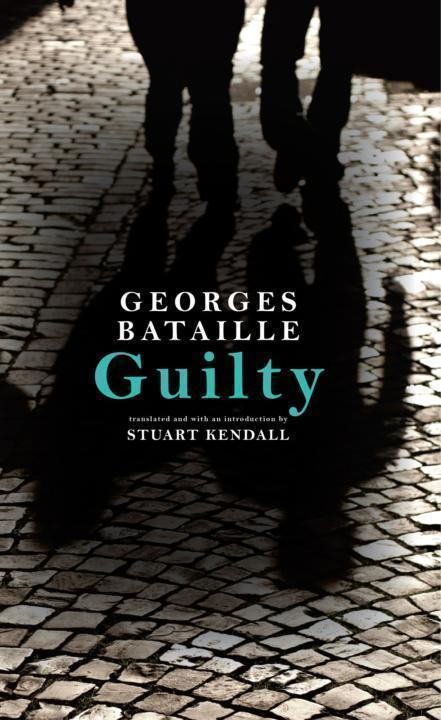

Guilty: Le Coupable by Georges Bataille

Le Coupable

revised edition

GEORGES BATAILLE

Translated and with an introduction by STUART KENDALL

vii

ix

Guilty

FRIENDSHIP

THE MISFORTUNES OF THE PRESENT TIME

LUCK

THE DIVINITY OF LAUGHTER

APPENDICES

Even when I had my head in the clouds, Lucie kept my feet on the ground and my thoughts directed toward the really important things in life: the secret lives of animals, puzzles, picture-books, sidewalk chalk, and rumdums.

Vanessa Correa once again supported and indulged me in countless ways on this, yet another fool's errand, which has been with us now, from anticipation to execution, through three houses in two states. I count myself lucky every day that she manages to smile as my compulsions lead us down unlikely roads, and fortunate too that she appreciates the incredible richness of our life together even in the absence of recognized wealth. As she knows, living well is the sole justification and authority. In this and all things, she is my true companion.

Gradually it has become clear to me what every great philosophy so far has been: namely, the personal confession of its author and a kind of involuntary and unconscious memoir; also that the moral (or immoral) intentions in every philosophy constituted the real germ of life from which the whole plant has grown.

-Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, 6

It is not given to everyone to have his private tasks of meditation and reflection so happily coincident with the public interest that it becomes difficult to judge how far he serves merely himself and how far the public good.

-Soren Kierkegaard, Philosophical Reflections

Georges Bataille started a diary during the first days of World War II. Already on the first page, words introducing the war diary inform the reader that the book is not meant to be a record of the war at all. Rather, we gradually learn, it is to be a diary of inactivity, implicitly opposed to the engagement of combat; it is a record of uselessness. Le Coupable (The Guilty One or Guilty) is a book written under erasure. Doomed from the outset, intentionally self-defeating, its incoherence illustrates the hopelessness and loss implicit in human life. The perfection of the conceit is part of its magic and part of its undoing.

The book is thus not exactly the war diary it announces itself to be, nor is it-in its final, drastically edited and recast form-much of a diary at all. Georges Bataille's fractured prose and poetry scatter across and off the pages in several directions at once, ranging through discursive registers and over disciplinary boundaries: literary, philosophical, and theological. His medias res meditations and notations would ultimately provide him with material for several future works, in some ways almost the entirety of his career as a writer of books. In the pages of Guilty, one glimpses the embryonic images, forms, and topics of Madame Edwarda and L'Experience interieure (Inner Experience), of Le Part Maudite (The Accursed Share) and L'Impossible. And I mean this quite literally, not only does one find the experiential and analytic prose, the poetic fictions and fictionalizations of these diverse works, but one finds precise images and examples from which these works derive. Later, Bataille expanded Guilty with the addition of an introduction and an enigmatic hybrid text, Alleluia: The Catechism of Dianus, to recast the work as volume 2 of his multivolume La Somme Atheologique (The Atheological Summa).

Guilty is thus many things at once: a diary and a workshop, an accounting and an experiment. The jittery prose veers wildly, jumping between topics and tasks, in search of a ground but reveling in groundlessness, literally and literarily falling apart. This is the book in which Georges Bataille set himself apart as a writer.

Prior to writing Guilty, Bataille had not published a full-length work under his own name. Someone named Lord Auch took credit for a small, clandestine edition of L'Histoire de l'oeil (Story of the Eye) back in the 1920s, and "Georges Bataille's" publications amounted to nothing more than a few pamphlets and a number of articles in obscure political and philosophical journals.' The one fulllength work the author had both completed and attempted to publish, Le Bleu du ciel (Blue of Noon), had been either suppressed or abandoned, it's hard to say which.2 What's more, when Bataille first decided to publish extracts from the notebooks that would become Guilty, in Jean Paulhan's journal Mesures in 1940, he choose to do so under the pseudonym Dianus.3 Only later would he claim the text as his own.

All of this in mind, Guilty records Bataille's first steps, however faltering and uncertain, as a writer of books. Significantly, Bataille did nothing to clear up the uncertainties of the text: quite the opposite in fact, he exacerbated them both intellectually and editorially. Guilty walks a carefully crafted line of precisely observed chaos and disorder.

As noted above, Bataille began writing Guilty as a diary or journal rather than as a book, though he did seem to have some kind of "book" in mind. Bataille had never really kept a journal before, certainly not one like this. At the time he was also trying without success to write two other books, a phenomenology of eroticism and an early draft of TheAccursed Share.4 Guilty was something on the side. After two years, he experienced a breakthrough in his thought and abandoned these other works and the notebooks for Guilty to write Madame Edwarda and then part 2 of Inner Experience, "Torture." The first half of Guilty is the record of that decisive period of intellectual and creative struggle. In his notes, he will repeatedly emphasize its importance to him.

In 1942, Bataille returned to Guilty after submitting Inner Experience for publication at Gallimard. He also began writing poetry and a new kind of fiction that was all but indistinguishable from Guilty itself; these writings would become the texts of Le Petit (The Little One) and L'Impossible (including The Oresteia, The Story of Rats, and Dianus).

Roughly speaking, parts 1 and 2 of Guilty correspond to the period prior to Madame Edwarda, part 3 to the period coincident with Madame Edwarda and Inner Experience, and part 4 and the appendices to the period following Inner Experience, alongside The Oresteia. Alleluia was written later, with Method of Meditation.5

Guilty, then, might be seen as both a catalyst and a crucible: pages in which Bataille wrestled his obsessions into an extended and publishable form for the first time. Indeed, in the first half of Guilty, Bataille inaugurated a new relationship to himself in writing. This relationship had its intellectual antecedents, as he demonstrates in part 3 of Inner Experience, but here, in Guilty, Bataille began to explore his essential solitude in a substantially new way. Later, he would refer to Guilty, Inner Experience, and On Nietzsche, accurately, as his first books.6

Next page