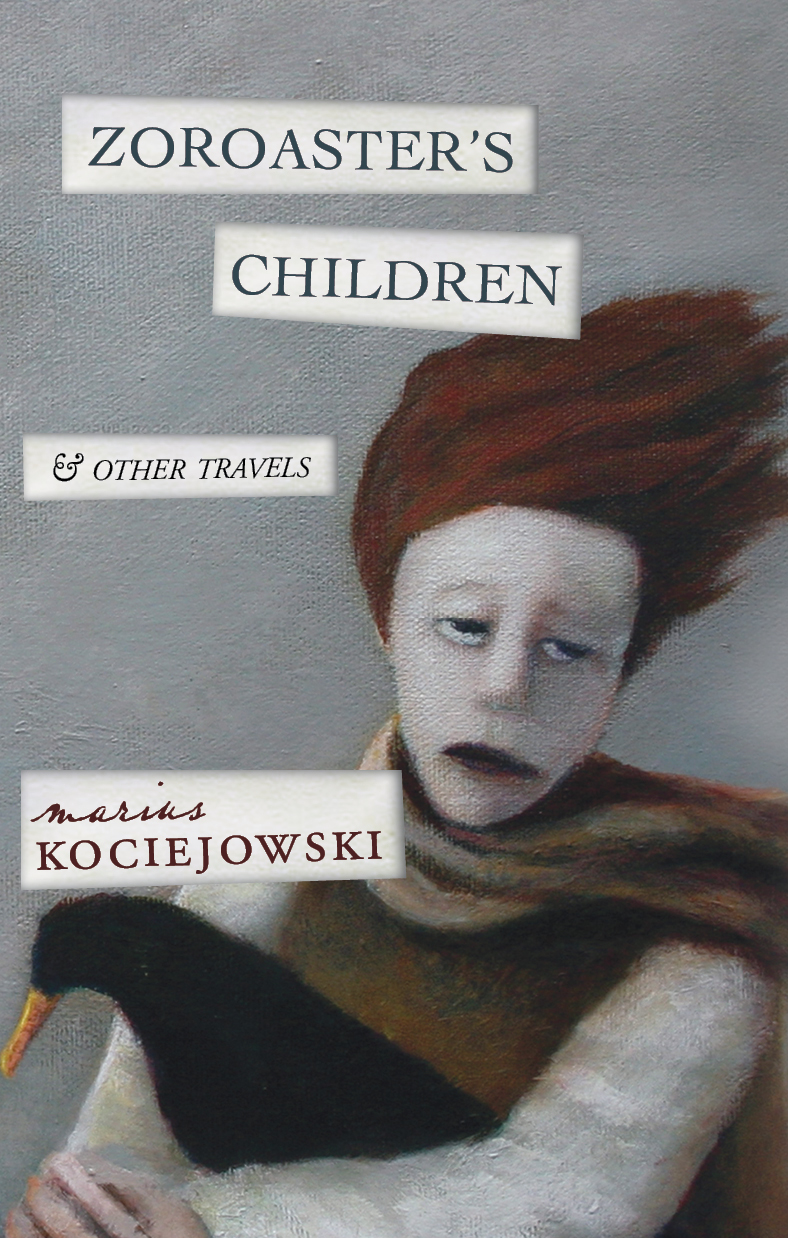

Zoroasters Children

X

and other travels

Marius Kociejowski

Biblioasis

Windsor, Ontario

Copyright Marius Kociejowski, 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher or a licence from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For an Access Copyright licence, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

First Edition

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Kociejowski, Marius, author

Zoroasters children and other travels / Marius Kociejowski. Essays.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-77196-044-1 (paperback).--ISBN 978-1-77196-045-8 (ebook)

1. Kociejowski, Marius--Travel. I. Title.

PS8571.O64Z43 2015 C814.54 C2015-903733-6

C2015-903734-4

Edited by Dan Wells

Copy-edited by Allana Amlin

Typeset and designed by Chris Andrechek

Published with the generous assistance of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council. Biblioasis also acknowledges the support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund and the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Book Publishing Tax Credit.

for Bobbie

silent companion of some of these travels

Some Places Ive Been To

I ve been reading Hermione Eyres Viper Wine (Jonathan Cape, 2014). The writing dazzles, and, at times, with its many stretches of Jacobean pastiche, almost too much so. A woman I know wont go near the book for its virtuosic glare. The novel is set in 1632 with fanciful intrusions, sometimes to extraordinary effect, from the present day, the arrival of an acid cloud above London being one such instance. Id made the mistake of mentioning to my friend that David Bowie makes a fleeting appearance. Orlando Gibbons, I could hear her think, come hither. Its probably too late to invite her to sample the following passage:

So soft and suggestible are we, she thoughtmen and women bothand there is so much about us still unknown, and yet people adventure into foreign lands. I would sooner go to the edge of a womans tear duct, she thought, as to the great Cataracts of the Nile, to know the nerves behind a flayed mans face, before I knew Madagascar, or the moon.

