About the Author

Nicholas Jubber moved to Jerusalem after graduating from Oxford University. Hed been working for two weeks when the intifada broke out and he started travelling the Middle East and East Africa. He has written three previous books, The Timbuktu School for Nomads, The Prester Quest (winner of the Dolman Prize) and Drinking Arak Off an Ayatollahs Beard (shortlisted for the Dolman Prize). He has written for the Guardian, Observer and the Globe and Mail.

Also by Nicholas Jubber

The Prester Quest

Drinking Arak Off an Ayatollahs Beard

The Timbuktu School for Nomads

First published in Great Britain in 2019 by John Murray (Publishers)

An Hachette UK Company

First published in the United States of America by Nicholas Brealey Publishing

An imprint of John Murray Press

An Hachette UK Company

Copyright Nicholas Jubber 2019

The right of Nicholas Jubber to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988.

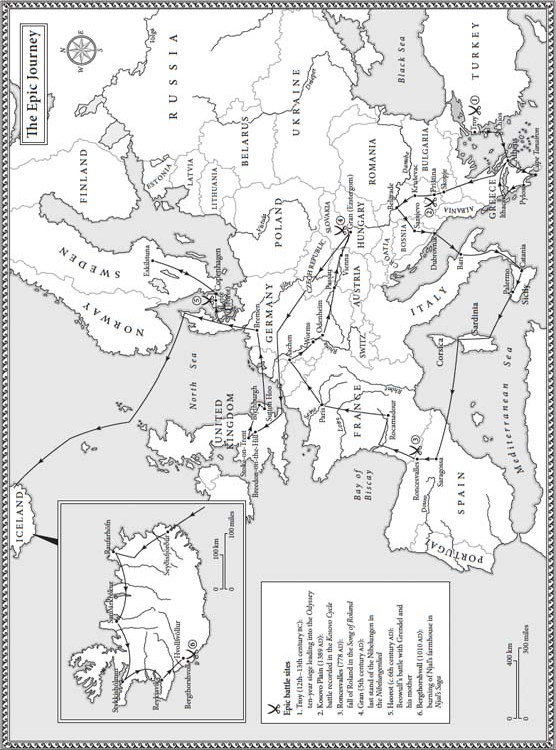

Internal artwork by Rodney Paull

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

UK ISBN 978-1-47366-574-3

US ISBN 978-1-47369-525-2

www.johnmurray.co.uk

www.nbuspublishing.com

For Milo and Rafe

Contents

Timeline

Some of the dates that follow are speculative.

| 1188 BC | Troy is sacked by the Greeks and Odysseus sails back towards Ithaca |

| 1178 BC | Odysseus returns to Ithaca |

| 8th century BC | The Odyssey is composed |

| AD 437 | The Burgundian Kingdom is sacked and King Gunther is killed (see The Nibelungenlied ) |

| AD 451 | Burgundian troops fight against Attila the Hun |

| AD 516 | Hygelac, chief of the Geats (and Beowulfs overlord), falls in a raid against the Frisians |

| AD 778 | Roland dies in an ambush at Roncesvalles |

| AD 990 | Gunnar of Hliarendi is killed by his enemies in Iceland |

| 1000 | The manuscript of Beowulf is written down |

| 1010 | Njal the lawyers farmhouse is burned in Iceland |

| Mid-11th century | The Song of Roland is composed |

| Late 12thearly |

| 13th century | The Nibelungenlied is composed |

| 1280 | Njals Saga is composed |

| 1389 | The Battle of Kosovo and death of Prince Lazar of the Serbs |

| 15th century | The first songs of the Kosovo Cycle are composed |

| 1488 | Publication of first Western edition of the Odyssey |

| 1755 | The Nibelungenlied is rediscovered |

| 1772 | First printed edition of Njals Saga |

| 1787 | Beowulf is rediscovered |

| 181415 | Publication of Serbian Folk Songs , edited by Vuk Karadi, containing songs of the Kosovo Cycle |

| 1835 | The Song of Roland is rediscovered |

Prologue

W E TEND TO think of epic stories as remote: faraway tales set long ago. But over the course of a few years, immersed in the epics of Europe, I grew to understand that these stories are all around us. As immediate as news reports, as explosive as blockbuster movies, as twistily compelling as the tales of a campfire bard.

The idea for this book started on a road trip across Europe. My wife was on maternity leave, and I was editing a book, so there was no reason we couldnt, as she put it, have fun for a few months. At the end of the summer, our eldest would be starting school, so this was our chance. We lurched from one mini-disaster to the next, rolling through seven countries in the space of four months, staying with friends, relatives and budget homestays through Airbnb. There was a visit to a mechanic after we punctured our tyres on a Sardinian dirt track, and we spent most of the ferry crossing to Sicily in the sick bay, after I forgot to strap our baby into his highchair. But we werent doing too badly: the kids were in one piece (each), we were still talking to each other and our ten-year-old Peugeot 206 was just about roadworthy.

It was an innocent, balmy time, flushed with the joy of exploring Europe through the eyes of small children. In Nuremberg, we revelled in the model trains at one of the continents finest toy museums and plodded, more soberly, around the site of the Nazi rally. In Syracuse, we attended a puppet show after wandering around an ancient Greek amphitheatre. Occasionally, signs of a hardening continent seeped through our little family bubble from racist graffiti in Hanover to African migrants asking for help in Sardinia. But dirty nappies and grazed knees tended to distract our attention. If the headlines got us down, we could always focus on the adventures of the Octonauts, or marvel at the brilliant woodwork of the German kindergartens .

How I loved Europe that summer: the brassy light beating down on the Mediterranean beaches, where the sea coddled our feet in blankets of turquoise; the dusty golden green of pine forests; the rituals you can still witness, from Sicilian signoras touching our babys feet and our older sons blond hair, then doing the sign of the cross, to graduates celebrating their degrees by kissing the bronze lips of the Gttingen goose-girl. Great coffee, delicious ice cream; and as their quality deteriorated, the sausages got bigger and so did the beer mugs.

But the talk back home was of severance. Identity politics was being marshalled for political gain; historical terms like Anglo-Saxon and hoary concepts like sovereignty were being triggered to canvass votes; Facebook profiles were being mined and divisive videos unleashed on YouTube by political strategists who derived their tactics from Sun Tzus Art of War and the nineteenth-century brinkmanship of Otto von Bismarck.

By the time we reached the Bavarian Alps, it had already happened: Britain had voted to end its forty-two-year political union with the mainland. Squeezed into a horse-drawn carriage clopping towards the castle of Neuschwanstein, I found myself brushing elbows with a friendly Dsseldorfer. You guys made a big mistake, he helpfully announced, scrolling down his iPhone to show me the freefalling pound. The castle was a Romantic folly built for the nineteenth-century aesthete, Mad King Ludwig, but we were in no state for castle touring. My wife managed to lose her purse in the carriage, and I wandered around in a daze, the words mad and folly bouncing around my head. Fortunately, at least one member of our party was on the ball.

Daddy, our three-year-old exclaimed, its a dragon!

My eye followed his finger across a vaulted arch towards a scaly, curly tailed beast, its breast pinned by a golden-armoured hero with a gleaming sword. We looked at each other and smiled, standing there under the mural.