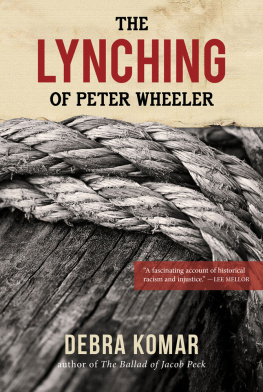

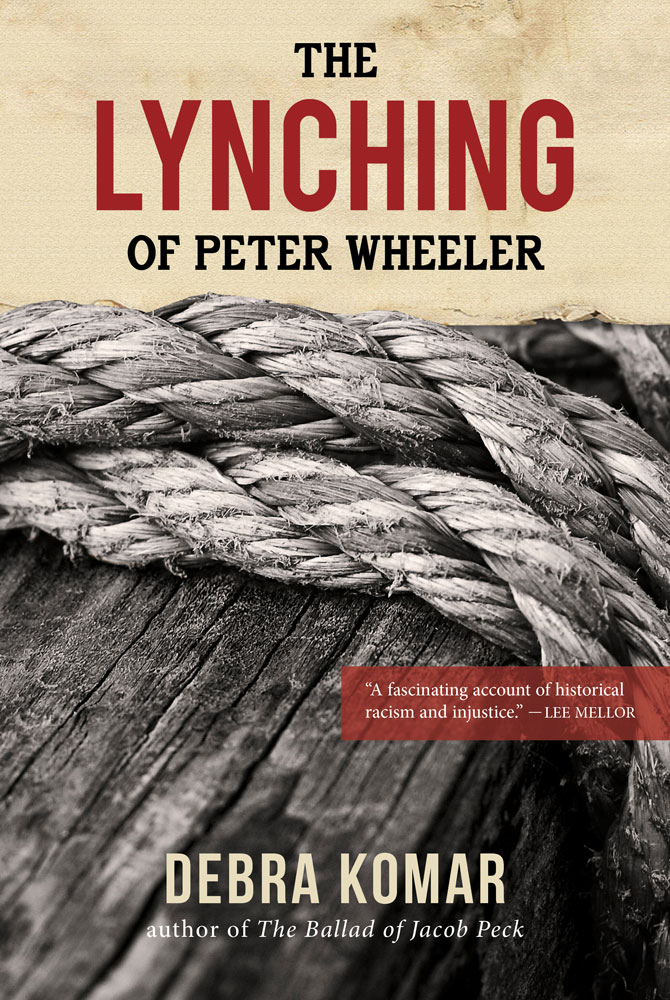

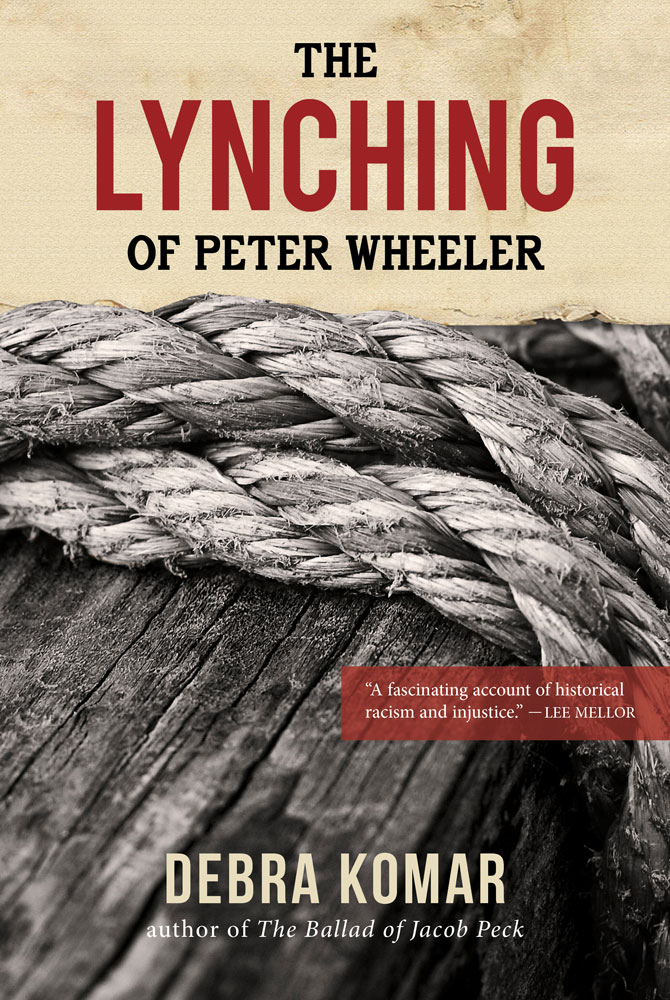

The Lynching of Peter Wheeler

Copyright 2014 by Debra Komar.

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher or a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). To contact Access Copyright, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call 1-800-893-5777.

Edited by Paula Sarson.

Cover image by Thomas Maxwell Rodger (www.thomasmaxwellrodger.com).

Cover and page design by Chris Tompkins.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Komar, Debra, 1965-, author

The Lynching of Peter Wheeler / Debra Komar.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-0-86492-417-9 (pbk.). ISBN 978-0-86492-603-6 (epub)

1. Wheeler, Peter, 1869-1896 Trials, litigation, etc. 2. Kempton, Annie, 1881-1896. 3. Lynching Nova Scotia History 19th century. 4. Trials (Murder) Nova Scotia. 5. Criminal justice, Administration of Nova Scotia History 19th century. I. Title.

