An imprint of Rowman & Littlefield

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

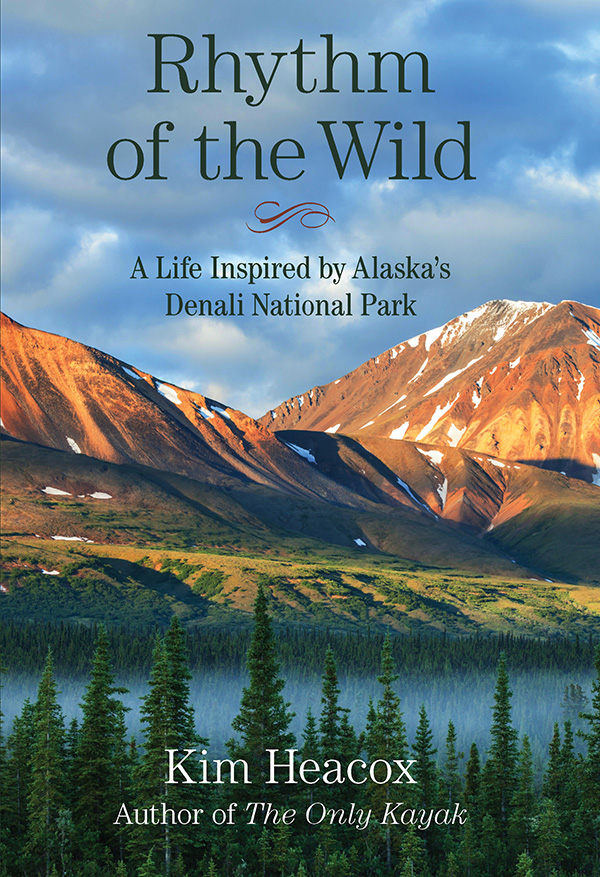

Copyright 2015 by Kim Heacox

Small portions of this book appeared previously in National Service literature about Denali National Park.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available

ISBN 978-1-4930-0389-1 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-1-4930-1665-5 (ebook)

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

For my brothers, Mick and Bill, the colonel and professor, who, when I graduated from high school, gave me a hardcover American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language

Wilderness, the word itself is music.

EDWARD ABBEY

Contents

Prologue

The River Has Been Here for Ten Thousand Years

Chapter One

The Midnight Ride of Kimmy the Kid

Chapter Two

Red Socks and Secretary Watt

Chapter Three

Not Recommended for Rehire

Chapter Four

The Presence of Absence

Chapter Five

Alexander Supertramp

Chapter Six

Kantishna Gold and Usibelli Coal

Chapter Seven

One Degree North of Heaven

Chapter Eight

The Bear Is Nowhere and Everywhere

Chapter Nine

The Battle below Mount Galen

Chapter Ten

Wolfing Down Pizza

Chapter Eleven

The Grasshopper Effect

Chapter Twelve

Hiking with Melanie

Epilogue

My Inner Porcupine

Authors Note

As the arc of this story covers nearly thirty-five years, and some memories remain clearer than others, Ive taken a novelists license to reconstruct the spirit of certain events and conversations as best I could.

Prologue

The River Has Been Here for Ten Thousand Years

I AWAKEN, and for an instant, socked deep in my sleeping bag, I have no idea where I am. Then it comes to me... and I smile.

Melanie sits up and zips open the tent.

Kimmy, Kimmy, Kimmy, she says, its here. Look. Its out.

I rise onto my elbow and there it is, blushed pink above the clouds, floating, as if it arrived only minutes ago, late for its own show. The summit of Denali, eighteen thousand feet above our campsite, the highest mountain in North America.

I pull out my journal and write... nothing.

There it is, Melanie says again, trying to convince herself of its improbable size and beauty and height. Always higher than expected. Right there. Right here .

All morning we stand outside our tent and sip tea and watch the great mountain undress, cloud by cloud, playful one moment, shy the next. I shiver against the September chill. Camping is not as easy at age sixty as it was at age six, back in Spokane. But Im not complaining. Its good to be here; its great to be here.

Melanie and I have a site at Wonder Lake Campground, in the middle of Denali National Park, near the end of the park road. Other campers stand in admiration, their tents sprinkled across the autumn-burnished tundra. They speak in English, German, French, Spanish, Korean, Japanese, Chinese; their voices animated, sweetened with laughter, old people and young, grateful in this place we call Nature. Not a bad deal, this Denali. Wild country in every direction, a university of the far north, a holy place, of sorts, a cathedral without walls, made of the earth itself, no improvements needed. Sky blue and black; spokes of silver light. Who needs stained glass when you have a clearing storm? Who needs flying buttresses when you have sandhill cranes?

After a week of hard rain, this is our reward.

I hear a guitar, somebody fingerpicking. A Beatles tune? Bob Dylan? Fleetwood Mac? I cant tell. What I can tell is this: the guitar fits. The notes float like leaves on water, as if Denali National Park were a work in progress, an unfinished symphony waiting for our most delicate gestures of accompaniment.

Later, when sandhill cranes fly overhead once more, fluting their ancient music, the guitar stops. Everybody stops. And once the cranes are gone, the guitar resumes, softly. This time I recognize it. A John Lennon song: Across the Universe.

YEARS AGO in a cowboy cafe in Moab, Utah, I met a nine-fingered guitarist who poured Tabasco on his scrambled eggs and told me matter-of-factly that Utah was nice, Montana too. And of course, Colorado. But any serious student of spirituality and the American landscape must one day address his relationship with Alaska, and once in Alaska, he must confront Denali, the heart of the state, the state of the heart.

Spirituality and landscape, I thought. What kind of double major is that?

By Denali he meant both the mountain and the national park. Each complements the other. One is the highest mountain in North America; more massif than solitary peak, a granitic seductress white with snow and ice, so high and imposing that it veils itself in weather of its own making, and by slow degrees or sudden boldness, it appears. And when it does, people fall silent, lost in deep regard.

The other Denali is a six-million-acre national park and preserve, the worlds most accessible subarctic sanctuary, nearly three times the size of Yellowstone, more than twice as close to the North Pole as it is to the Equator, a vast ice age stage of glaciers, rivers, tundra, and taiga. From its mountain centerpiece the park runs in every direction as an ocean of land, storm-tossed yet still, silent yet alive . It is fetching in all seasons, in every dress, where winter sets down cold as iron, spring is a brittle wind, summer a short, exuberant breath, and autumn a splash of crimson and gold.

Add to that the wildlife. Gyrfalcons and grizzly bears, Lapland longspurs and lynx. Marmots, merlins, and moose. Great braided rivers, blizzards of blueberries, and constellations of wildflowers, Dall sheep and wolves, things near and far, seen and unseen, as if we had witnessedor dreamed of witnessingthe making of something wondrous, wild, and profound, a reinvention of the beginning, and ourselves in that beginning.

Nine Fingers was right. I see that now as I consider the chiseled mountains and rounded hills, the tendrils of willow among dwarf birch, the glacial-fed rivers shining in the sun, the clouds dashing about the ever-changing sky, the trees solemn and serene, keeping their opinions to themselves yet offering wise counsel whenever we listen.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.