Copyright 2016 by Jonathan Wilson

Published by Nation Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

116 East 16th Street, 8th Floor

New York, NY 10003

Nation Books is a co-publishing venture of the Nation Institute and Perseus Books.

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address Perseus Books, 250 West 57th Street, 15th Floor, New York, NY 10107.

Books published by Nation Books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at Perseus Books, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail .

Designed by Jack Lenzo

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Wilson, Jonathan, 1976 author.

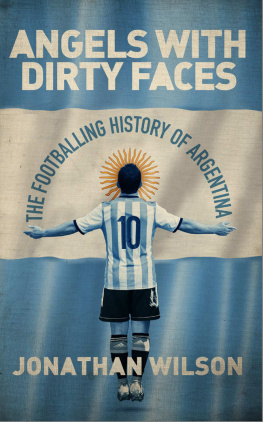

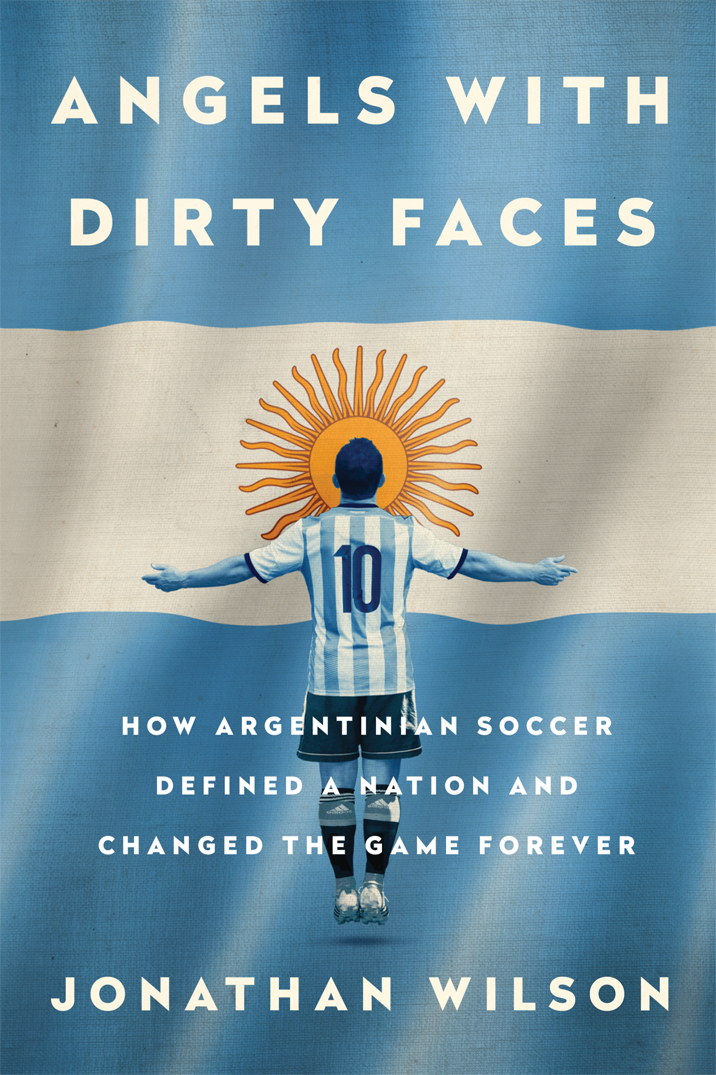

Title: Angels with dirty faces : how Argentinian soccer defined a nation and changed the game forever / Jonathan Wilson.

Description: New York : Nation Books, [2016] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016009501 | ISBN 9781568585529 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: SoccerArgentinaHistory. | Soccer playersArgentina.

Classification: LCC GV944.A7 W55 2016 | DDC 796.3340982dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016009501

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Una cigarrera sahum como una rosa

el desierto. La tarde se haba ahondado en ayeres,

los hombres compartieron un pasado ilusorio.

Slo falt una cosa: la vereda de enfrente.

Jorge Luis Borges,

Fundacin mtica de Buenos Aires

A cigar store perfumed the desert like a rose.

The afternoon had established its yesterdays,

The men shared an illusory past.

Only one thing was missing: the other side of the street.