HV6471.C32N6 2014 364.134 C2013-907609-3

C2013-907610-7

Goose Lane Editions acknowledges the generous support of the Canada Council for the Arts, the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund (CBF), and the Government of New Brunswick through the Department of Tourism, Heritage and Culture.

Goose Lane Editions

500 Beaverbrook Court, Suite 330

Fredericton, New Brunswick

CANADA E3B 5X4

www.gooselane.com

To my brother Mark,

who cant understand why all books

arent dedicated to him.

[T]he newspapers of a town are its looking glasses

it is here you see yourself as others see you.

Bridgetown Monitor , March 4, 1896

Contents

one

two

three

four

five

six

seven

eight

nine

ten

eleven

twelve

thirteen

fourteen

fifteen

sixteen

seventeen

eighteen

nineteen

twenty

twenty-one

twenty-two

twenty-three

twenty-five

twenty-six

twenty-seven

twenty-eight

twenty-nine

thirty

thirty-one

thirty-two

thirty-three

thirty-four

thirty-five

thirty-six

thirty-seven

thirty-eight

thirty-nine

forty

forty-one

forty-two

forty-three

forty-four

forty-five

forty-six

Preface

Violent crime renders us myopic. In the immediate aftermath of a murder, it can be impossible to see things clearly; emotions run high and the desire for vengeance often trumps reason. When the crime has racial overtones, justice is rarely colour-blind, and for cases that capture the media spotlight, the wave of punditry and prognostication that inevitably follows sweeps away all hope of ever separating fact from fiction. That is why crimes pulled from the annals of history have such value with distance comes clarity. The lessons are readily learned once the passion has dimmed, much like failed relationships. We even have the benefit of knowing how the story ends, or at least thinking we do. And it is through the benefit of the cold, clear lens of hindsight that we can finally raise questions for which there were no good answers in the heat of the moment.

One of the telltale symptoms of our crime-induced myopia is wrongful conviction. The need for swift justice easily morphs into a race to convict, and in our haste, the innocent are sometimes mistaken for the guilty. It can be nigh on impossible to recognize a false conviction while it is happening: the victims family demand closure and the wounded community wants nothing more than to once again feel safe and secure. The presumption of innocence that is at the heart of our justice system is a noble ideal, but it is no guarantee that we know an innocent man when we see one, particularly when we are blinded by the need to find a guilty one. And so, if proximity to the crime blinds us to our mistakes, it stands to reason that a little distance may bring the truth into focus.

This book began with a simple question: is it possible to recognize a wrongful conviction buried deep in our nations past and, in so doing, identify how and why the mistake occurred? The erroneous judgment could cut either way: an innocent person falsely accused or the guilty party set free. Since a wrongful conviction inherently implies error, I would need to apply modern forensic science and investigational standards to a crime in antiquity in order to establish a credible basis for an erroneous verdict. To that end, I began searching through past criminal cases, looking for files with extensive surviving documentation, including trial transcripts, autopsy records, and police reports. In addition, the outcome of the case had to rely in some measure on physical evidence fingerprints, blood, footprints, or tool marks to name just a few and the vestiges of that evidence had to be retained in the archives, at least in the form of testimony and reports from the original expert witnesses or investigators. It was a tall order; the historical archives relating to crime are notoriously spotty or even entirely absent. Furthermore, forensic science was not recognized as a discipline until the early part of the twentieth century and its precursors rarely made an appearance in nineteenth-century courtrooms. After months of searching, I found what I was looking for in my backyard: the murder of Annie Kempton in Bear River, Nova Scotia, in the winter of 1896. Peter Wheeler was later convicted and hanged for the crime.

Although Annies death was front-page news in its day, the case has largely been forgotten outside of Bear River. It has been the subject of a single work of fiction: Arthur Thurstons 1987 self-published novel, Poor Annie Kempton: Shes in Heaven Above , in which the author imagines having conversations with the sagas key players. In the past decade an original play based on the crime was produced but this, too, was a creative work loosely founded on fact. While there have always been doubters and rumblings about Peters innocence over the years, this is the first factual public examination of the case since his trial and the first credible attempt to challenge his conviction. Initially, I briefly toyed with the idea of trying to identify the real killer but as I began to research Wheeler in earnest, the mechanics of how and why he came to be falsely accused and convicted were far more compelling. Those interested in pursuing alternative suspects will be heartened to learn that, in the course of laying out the case for Wheelers innocence, all the collected evidence is carefully detailed. Hidden within is the identity of the actual killer and your guess is as good as mine.

For more than twenty years as a practicing forensic scientist, I frequently testified as an expert witness but it was never my job to tell the jury who was innocent and who was guilty. My role was to identify, collect, and analyze all the available evidence; develop a cohesive narrative that explained that evidence; present it in a clear manner; and help the triers of fact to understand the science and technical aspects of the testing process. It then fell to the jurors to add that information to the other testimony they heard and reach their verdict. The same methodology follows here. My goal was to collect and analyze the information; call your attention to the evidence or testimony that warrants your consideration; develop a cohesive narrative; and guide you through the technical aspects of the research. After that, it falls to you, the reader as the thirteenth juror, to reach your own conclusions as to what really happened in Bear River in 1896.

Next page