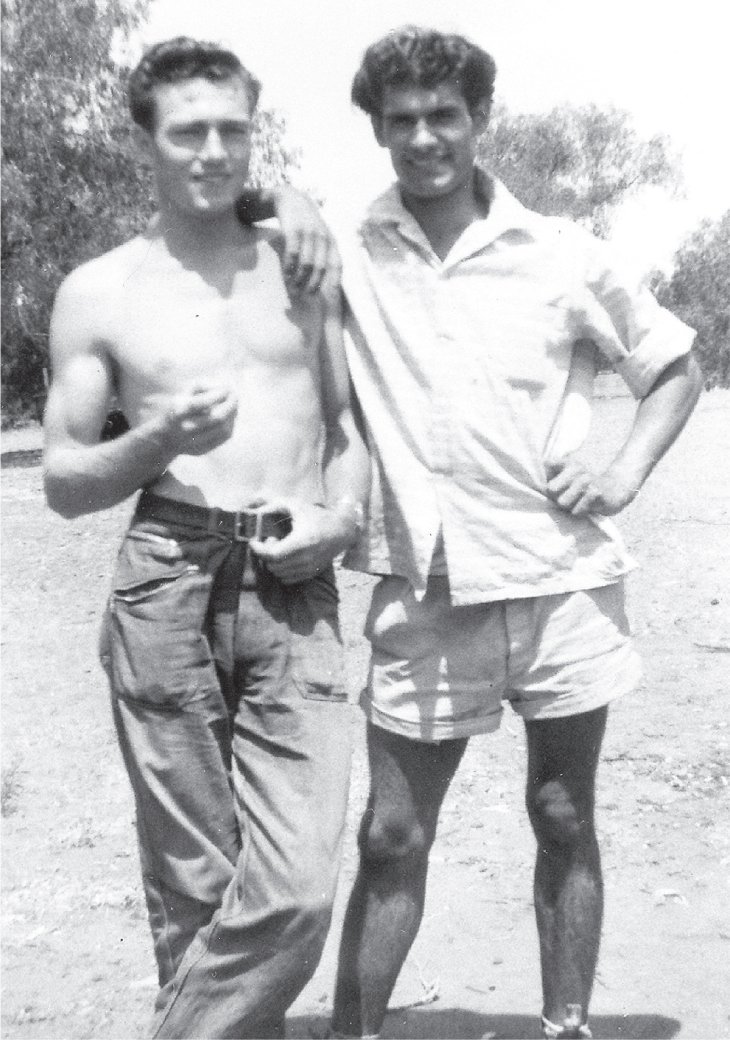

It was January 1959 and very hot when I first met Billy Gray on New Park station. The property extends from the Bourke to Cunnamulla road in Queensland, and runs east along the border on the Queensland side for about 32 kilometres. Though we had a lot in common, no one would have thought that it was the beginning of a close relationship that lasted for 52 years. As young men we both loved singing around the campfire at night, enjoyed tracking down and shooting wild pigs, and had an earnest interest in the bush, its history, what grew in it, the creatures that inhabited it, the tales of the old people about the early days, the drovers and the outback people generally, particularly the original inhabitants. The Aboriginal side of Billys heredity represented the longest continued culture on earth.

Chris Woodland and Billy Gray, New Park station, Barringun, 1959

My interest in the First Australians began when I was an infant at Kempsey on the mid-north coast of New South Wales. No doubt my tolerant and humanitarian parents had a lot to do with my attitude and subsequent fondness for this subject. The first Aboriginal family I was associated with were the Mumblers, who, like many others, came in from Burnt Bridge reserve to do whatever work they could find around the town. My parents had a strong sense of natural justice and were appalled that old Mr Mumbler, who had worked as a police tracker, did not receive a pension when he was retired. Our neighbours across the road in Austral Street would give their indigenous house cleaner all their old clothes, then deduct the value from their paltry earnings.

Later, almost at the age of fifteen, I experienced what was probably the most adventurous episode of my lifetime. My uncle, who had been a Native Affairs officer on Melville Island with the Tiwi people, made it all possible. Following his time on Melville Island, Kevin Woodland had been moved to Darwin. After visiting Sydney he drove my brother and me in his 1940 Buick up to Darwin over roads that would be unimaginable to those of later generations. The lack of decent roads and signposts, the drovers breaks and campfire spotted stock routes, the batwing doors on the outback pubs, the burnt black spots on the bar fronts where the drovers and ringers had positively extinguished their cigarette butts, and all the abandoned army vehicles alongside the welcome bituminised Stuart Highway in the Northern Territory were of another world. It was late 1952 and Darwin Harbour was scattered with bombed ships, the legacy of a war that had finished seven years previously. A few years later the Japanese bought all the wrecks and shipped the scrap iron back to their resource-poor country. In Darwin I met Moreen (also known as Ginger One and Matthias Ulungura) the first Australian to capture a Japanese on Australian soil. This occurred when the Japanese pilot crashed on Melville Island.

Though Kevin was no longer stationed on the island he had organised for my brother and me to stay with his friend Tom Carroll, his wife and young daughter. They were the only white people on the island.

To a bush mad teenager my stay at Snake Bay was beyond my wildest dreams. I would never equal the experiences with tribal people again. It did nothing to allay my interest in the First Australians. Rather, that interest was intensified.

In 1959 Billy was a very handsome, lean and fit young man. His dark hair had a copper tinge to it and he wore a friendly smile showing a good set of teeth.

Each morning before breakfast he would run in the milking cow for the homestead on New Park. The horse paddock was much larger than the 50-acre dairy farm where I spent some of my childhood. Billy had no horse for this and he tracked the milker down through the budda bush and mulga scrub, then ran it back to the yard in his high-heeled riding boots.

Each night around the campfire Billy would play the guitar and sing. I would always sing along and sometimes contribute with the mouth organ. The songs we sang, such as Slim Dustys The Rain Tumbles Down in July and When the Sun Goes Down Outback, related to our own experiences. American Country and Western music was popular also, particularly songs by the well-liked Hank Williams. Later in life Billy became aware of, and besotted with, the Afro-American country music performers such as Charley Pride. It was Billy who taught me my first three guitar chords.

Yarns were also common around the campfire. Billy was an interesting raconteur. His tales, including the one of a heavily pregnant Aboriginal woman having to clamber up on the back of a mail truck while young white men enjoyed seats in the drivers cabin, and stories of the ways and customs of the Old People, always intrigued me.

Music was always an important part of Billys life. Later in Queensland he became involved with a band performing in pubs. First they got Billy up to sing. Then later he also accompanied the group by playing the bass guitar. In his later life it was sad to see him unable to play the guitar, as his hands would not respond because of the hard work theyd endured. By then he relied on cassettes tapes, and then CDs, to address that essential part of his life.

Next page