Actually, ostrich-plumed hats off to her, Miss Eyres is a marvellous book, and the words I quote above are yet another instance of how certain works, or even single passages in them, can so neatly fall into place. I had been contemplating how best to begin an essay that is designed to segue into the other pieces in this book and her words come at just the right time. I think that with respect to my own geographical coordinates I stand midway between a womans tear duct and the waning moon.

I have been described, though not often, as a travel writer, an appellation that vaguely embarrasses me. A couple of books, which sit in the travel sections of bookshops, have had the effect of making me into what I may not be. I do not have the means to be a traveller or to be able to just pick up and go. Also Im idle. Oblomov outstrips me. Im not a tourist either. A tourist moves inside a bubble; a traveller forgoes the safety of that bubble. I am sufficiently enough of a coward to not go risking my hide, but then again, I have gone where many think it folly to do so. There have been instances. Somebody I know says hed never go anywhere with me. Im reckless in his eyes. But does this make me a traveller? Then again, who among us is not a traveller, stumbling upon vortexes, which, like certain dreams we have, we try later to give meaning to? Are we not travellers from the day we are born? And are we not at risk all the time? Yet the ease with which we can go places, even dangerous ones, is such that we need to rethink the very notion of what it is to travel. There is nowhere on the planet one cant get to, and to a fair degree this has made redundant the idea of a narrative, and so I think it has become incumbent upon authors to write not so much about getting to a place as in being able to write out of it . A traveller goes with what he has, which, one hopes, includes a fair measure of knowledge but which is useful only to the degree that same knowledge does not cloud what is actually in front of his eyes.

The travel writers I know are almost always on the move, they wear exotic clothes, they have survived snake bite, and they speak the more remote dialects of already impenetrable languages. One of them, a most fascinating figure, was recently spotted heading a tour of the brave on the North West Frontier and seemingly impervious to the worlds jittery state. Theres a book he appears to be in no hurry to complete. Im not so sure he has even begun it. The book may be him alone . One day his name will grace a school of studies. If theres a desire in me to separate myself from the travel writing crowd, it is not that I disparage the works of those who are in it, for I believe much of the best English prose is to be found in what they produce, but rather because when compared to the coloratura of their lives mine pales. This said, I would sooner sit with them than with a group of poets. (I have been called a poet, too, a label with which I am rather more comfortable because its so threadbare.) So, why travel writers rather than poets? Simple. While the latter bemoan a world that insufficiently recognises them, the world is what the former most like to describe.

I dont have languages and am quite unable to retain such words and phrases as I have picked up here and there, but then I have met people who do, who converse with ease, who do not pay over the odds for an aubergine, and yet are no wiser to the people whose tongues they speak. Often they will be the first to lay the charge that one cannot get close to the soul of a country without first knowing its language. The curious thing is that those who say so tend not to be writers. All the same, its difficult to argue with them. The best travel writers speak the lingo, of course, and I shall be forever in awe of them. Wilfred Thesiger spoke fluent Arabic. I met him once. So nervous I was in the presence of this greatest of twentieth-century travellers all I could think to ask him was the identity of some birds that years before Id seen flying in extraordinary formation above the Sahara. They flew in a constantly shifting pattern too intricate for language to describe. I can see them still, but I cant tell you what I see. I made a stab at it with Thesiger. He thought for a minute and said, gruffly, and with great authority, Sand birds. When I mentioned this to someone who knew him the response was, Oh, Wilfred knows bugger all about birds. While I am fully aware of my linguistic handicap, which admittedly is a serious one, and am ornithologically challenged (though not as badly as some people), I would suggest that there are ways by which one might compensate a little.

Mind you, Ive been extraordinarily lucky: I could not have written my two books on Syria without the help of a couple of people, Arabs both, whose mastery of the English language and their quickness of mind were such that they could translate with the rapidity of a UN interpreter and at the same time preserve the nuances, and, most importantly, the humour, of the original. The incredible thing is that they were not academics but picked up English mostly by serendipity, somewhere between a stack of movie magazines and the marketplace. Even if I spoke Arabic passably well, I doubt Id be able to suck the juice from the pomegranate. What I mean by this is my getting at the deeper meaning seeded inside language. What greatly helped me is that my Arab friends were willing to subscribe to my sometimes batty schemes. Id be nowhere without them, still splashing about in the shallows, spouting generalities. Generality, and not, as some like to say, preconceived notions, is the true enemy of ones deeper enquiries into human nature.