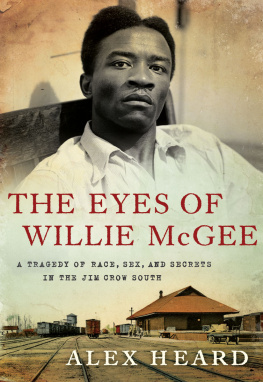

Dead in the night.

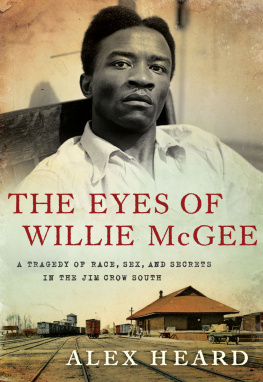

O n May 8, 1951, a thirty-five-year-old African American named Willie McGee was electrocuted in Laurel, Mississippi, on a much-disputed charge that he raped a white housewife named Willette Hawkins. A few days later Eleanor Roosevelt, who was traveling in Europe, received a protest letter about the execution, sent by a Swiss citizen who identified himself as Mr. F. Aegerter.

Aegerter didnt know Roosevelt and she didnt know him. But he knew she was in Geneva for a meeting of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights, so he took a moment to sound off about the human rights of Willie McGee, a man whose death he deeply mourned. During a legal battle that lasted more than five years, McGees story had risen from obscurity to fame, and Aegerter, who probably read about McGee in French-language newspapers, felt certain he was innocent. As he knew, the former First Lady had avoided taking part in a widely publicized campaign to stop the execution. He wanted to know why.

Roosevelt didnt apologize. Just the opposite, she pushed back. In a reply written on the 18th, she told Aegerter she was very familiar with the facts of the McGee sagaunlike him. [Y]ou do not seem to have much understanding of the case about which you write, she informed him coolly. It is quite true that all of us oppose a law which is applied differently to white and colored and that happens to still be in effect in some southern states.

In the case of Willie McGee, while I regret there should be this discrimination in the law, I have to add that he was a bad character and so was the white woman, so there was very little that one could feel personally about.

That sounded definite, as if she had inside information. But the truth was that Roosevelt knew very little about McGee or the white woman. A lot of what she thought she knewand this was true for Aegerter as wellwas rumor mixed with fact, unproven allegations, or simply wrong, since the story produced more than its share of inaccurate reporting, lies, and colorful but useless folklore.

The bad character phrase makes it clear shed heard about and believed the most explosive allegation of all: McGees claim that his sexual encounter with Willette wasnt a rape but an act of consensual sex, part of a long-standing love affair that she had instigated. As for Roosevelts observation that the story lacked elements that could stir the soul, she couldnt have been more off base, because Aegerter wasnt the only person who cared. By 1951, hundreds of thousands of people knew McGees name and what it represented, and many had passionate opinions about what had happened to him inside Mississippi courtrooms.

The story began in November 1945, when McGee, a longtime Laurel resident who worked as the driver of a wholesale grocery-delivery truck, was charged with breaking into a home in a middle-class white neighborhood and raping Mrs. Troy Hawkins, a thirty-two-year-old housewife and mother of three.

The rape allegedly happened in the predawn hours of November 2, a warm autumn Friday. As the still-traumatized Mrs. Hawkins told police after daybreak that morning, she was asleep in a front bedroom with a sick twenty-month-old girl at her side. Her thirty-seven-year-old husband was in a room near the back of the house, having gone there after spending several hours helping Willette take care of the child. She said she woke up and heard a man crawling toward her on the floor. In an instant, he was on top of her, smelling like whiskey and threatening to kill her and the child if she didnt shut up and submit. Once he was done, he told her never to say a word about what happened or he would come back and kill her. Then he ran out the front door. Mrs. Hawkins said it was too dark to see the rapists face, but she knew he was black by the texture of his hair.

McGee became a suspect in part because he didnt show up for work on Friday, but also because Laurel police found witnessesincluding two male friends of hiswhose statements seemed to place him in the vicinity at the time of the assault. He was arrested the next day in a nearby city, Hattiesburg, briefly taken back to Laurel, and then driven to jail ninety miles away in Jackson, the state capital. Jackson was home to a massive county courthouse with a two-floor, upper-story lockup that was considered safe from attacks by lynch mobs. Often in cases like this, black defendants were whisked away from wherever theyd been arrested and taken straight to the Hinds County jail.

The trial was held in early December, amid so much local hostility that the governor of Mississippi sent McGee back to Laurel under heavily armed guard. It lasted only a day, with an all-white jury sentencing him to death after deliberating for less than three minutes. There would be two more circuit-court trialsthe first two verdicts were reversed on procedural grounds by the Mississippi Supreme Courtfollowed by a three-year period of state and federal appeals, including multiple appeals to the U.S. Supreme Court.

For a long timethrough all three trials, in factthe McGee case was barely noticed outside Mississippi, but by the end that had changed dramatically. People all over the United States, Canada, South America, Europe, and Asia had read or heard about his death sentence and were convinced he was either the victim of a racist frame-up or, if guilty, had been condemned unfairly, since Mississippis death penalty for rape was only applied to blacks, never to whites. In 1950 and 1951, thousands of individuals sent letters, postcards, and telegrams to public officials who had the authority to halt the executionincluding Mississippis governor and chief justice, the justices on the U.S. Supreme Court, and President Harry S. Trumandemanding either a new trial, a prison term instead of death, or outright clemency. A week before the execution, Truman even heard from McGees children, who pleaded with him in a letter to save their father.

Dear Mr. President,

We are writing to you about our daddy Willie McGee who have been in jail five years and on May eight they are going to put our daddy on the hot seat. Will you please not let him die, Mr. Truman. You is our president.

My name is Gracie Lee McGee. I have two sisters and one brother. My poor mother is somewhere trying to get my daddy home. She may come by your house. Please help her.

Like F. Aegerter, most people who spoke out werent public figures, but several wereor soon would be. McGees lead defense attorney during the appeals was Bella Abzug, a young labor lawyer from New York who was destined for fame in the 1960s and 1970s as a feminist and politician. Long before that, the McGee case put her in the national spotlight for the first time. In March 1951, William Faulkner, the recent recipient of the Nobel Prize for Literature, signed off on a press release that said that McGee was probably innocent and should be spared. In April, Albert Einstein issued a statement in which he asserted, with utmost confidence, that any unprejudiced human being must find it difficult to believe that this man really committed the rape of which he has been accused. Moreover, the punishment must appear unnaturally harsh to anyone with any sense of justice.

There was a lot more besidessupport from people like Paul Robeson, Josephine Baker, Jessica Mitford, Norman Mailer, Richard Wright, and Frida Kahlo, along with protests from labor unions, political groups, and foreign governments. As McGees last day approached, the U.S. State Department sent a staffer to monitor the case in Jackson because many foreign embassies, prompted by inquiries from citizens back home, were demanding to know why Mississippi seemed determined to kill an innocent man. By the end, news organizations all over the worldincluding the New York Times , the Washington Post , Time , Life , Newsweek , the Nation , and newspapers overseaswere covering McGee intensively. The day after his electrocution, the French paper Combat spoke for many when it declared that the Mississippi executioner has won out over the world conscienceYesterday morning a little of the liberty of all men and a little of the solidarity between the peoples died with Willie McGee.