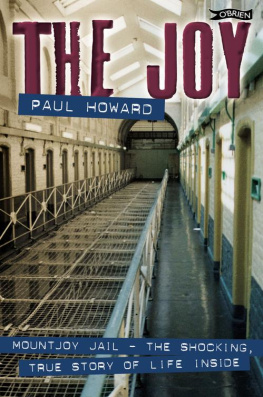

Tim Carey wrote the bestselling Mountjoy The Story of a Prison (2000), Hanged for Ireland (2001) and Croke Park A History (2004), and he co-wrote The Martello Towers of Dublin (2012). A regular media contributor, he is a graduate of Trinity College and University College Dublin, and is currently heritage officer with Dn Laoghaire-Rathdown County Council.

Follow him on Twitter @tim_carey1

For Sinad, Jennifer and Aaron.

Contents

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, I would like to thank all of those who were involved with the four series of Ceart agus Coir that were broadcast by TG4 and which laid the foundations for this book. In particular, I would like to thank sincerely Mike Keane, director of Midas Productions and Reelgood Facilities, and Rosie Nic Cionnaith. I am also very grateful to Edel Quinn, Finnuala N Chobhin, Catherine Quinn, Cleona Nic Chormaic, Cleona N Chrualao, Colm Bairad and Cara Ronan.

I am indebted to Sean Reynolds of the Mountjoy Prison Museum whose insights into the prisons history were invaluable. I would also like to thank Jim Mitchell and Sean Aylaward, former director, of the Irish Prison Service for allowing access to prison files and for generally being extremely supportive of the various prison research projects I have undertaken.

A huge debt of gratitude is due to the staff of the National Archives of Ireland, in particular the former Director David Craig and Acting Director Frances Magee; Aideen Ireland, Head of Reader Services; archivist Gregory OConnor; and last, but by no means least, the staff of the reading room, including Ken Robinson, Christy Allen, David ONeill and Paddy Sarsfield, who dealt with my queries with great patience and were always helpful. Many thanks also to the National Library of Ireland and its reading room staff.

The advice and support of my agent, Sallyanne Sweeney of Watson, Little, was greatly appreciated. Thanks are also due to Vanessa OLoughlin of www.writing.ie. My employers Dn Laoghaire-Rathdown County Council have always been supportive of my writing endeavours and for that I am very grateful.

The family of Sean Kavanagh, former Governor of Mountjoy Prison, very kindly made his papers available to me during various periods of research. Professor Ian ODonnell, Head of the Institute of Criminology in University College Dublin, was most generous with his encouragement, support and advice. The late Marcus Burke gave valuable insights into the Harry Gleeson case; as did the members of the Justice for Harry Gleeson Group. Thanks are also due to Des Nix.

I am extremely grateful to my wife Sinad and children Jennifer and Aaron for their support and encouragement throughout this project. Sinad also assisted by reading the many drafts and making many helpful suggestions and comments. Both she and our children, put up with being without me for a prolonged period, so now I owe them ...

Finally, I would like to thank Gillian Hennessy and all at The Collins Press for being excellent publishers.

Tim Carey

October 2013

Introduction

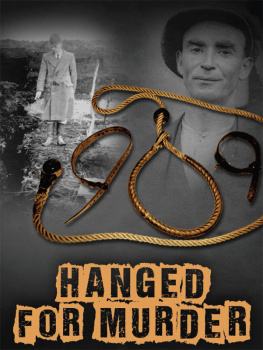

The Executions

B ehind the walls of Mountjoy Prison on Dublins North Circular Road lie the remains of twenty-eight men and one woman who, between 1923 and 1954, were convicted of common murder and executed in the prisons hang house. This book tells their stories.

To most, the majority of people who feature in this book will be completely unknown. These are not people whose lives have been celebrated, whose deeds have been widely regaled. A few publications have previously cast light on some of these stories. Marcus Bourkes Murder at Marlhill Was Harry Gleeson Innocent? and Dermot Walshs Beneath Cannocks Clock The Last Man Hanged in Ireland give detailed accounts of two of the execution cases. Kenneth Deales Beyond Any Reasonable Doubt? (1971) looks at a variety of famous trials that include some of those which ended in an execution. Terry Prones Irish Murders (Vols I and II, 1992 and 1994) also included some of the executed. However, none looked comprehensively at all of those who were put to death by the state.

Their trials took place at Green Street Courthouse, Dublin, and after the juries returned guilty verdicts, the presiding judges donned their black caps not caps, as such, but small square pieces of black silk and read out the death sentences:

The sentence of the court are and it is ordered and adjudged that you [name of prisoner] be taken from the bar of the Court where you now stand to the prison from whence you last came and that on [day] the [date] day of [month] in the year of Our Lord [year written out] you be taken to the common place of execution in the prison in which you shall then be confined, and that you be then and there hanged by the neck until you be dead and that your body be buried within the walls of the prison in which the aforesaid Judgement of Death shall be executed upon you.

What happened next was clearly outlined in the prisons administrative documents. For each of the twenty-nine executions the process was the same.

From the moment a condemned prisoner was returned to Mountjoy two warders remained with them at all times, to ensure that they did not kill themselves and cheat the Irish state, on behalf of the people, of exacting its retribution. It was also their responsibility to help to keep the prisoners spirits up, to make their last days pass as easily as possible. For their comfort the prisoner would be given cigarettes, an improved diet though there was no request granted for a last meal and other small luxuries, including newspapers and board games such as chess and draughts. The prisoner would then be put into the condemned cell, a large double cell located near the execution chamber at the end of D wing that allowed the prisoner to be brought to the hang house quickly when their time came.

Once the government had decided against a reprieve the governor would send word to the executioner, giving them the date of the hanging they were always carried out at 8.00 a.m.

Though a new state had come into being and there was some discussion about hiring an Irish executioner, for the sake of expediency and because of the perceived difficulty of getting an Irishman to take on a job that had so recently involved the execution of republican prisoners by the British, the Irish authorities came to an arrangement with Britains executioners to continue to carry out the role. Apart from the first, who was executed by John Ellis, all of the twenty-nine executions in Mountjoy were carried out by members of the Pierrepoint family most were carried out by Tom, with the last four by Albert. However, well into the period with which this book deals there was one short-lived attempt by de Valeras government to train an Irish hangman. His name was James OSullivan and he was from Cork but to protect his identity he operated under the false name Thomas Johnston.

In a travel document issued by the authorities James OSullivan travelled to Strangeways Prison, Manchester, in 1945 to learn the skills needed to hang a person. However, Albert Pierrepoint was far from impressed. In his autobiography,

Next page