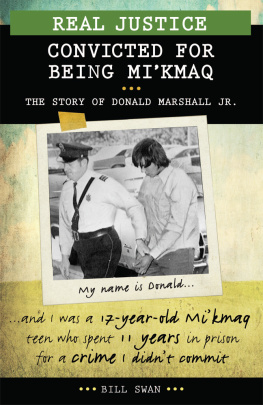

Donald Marshall Jr. was convicted and sent to prison, in part at least, because he was a Native person.

Royal Commission on the Donald Marshall Jr., Prosecution.

The dialogue in this book is taken for the most part directly from transcripts of hearings and from statements given by witnesses. Some latitude has been taken to create a narrative flow to the story, but on all key points of testimony the quoted material is from official documents.

Foreword

The story of Donald Marshall Jr.s wrongful conviction is a story of courage and betrayal, of perseverance and luck. Surviving the ordeal of eleven years of wrongful imprisonment described by many wrongfully convicted persons as the equivalent of being buried alive required Donald Marshall to draw on depths of strength he had no reason to know he possessed. Eleven years of struggle to survive the harsh realities of prison and then eight more years after his release before being exonerated by the Royal Commission of Inquiry that examined how the criminal justice system had betrayed him.

The Royal Commissions 1990 report was a searing indictment of the system of justice that wrongfully convicted an innocent seventeen-year-old in 1971 and kept him locked up while he grew into adulthood. Wrongful conviction robbed Donald Marshall of far more than just his liberty. The eldest son of the Grand Chief of the Mikmaw Nation, Donald Marshall was deprived of the kinship of his large, close-knit family and community; separated from his language and culture; and subjected to the daily tensions, humiliations, and violence of prison life. His existence was one of survival and struggle, long after he walked out through the prison gates.

When Donald Marshall was released from prison in 1982, freed on bail following the reopening of his case, he faced the ordeal of trying to establish his innocence. Although acquitted in 1983 of the murder of Sandy Seale, the victory was a bitter one: the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia (Appeal Division) laid responsibility for his wrongful conviction at his feet. Only the painstaking work of the Royal Commission of Inquiry finally exonerated him, finding that it was the legal system that had failed Mr. Marshall at virtually every turn.

The Royal Commission came to the painful conclusion that racism played a significant role in Mr. Marshalls wrongful arrest and conviction. Had Mr. Marshall been White, the Commissioners found, the investigation by the Sydney police would have taken a different course. The Commissioners concluded that Donald Marshall was convicted and sent to prison, in part at least, because he was a Native person describing the evidence supporting this inescapable conclusion as persuasive. They characterized their determination that racism played a role in Mr. Marshalls imprisonment as one of the most difficult and disturbing findings this Royal Commission has made.

The reality that factors such as race and socio-economic status contribute to making a person more vulnerable to being wrongfully convicted is deeply troubling. Indeed, as Donald Marshalls story reveals, his Aboriginal status made him vulnerable to being a victim in the very attack that killed Sandy Seale, who was himself a racialized person. It took the complete failure of the criminal justice system in Donald Marshalls case to transform him from the genuine victim of a racist attack to the falsely accused perpetrator of the crime.

Donald Marshall Jr.s wrongful conviction was exposed at a time when Canadians and the Canadian criminal justice system had not yet confronted the extent to which the factors in his case, and those unique to subsequent cases, had operated to send other innocent people to prison for murders they did not commit. The wrongful convictions of David Milgaard, Guy Paul Morin, Thomas Sophonow, Gregory Parsons, Randy Druken, Ronald Dalton, James Driskell, William Mullins-Johnson and Steven Truscott were also eventually overturned with Royal Commissions or Courts of Appeal exhuming the errors that led to these men being buried alive by a flawed justice system. And this list is not exhaustive. With its legacy of wrongful convictions, the Canadian criminal justice system cannot afford to be complacent. Not only do wrongful convictions inflict a terrible toll on the innocent and their families, and ultimately on public confidence in the criminal justice system, but the broader community also remains at risk when the wrong person is locked away. It is a chilling fact that through all the years Mr. Marshall watched his life pass by in prison, Sandy Seales killer was free in the community.

