Contents

Introduction

When you look at what football actually is, in its rawest form, it is initially hard to see how it has been able to become such a politically and financially powerful tool. It is, after all, only a sport that, like rugby, cricket and tennis, can be picked up by just about anyone. Yet football stands alone today as arguably commanding more respect and wielding greater power among ordinary people than many governments.

One hundred and fifty years since the laws of association football were first put down in a form that would still be familiar, at least in passing, to most of us, the game has changed enormously. And yet football retains this universality. Yes, clubs have become increasingly removed from the communities that birthed and sustained them, but still fans pour into grounds, hunch over TV screens, and consume content online like never before. And from the Syrian refugees using breeze blocks as goalposts to the glistening multi-million-pound academies of the worlds top clubs, the game still remains, at heart, the same.

Throughout history, the accessibility and universal a ppeal of football have made it a powerful tool for fighting back against all forms of oppression, from Didier Drogba and his Ivory Coast teammates calling for an end to the civil war back home to Bundesliga clubs joining together against anti-immigration rhetoric, and from players taking a knee against racism to Marcus Rashford challenging the UK government over child food poverty.

It is this side of the game that I love reading about, writing about and exploring: how football can be used as a force for good. As a girl growing up in East London in the early 1990s, I could feel the power of the game on every warm day when, with the balcony windows of my familys council flat open, you could determine the score of the days Arsenal mens match from the cheers that would emanate from the sofas around the estate. A community would be united in celebration, all the ways in which society divides us briefly overlooked.

Later, it would be in those fleeting moments of match-day euphoria that the self-consciousness I felt in being a woman at a football match would fade into the background. That fade was always brief. A look, a comment, being forced to brush past a tightly packed row of men to get to my seat, or a sexist chant that I would pretend to join in with all would quickly remind me that I was different. It is perhaps unsurprising then that womens football is where I have found a home.

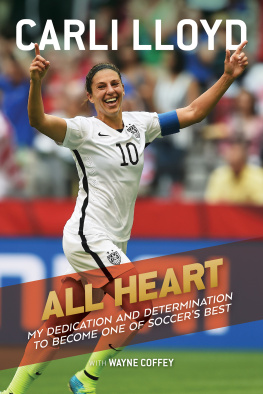

Women are simply one section of society albeit one encompassing half of the global population that has used football, and sport generally, to fight for influence and a more equitable society. Most female players would not say that this campaigning drive is what motivates them to play, or at least isnt why they started playing football. It is not a conscious thing; they are playing football because they enjoy it. But the mere act of playing football is unequivocally a feminist one.

Picking up a ball and heading to a patch of grass violates everything society expects of women how they should look, how they should behave, how they should exercise, what they should wear and, at its core, how they should feel. For too long women have been made to feel like they dont belong in sport. I have seen this repeatedly over the years as I have explored the journeys of players from grassroots to elite, as well as in my own relationship with football.

Growing up, I wanted to be like my dad, wanted to like what he thought was cool. Fortunately, I was blessed with a father who was progressive and embraced and cultivated my love of football. However, he was the exception. In primary school I was the only girl that played football with the boys, the outlier who was shunted into goal, where no one else wanted to play. I wore boys football shirts because girls sizes and cuts did not exist. As I grew and my body changed, the shirts didnt quite fit; they were tighter around the top of the hips and there was no room for a developing bust. It increasingly felt like I was expected to grow out of sport.

My secondary school in Hackney was single-sex, with no boys for me to play against. I felt like I didnt fit in, but I tried to. PE, which seemed to avoid team sports, was universally hated and so I hated it too. For someone who spent the first eleven years of my life refusing dresses and skirts, suddenly I had to pull on a short, pleated skirt and oversized pants to take part. I hated my body, a body that was stopping me from being welcomed in an arena I was so desperate to be a part of. I was self-conscious, I hated changing in front of my peers and I hated my period too. The more I avoided PE and the more I was driven from sport, the more unfit I became and the less welcome I felt.

There were brief moments when I dipped back in. A handful of Arsenal Ladies players came and ran sessions after school for a couple of terms. I held the keepie-uppie record and revelled in those brief evenings dancing across the sports hall with a ball at my feet, but the damage had been done. Friends were bemused that I would stick behind after school, I had to walk home alone in the fading light, I felt unfit and the sessions were fleeting. I stopped. I became a spectator, in the stands where I didnt fit in either. How dare I, a young woman, encroach on this overwhelmingly male safe space?

Times are changing. We live in a wildly different society to the one which existed at the time of the first forays of women into football, a very different society from twenty years ago when I was fourteen and grappling with the emotions discussed above, even. Women can vote, can divorce, can own property, can work, can be single. Yet even today, womens football provokes a vitriolic, misogynist defence of this space that many still consider the preserve of men. Why? Because despite the huge strides forward made by women, ingrained prejudices and oppressive views of a womans place in society are still very much present. That is seen in boardrooms, in pay packets, in advertising, in the need to prevent women from having the right to choose what grows in their bodies, and far, far more.

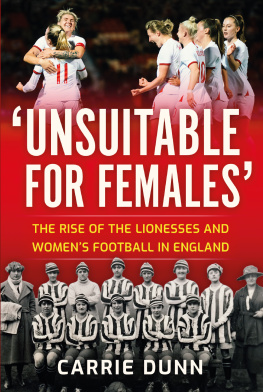

And for some reason, the very idea of a woman pushing back against the system holding her down by entering a place of escapism for men has always been a step too far for some. The first recorded official womens football match took place on 9 May 1881 between Scotland and England at Easter Road in Edinburgh, and the disdain from the press and public was palpable. Contempt for clothing, the standard of play and appearance dominated. Oh, how times have changed. Yet goalkeeper Helen Matthews (also known as Mrs Graham) persevered, and the game she organised saw the host nation finish victorious with a 30 win. Five days later, in front of 5,000 fans, a second game was abandoned after hundreds of men mobbed the pitch, forcing the players to flee on a horse-drawn bus.

Through more than a century of setbacks, bans and prejudices since, the resilient womens game has climbed off its knees time and time again. It has been fought for by women who could have easily given up or swapped into a sport more palatable to wider society. It has been driven both by those that desire change on a political and societal level but also by those who just enjoy the freedom of playing the game. Now, finally, womens football is seeing the investment and support it has been so lacking for so long. And yet, despite the ideological battles for womens right to play being won, it still gets attacked like no other sport. The trolls come out in force: