Yijie Zhuang - 24 Hours in Ancient China

Here you can read online Yijie Zhuang - 24 Hours in Ancient China full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Michael OMara, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:24 Hours in Ancient China

- Author:

- Publisher:Michael OMara

- Genre:

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

24 Hours in Ancient China: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "24 Hours in Ancient China" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

24 Hours in Ancient China — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "24 Hours in Ancient China" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

First published in Great Britain in 2020 by

Michael OMara Books Limited

9 Lion Yard

Tremadoc Road

London SW4 7NQ

Copyright Yijie Zhuang 2020

All rights reserved. You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-78929-121-6 in hardback print format

ISBN: 978-1-78929-123-0 in ebook format

Cover design and illustrations by Patrick Knowles

www.mombooks.com

Contents

T he era of the Western Han is one of the most fascinating periods in all of Chinas long and colourful history. It is a period of dynamism and change political, social and technological an era in which population growth soared, new ideas were explored and society endured wrenching tensions as the old order clashed with new ideas.

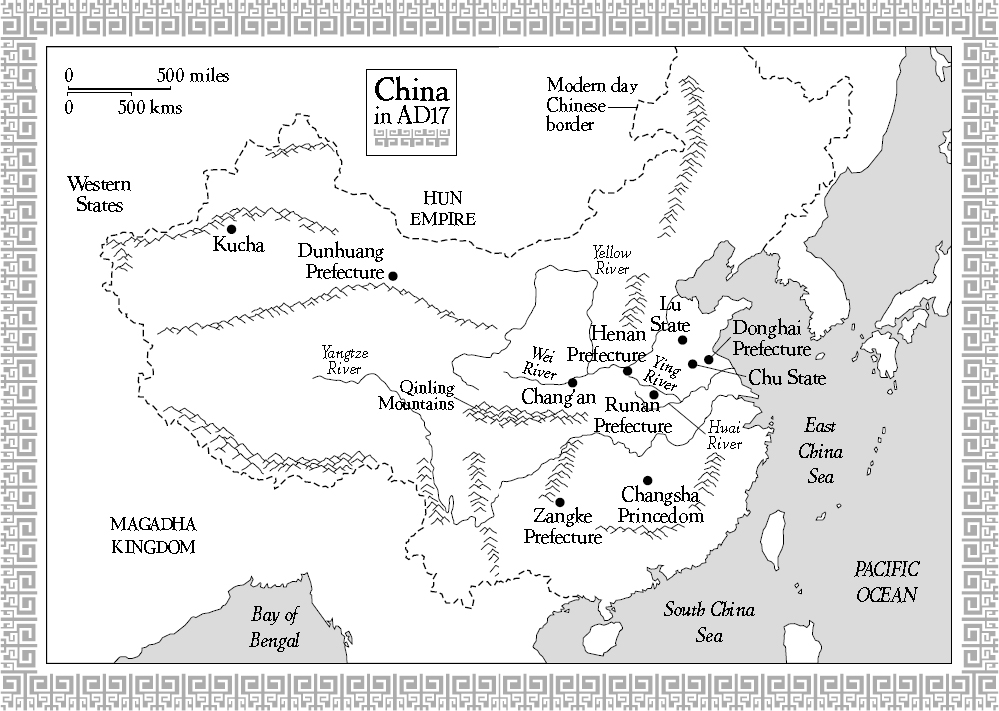

The Western Han is the imperial dynasty that has given its name to this era. Western is used to distinguish this dynasty from the later Eastern Han dynasty that followed between AD 25220. By European dating, the Western Han emperors came to power in 202 BC and their rule endured for centuries thereafter, with the rise of their empires territory, political stability and economic progress mirroring that of the Roman empire on the other side of the Eurasian landmass.

The dynasty was founded by Liu Bang, an ambitious warlord who overthrew the short-lived Qin dynasty in a savage civil war, but the empire only really started to flourish with the reign of the Emperor Wu (14187 BC). The early Western Han emperors before Emperor Wu followed the Daoist philosophy of governance by doing nothing a policy of benign neglect that allowed the population to recover from the economic devastation of war and Qin misgovernment. Emperor Wu changed this policy and used the political capital gained from a series of successful military campaigns to entrench Confucian ideas into government and society, as well as initiating the Han tradition of large-scale infrastructure projects.

This book is set in AD 17, when the effects of Emperor Wus policies have brought Chinese society to a prolonged economic and cultural apogee. Epitomizing the era is the current emperor Wang Mang, himself a usurper and a reformer in an age that was both vibrant and innovative but also riven with conflict and contradictions. In the book we see some of these social conflicts as they begin to develop (eventually becoming a tidal wave of popular unrest that climaxed in AD 23 when a rebellious mob invaded the imperial palace and killed Wang Mang).

After the fall of Wang Mang the population went into steep decline through war, famine and flooding, and it took centuries to again reach the number of 60 million souls living and working just before Wang Mangs reign in AD 2.

Today, we know a great deal about the Western Han aristocracy through contemporary texts and archaeological research. Palace ruins, the still-standing remnants of city walls and military bases, together with the remains of extravagant imperial mausoleums provide vivid snapshots into the luxurious life of the Han elite. While scholars and scribes wrote extensively about the follies and excesses of their wealthy and pampered masters, their texts have given us very little material with which to establish a clear picture of the lives of the ordinary people who lived in this extraordinary time.

That they were much better off than their forebears from earlier eras is undoubted. Agricultural production increased steadily under the rule of the Western Han. Wheat, together with millets, gradually became the primary crop of the empire, pushing yields to a new height. Ordinary households benefited from the invention of numerous agricultural technologies such as Daitianfa (rotational farming), animal-draught ploughing, and the widespread application of improved iron agricultural tools. The Western Han also enjoyed an unprecedented level of craft production, which included lacquer wares, ceramics, bronzes, iron objects, and many other elaborate goods. An increasing proportion of the population was drawn into these burgeoning industries and shared in the wealth that they created.

Economic success had a profound impact on the ideology of the era. From emperor to commoners, the eternality of afterlife became deeply rooted in their minds. While the emperors and elites squandered massive resources to build extravagant mausoleums, wealthy commoners could also build luxurious tombs for themselves. That three of the chapters in this book feature a tomb builder, a tomb robber and a mausoleum minder is a reflection of the importance of death and the afterlife in contemporary Han culture.

Recently, archaeological projects have started to shed light on the forgotten lives of the common people of this era. Among the most remarkable discoveries is the farming compound of Sanyangzhuang buried for centuries beneath layers of mud from the Yellow River floods. There is also the town site recently found in Quxian, with streets, kilns, wells and many other everyday features telling how ordinary people lived. The Laoguanshan Han tomb in Chengdu has yielded some of the earliest medical records and also well-preserved looms, while other finds across the country include numerous mural paintings, bamboo and wooden slips, and ceramic models. These objects bear invaluable witness to the family life, working conditions and deaths of ordinary people of the era, not only in the centre, but also at the frontiers of the empire.

24 Hours in Ancient China brings the everyday ancient Chinese Han citizens vividly to life, combining information from the latest archaeological records and research with traditional historical documents. Where the data permits, the book highlights and dramatizes the social tension between governor and the governed, employer and employee, and wife and husband. We see that even in a time of innovation and plenty, resentment towards a harsh and arbitrary government was combined with a perception that a wealthy few had stolen the benefits of prosperity a formula that was to lead inexorably to revolution.

As with the other published titles in this series, 24 Hours in Ancient China offers stories of twenty-four individuals from different professions and positions in society. Compared to ancient Rome, Athens and Egypt, ancient Han is relatively less well known to the western audience. The selected stories aim to give the reader a feel for the rich tapestry of social and economic life while the empire was at its peak.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «24 Hours in Ancient China»

Look at similar books to 24 Hours in Ancient China. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book 24 Hours in Ancient China and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.