Table of Contents

For my mother and in memory of Sylvia Jubber

Preface

In June 2009, President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad of Iran was re-elected by a landslide.

Or, to put it another way: in June 2009, hundreds of thousands of people marched through the streets of Tehran, demanding a recount.

This, after all, is the land where there are always two sides to the story.

As usually happens in Iranian history, the demonstrators were suppressed: knocked down with chains and batons, pepper spray and gunfire, carted off in SUVs, and in some cases tortured or killed.

And, as usually happens in Iranian history, they found subtler, more secretive ways of expressing their outrage. They voiced their opinions on social networking Web sites and uploaded protest songs. They released green balloons from their rooftops, declaring their support for the defeated candidate, Mir Hossain Mousavi, who had chosen greenthe color of Islamas his emblem. And one day they gathered in large numbers in downtown Tehran around the statue of a medieval poet and tied a green scarf around his neck.

That poet was Ferdowsi, whose Shahnameh, or Book of Kings (an epic completed 999 years before the demonstrations), tells of the many rulers who, like President Ahmadinejad, dismissed their opponents as dirt and dustand usually wound up as the victims of a coup or a popular uprising.

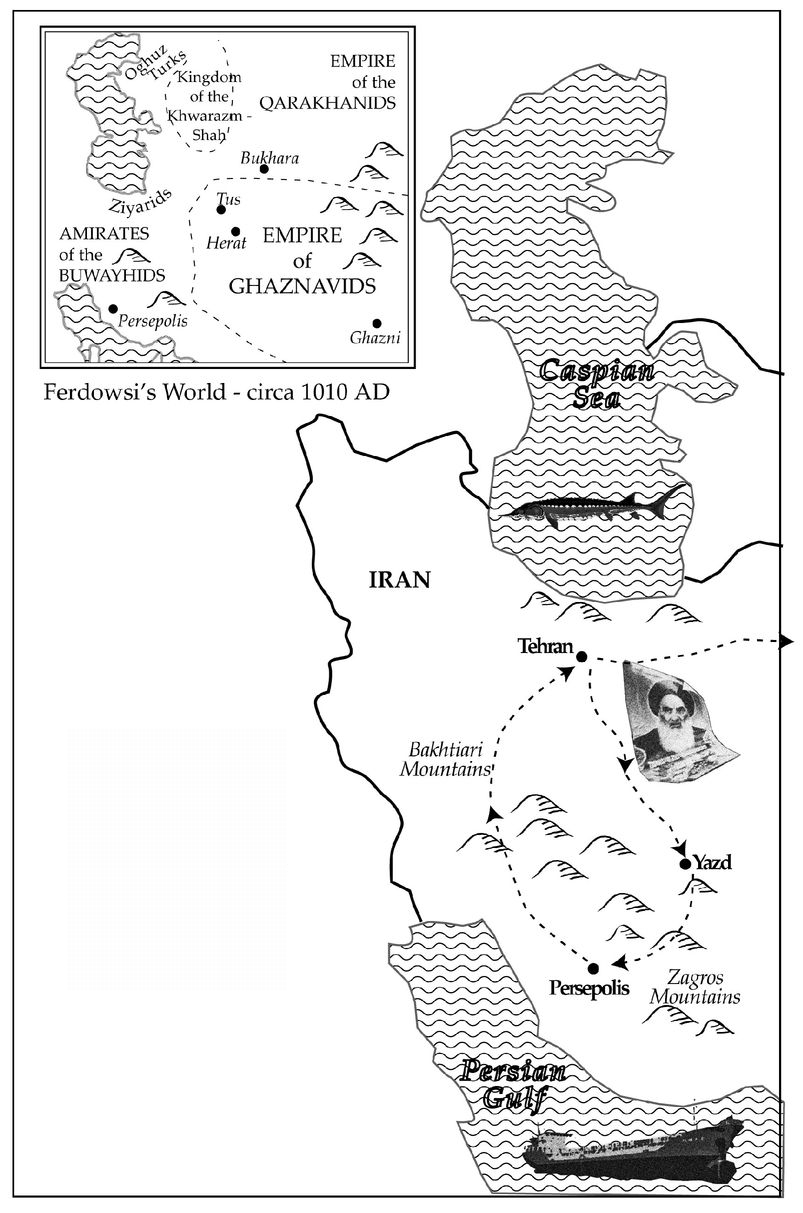

This is the story of my journey in Ferdowsis world, both past and present, a few years before the protests broke out. It was a time when the presidency was passing from the ineffectual Mohammed Khatami to the volatile Ahmadinejad; when across the border Afghanistan was dipping its toes, hesitantly, in a new democracy; while in neighboring Turkmenistan the worlds oddest dictator was nearing his last breath.

In the summer of 2009, images of the demonstrations would burst onto news screens around the world. But they were hardly new. Iranians had been protesting for much of the past decade. And, as the statue in the green scarf in downtown Tehran quietly underlines, their leaders had been abusing them for longer.

IRAN & CENTRAL ASIA TODAY

Tavana buvad har ki dana buvadAll who had power had knowledge

WRITTEN ON THE GATE OF TEHRAN UNIVERSITY, FROM FERDOWSIS SHAHNAMEH

Prologue

Mashhad, Eastern Iran. September.

Oh. My. God.

One glimpse is enough to rip out my optimismlike someone came along and extracted it with a knife.

The bus is the last in its row, each more battered and less brightly painted than the one before, its roof more heavily crushed by boxes and buckets strapped on with string, and a larger pool of water rising around the wheels to trap them in a glue of mud. All the buses in the station look decrepit, but this one is a parody of the rest. It looks like the worst bus in the world.

A man is standing over me, wrinkling his nose at my ticket. It turns out hes the driver.

Why do you go to Afghanistan? he exclaims. You think this is a country for tourists?

His laugh is throaty and thoroughly disconcerting. Had the old man behind me not set his arm on my shoulder, I might be making a dash for the bus back to Tehran.

I am a traveler like you, he whispers.

This man has skin like walnut bark and wears a gray waistcoat over his knee-length shirt, under a brimless woolen cap that looks like its been woven from his beard.

I have been on a pilgrimage, he continues, to the Holy City.

You are a Hajji? Youve just come back?

No, no, no! His teeth gleam gold between his parched lips. I went thirty years ago. I couldnt afford to go now!

His small gray eyes shine through the creases of his skin. He seems to be kind, so I decide to stick with him.

Afghanistan is a good country, he says, poking his nose between the headrests in front of mewe have settled inside the bus now. He squinnies his brow for a moment, before adding, It was a good country.

When? says a man in an ocean-colored polo shirt whos taken the seat across the aisle from mine. He looks like he should be on vacation in Hawaii.

The Hajji looks up, frowning, then in a burst of inspiration he declares, In Kaiser Wilhelms day! He raps the headrest as he explains, There was a train.

We wait an hour for movement. When it finally comes, there is a terrible groan underneath us, as if some wild beast has been stretched out under the chassis, then a tick-tick as the engine rattles to a stop. Is this bus not even capable of forward propulsion? But I can hear a noise swelling around us, suggesting another cause for our pause. Gingerly, the Hajji lifts a pleated nylon curtain to peer through the window. I notice an anxious expression creeping across his face.

Mujahideen, he whispers.

A wave of sunlight washes through the door: a swamp of flailing limbs, enormous beards, long torn gowns. Boxes fly down the aisle; burlap sacks pile on the seats and around the steps in the middle. Buckets clatter on top of them, all the way up to the Formica ceiling, as do more sacks, plastic bags, and finallyshunted through the door, defying the tiny space thats lefta Honda motorcycle.

They are fighting men, whispers the Hajji. Do not say you are a foreigner.

All of them are dressed in baggy trousers and knee-length shirtsthe traditional Afghan costume known as shalwar qameez. I bought a set for myself only yesterday, knowing I would need it in Afghanistans troubled south, but I havent put it on yet, so it will be easy to identify me as an outsider. Hiding my tell-tale Roman-scripted notebook in the overhead rack, I excavate an enormous green-jacketed hardback out of my pack. Its the only Persian book in my possessionthe language not only of the Iranians whom Im leaving, but also of a large number of the Afghans among whom Ill be traveling. Tooled across its spinea gorgeous cluster of golden dots, elaborate curls, and long barbed stalksis the word ShahnamehBook of Kings.

You are reading that? asks the Hajji, his gold teeth flashing in his gasp.

The man in the ocean-colored polo shirt, whose name is Wahid, is more proactive.

Here, he says, leaning across the aisle and reaching for the book, give it here.

He turns its pages delicately, and familiarlyas if hes caressed these very pages in the pastand when he comes across a verse he likes, his mouth expands to the size of a tea saucer:

| Mayaazaar muri ke daneh kash ast | Oh stamp not the ant that is under your feet |

| Ke jaan daarad u jaan e shirin khush ast. | For it has a soul and its own soul is sweet. |

The Hajji smiles, his eyes as bright as his gold teeth, repeating the verse in a whisper, as if to memorize it for himself. I have come across plenty of poetry aficionados in Iranon a few occasions Ive even attended poetry circles where traditional instruments were played as people recited from their favorite authors. But I was advised not to expect this sort of thing in Afghanistan. They are murdering brutes was one of the less cryptic descriptions I heard. So to watch polo-shirt-wearing Wahid, his eyes glued to the pages and his lips quivering to the rhythm of the thousand-year-old words, is hugely reassuring. Maybe the Afghans wont be as formidable as Ive been warned.