Donald Marshall Jr. was eventually compensated for his wrongful conviction by the Province of Nova Scotia, accepting the recommendations of a Royal Commission of Inquiry that examined the issue. His parents also received a small amount of compensation for their losses. All those years of travelling to visit their bewildered, angry son in prison. Raising their family without their first-born. Donald Marshall Jr.s brothers and sisters growing up without him. The stigma of having a child convicted of murder. The agony of knowing he was innocent.

So much time has passed since Sandy Seales murder in May 1971 a tragedy that set into motion the awful forces that saw another young man lose a significant part of his life that many Canadians have forgotten or do not know Mr. Marshalls harrowing story. Mr. Marshall, of course, did not have the luxury of forgetting what was done to him. He could never forget. No amount of compensation could have given him back what was taken from him by a justice system that was ready to believe, and to keep believing, that he was a killer. Donald Marshalls story is not just a cautionary tale about the criminal justice system, however, and how it can and must be improved; it is also a story of grit and integrity, of not giving up, of not losing all hope. It is a story of strength and spirit, of personal and cultural endurance, of the ultimate triumph of truth over lies. It is a story that Canadians should commit to memory. A story that can challenge and inspire. A story that tells us it is vital to believe, as Donald Marshall believed, that no matter what adversity we confront as individuals or more broadly as a society, we must not give up, even in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds.

Anne S. Derrick

Derrick was one of Marshalls counsel at the Royal Commission of Inquiry on his prosecution; counsel to Marshall at the inquiry concerning the adequacy of compensation paid to him; and counsel (with Professor Archie Kaiser) to Marshall before the 1990 Inquiry Committee of the Canadian Judicial Council examining the conduct of the judges who sat on the 1982 Appeal Reference into Marshalls murder conviction. She is now a judge of the Provincial Court of Nova Scotia.

Chapter One A Stroll In The Park

May 28, 1971

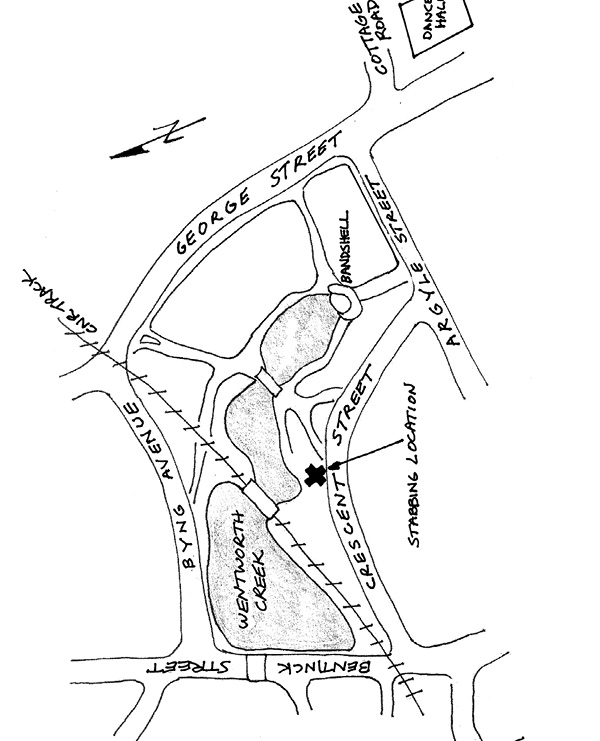

Donald Marshall Jr. pulled on a cigarette and scuffed his toes into the bare ground at Wentworth Park.

Crappy night , he thought.

First, he had missed the dance. He was late returning from Halifax. By the time he arrived at the St. Josephs Church hall, the dance was sold out. When youre seventeen and live in a place like Sydney, Nova Scotia, where not much ever happens, missing a dance is a big deal.

At just over six feet, with an athletic build, Donald moved like someone confident in his good looks. When he couldnt get into the dance, he hung around, looking for someone he knew. There would always be somebody.