Titles in the series Critical Lives present the work of leading cultural figures of the modern period. Each book explores the life of the artist, writer, philosopher or architect in question and relates it to their major works.

In the same series

Michel Foucault

David Macey

Jean Genet

Stephen Barber

Pablo Picasso

Mary Ann Caws

Franz Kafka

Sander L. Gilman

Guy Debord

Andy Merrifield

Frank Lloyd Wright

Robert McCarter

James Joyce

Andrew Gibson

Noam Chomsky

Wolfgang B. Sperlich

Jorge Luis Borges

Jason Wilson

Erik Satie

Mary E. Davis

Georges Bataille

Stuart Kendall

REAKTION BOOKS

For Vanessa Corra

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

33 Great Sutton Street

London EC1V ODX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2007

Copyright Stuart Kendall 2007

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in Great Britain

by Cromwell Press, Trowbridge, Wiltshire

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Kendall, Stuart

Georges Bataille. (Critical lives)

1. Bataille, Georges, 18971962 2. Bataille, Georges,

18971962 Influence

I. Title

194

ISBN 13: 978 1 86189 327 7

ISBN 10: 1 86189 327 2

Contents

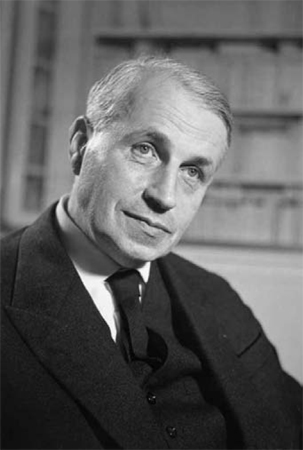

Georges Bataille in 1961.

Introduction: Ecce Homo

Opposition is true friendship.

William Blake

Shortly after the death of Georges Bataille in 1962 the French Ministry of Culture banned his final book, Les Larmes dEros (The Tears of Eros), as an outrage to morality. The book sketches a history of desire from prehistory to the present, largely in images from the tradition. The most shocking images those of a Chinese torture, the Leng Tche were erotic only in a sadistic sense that most readers would hardly embrace or even recognize. In Batailles argument, the images evidenced the proximity of opposites sex and death, horror and delight, religious deliverance and the violation of communal law. In the proximity of opposites, Bataille discerned a capacity for infinite reversal, a passage from the most unspeakable to the most elevated, a deliverance from the most acute agony to the highest ecstasy.

Over a lifetime of writing cut short by death no other book with Batailles name on its cover had ever been banned. For forty years he had secreted his identity behind pseudonyms and published his most scandalous works in small, rather sumptuous, limited editions. The many writings that he did sign essays, novels, poetry; studies in economics, anthropology and aesthetic criticism were scandalous only to careful and attentive readers. As an employee of the Bibliothque Nationale, Bataille could not afford to be prosecuted: he would have lost his job. More interestingly however, the drama of pseudonymous publication the play of identities, the revelatory masks was itself central to Batailles literary endeavour. Bataille did not write for recognition, far from it: He wrote to disrupt the assumptions and processes that might make recognition possible. He wrote to ruin words, to reveal the ultimate impossibility of complete communication and to open a sphere wherein the impossible the heterogeneous, the different, the sacred could be communicated. In keeping with this strategy, in The Tears of Eros Bataille spoke without speaking, through the arrangement of images: his final testament was largely a silent one. That his book was banned only testified to the virulence of its contagious power, doubling its silent allure.

A counter-movement was, however, already in motion. A fount of recognition had begun to flow; an effect of friendship and necessity. In 1963 Critique the journal Bataille founded in 1946 memorialized him in the first of its special issues.

The post-structuralist trend in Western thought is in fact impossible to imagine without him. Roland Barthes, Jacques Derrida, Jean-Franois Lyotard, Julia Kristeva and Jean Baudrillard each wrote about Bataille and under his influence on numerous occasions. In 1972 the Tel Quel group organized a week-long conference on Bataille and Artaud. It would be the first of many such conferences held in the decades since Batailles death. During the 1980s the art critics associated with the American journal October devoted a special issue to Bataille, signalling the centrality of his work to their enterprise.

New editions of Batailles works and new books and anthologies about him continue to appear. The reasons for this ongoing fascination a fascination which shows no signs of abating are myriad, confusing, and conflicted. They are primal Bataille was among the foremost writers of pornographic fiction in his era, he was a devotee of horror and atrocity; an extreme thinker for extreme times. And they are poignant Bataille fashioned a method for the analysis of whole systems that may yet prove to be among the most essential critical developments of the twentieth century; he wrote with endless compassion for human frailty and devotion to human freedom. As a psychologist and philosopher of language, a novelist and a poet, a religious devotee and a mystic, he explored the uses and limits of knowledge and communication in human life more diversely, more thoroughly than anyone else in his century. No other writer contributed so substantially to so wide a range of fields.

Yet, like his progenitor, Friedrich Nietzsche, Georges Bataille lived a profoundly untimely life. Always on the margins, he was never at home in his time, and his life and work remain obscure to us even now.

Bataille wrote against violently against each of the main intellectual, artistic and political trends of his era. An atheist in a deeply Catholic country, he rejected Surrealism, Marxism and Existentialism in turn. To Bataille, Surrealism was an inconsequential idealism, a frenzy in art rather than in life; Marxism failed to found its materialism in the energies animating the material world and Sartrean Existentialism remained bound by a theory of consciousness that had been betrayed by the passage of time. In the structuralist era Bataille pushed structuralist methods to the point of paradox, of contradiction. He rejected both psychoanalysis and the French School of Sociology as incomplete, while retaining their essential insights, refashioned to his needs. Bataille was not simply an atheist: to borrow a phrase from LExprience intrieure (Inner Experience), he threw himself on the throat of his god, he sacrificed his own highest values, and the values of his time, in an act of creative destruction.

Bataille did not seek new knowledge. Rather, he sought experience, sovereign experience, which for him meant the experience of boundless freedom: freedom from language, discipline, utility, culture and identity; an impossible freedom. The issue as Bataille wrote, was not that of the attainment of a goal, but rather of escape from those traps which goals represent.

To simply say that Bataille wrote against the major currents of thought in his time is to overlook his methods. He wrote against these currents by writing within them, by writing in response to them, in response to both the dead writers of the tradition and the living legacy the disciples of those writers. Most importantly, he wrote in the context of friendship.