Table of Contents

Guide

CONTENTS

T he game should never have been in the balance, but it was. Argentina had battered Brazil, had created chance after chance, had had shot after shot, yet it was with only three minutes to go that Humberto Maschio, the tough inside-right from Racing, finally made it 20. In the wave of relief that followed, the Independiente winger Osvaldo Cruz added a third, and Argentina, with a game to spare, were South American champions for 1957, their eleventh title. As the players celebrated on the field after the final whistle in the Estadio Nacional in Lima, a microphone was handed to River Plate defender Federico Vairo so he could address the crowd. Although a leader, he was a player whose gentle face suggested concern most of the time, and on this occasion his emotions overwhelmed him. He tried to compose himself, gripping the microphone more firmly, but when he began to speak, his voice was tremulous. Its..., he said uncertainly, its all thanks to these caras sucias, to these five sinvergenzas. His voice trailed away, and he handed the microphone back to the official whod thrust it at him. He managed only one sentence, but in it he both gave that team the name by which history would know it and encapsulated the spirit of Argentinian soccer to that point.

Nobody had any doubt as to whom Vairo was referring. The forward line of Omar Orestes Corbatta, Humberto Maschio, Antonio Angelillo, Omar Svori, and Osvaldo Cruz had been devastating throughout the tournament, playing skillful, fluent soccer that resonated with a sense of enjoyment. What better name for the five players who had inspired Argentina to the Campeonato Sudamericano than los ngeles con Caras Suciasthe Angels with Dirty Facesa nod to the 1938 film starring James Cagney and Humphrey Bogart and a recognition of both the impudence of their style and the carefree way in which they played, which extended to a less than rigorous attitude toward training. Svori drove [Coach Guillermo] Stbile mad, said left-half ngel Pocho Schandlein. If the bus left at eight for training, Svori was always missing, and hed show up at ten in a taxi. Svori liked to sleep.

In time the Carasuciasas the nickname was abbreviatedcame to stand for the great lost past of the Argentinian game, a golden age in which skill and cheek and fun held sway, before the age of responsibility and negativity. The image of the past may have been romanticized, but the sense of loss when it was gone was real enough, and in that nostalgia for an illusory past when the world was still being made and idealism had not been subjugated by cynicism is written the whole psychodrama of Argentinian soccer, perhaps of Argentina itself.

I n 1535 Don Pedro de Mendoza set off across the Atlantic from Sanlcar de Barrameda, Cdiz, with thirteen ships and two thousand men, having been named governor of New Andalusia by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and king of Spain. Mendoza, and those at the imperial court who granted him half the treasure of any local chief conquered and nine-tenths of any ransom received, dreamed of a land of immense wealth. What he found was a vast prairie populated by hostile tribes whose culture seemed primitive when set against the sophisticated and wealthy empires of Mexico and Peru.

The whole expedition was a fiasco. Mendozas fleet was scattered by a storm off Brazil, and then his lieutenant Juan de Osorio was assassinated; some say Mendoza ordered the murder because he suspected Osorio of disloyalty. Although Mendoza sailed up the Ro de la Plata and, in 1536, founded Buenos Aires on an inlet known as the Riachuelo, any sense of accomplishment was short-lived. Mendoza was confined to bed for long periods by syphilis, while early cooperation with the local Querandes turned to rancor. The three-foot adobe wall that surrounded the settlement was washed away every time it rained, and without the help of the local people, the early settlers struggled to find food and were reduced to eating rats, snakes, and their own boots before finally resorting to cannibalism. As the population dwindled, killed by the indigenous people, illness, or starvation, Mendoza decided to return to Spain to seek assistance from the court. He died on the voyage back across the Atlantic.

Help did finally arrive, but it was insufficient and too late. In 1541 the few survivors of Mendozas mission abandoned Buenos Aires and headed north for Asuncin. They did, though, leave behind seven horses and five mares, which, doubling their population roughly every three years, became an essential factor in the gaucho culture that dominated Argentina three centuries later.

From the very beginning, Argentina, the land of silver, was a myth, an ideal to which the reality could not possibly conform.

I used to live, on and off, in an apartment just off Avenida Pueyrredn, where the district of Recoleta starts to become Palermo. If I turned left out the door and walked past the hospital, carried on for four blocks, past the deli whose owner would loudly lament in English that only Europeans really understood cheese, and then turned right up the hill, Id come to the cemetery where eighteen presidents, writers Leopoldo Lugones and Adolfo Bioy Casares, and Eva Pernperhaps the greatest of all Argentinian mythsare buried.