()

Copyright 2015 by Thomas Kunkel

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint and division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York.

R ANDOM H OUSE and the H OUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Simon & Schuster Publishing Group for permission to reprint a telegram from M. Lincoln Schuster to Joseph Mitchell dated November 24, 1944 (New York: Simon & Schuster, Inc.). All rights reserved. Used with the permission of Simon & Schuster Publishing Group.

L IBRARY OF C ONGRESS C ATALOGING - IN -P UBLICATION D ATA

Kunkel, Thomas

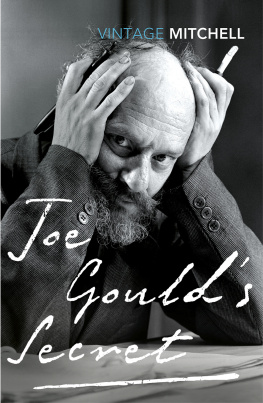

Man in Profile: Joseph Mitchell of The New Yorker/Thomas Kunkel.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-375-50890-5

eBook ISBN 978-0-8129-9752-1

1. Mitchell, Joseph, 19081996. 2. Authors, AmericanBiography.

3. JournalistsUnited StatesBiography. 4. New Yorker

(New York, N.Y.: 1925) I. Title.

PS3525.I9714Z69 2015

818.54dc23

[B] 2014024105

eBook ISBN9780812997521

www.atrandom.com

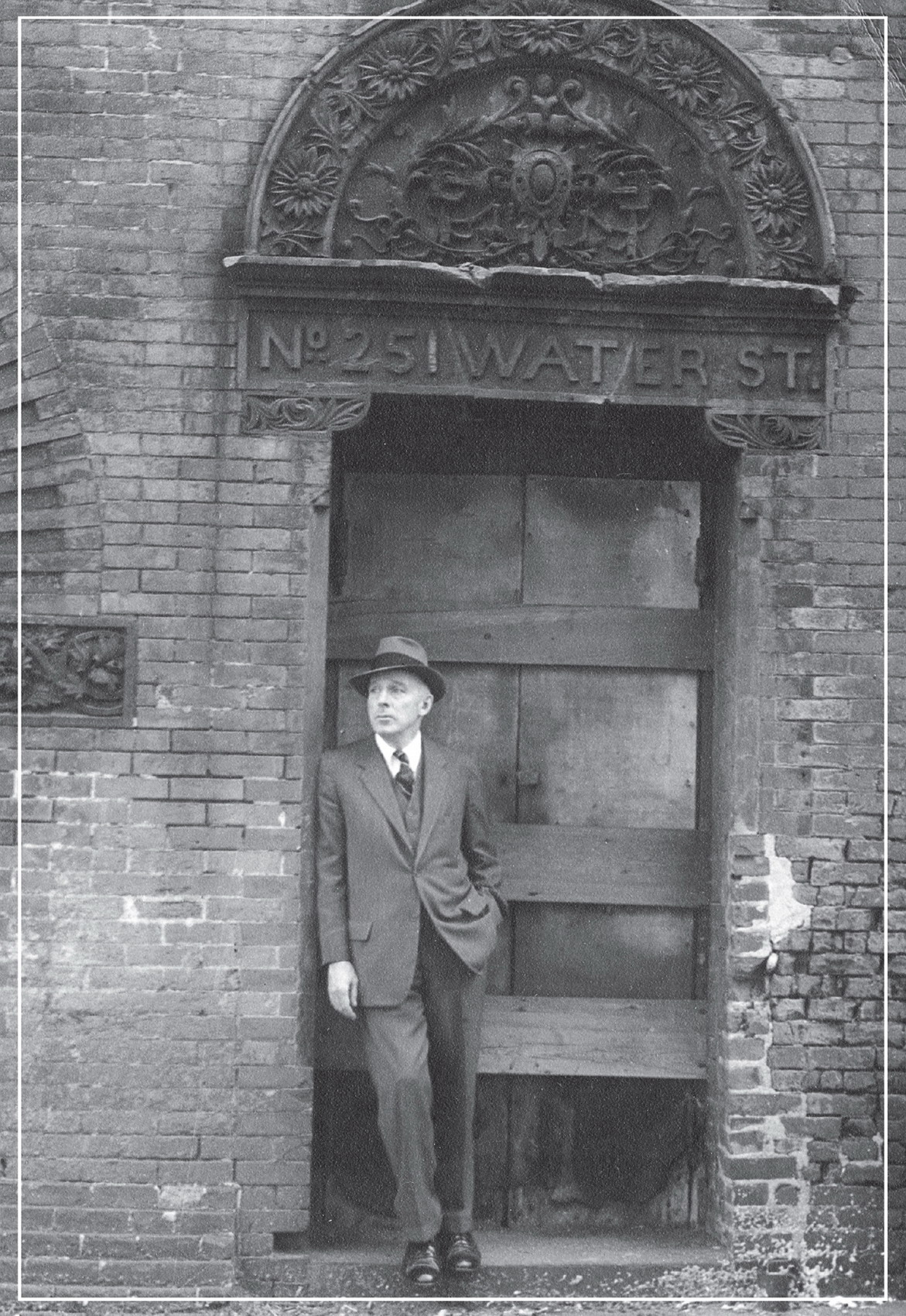

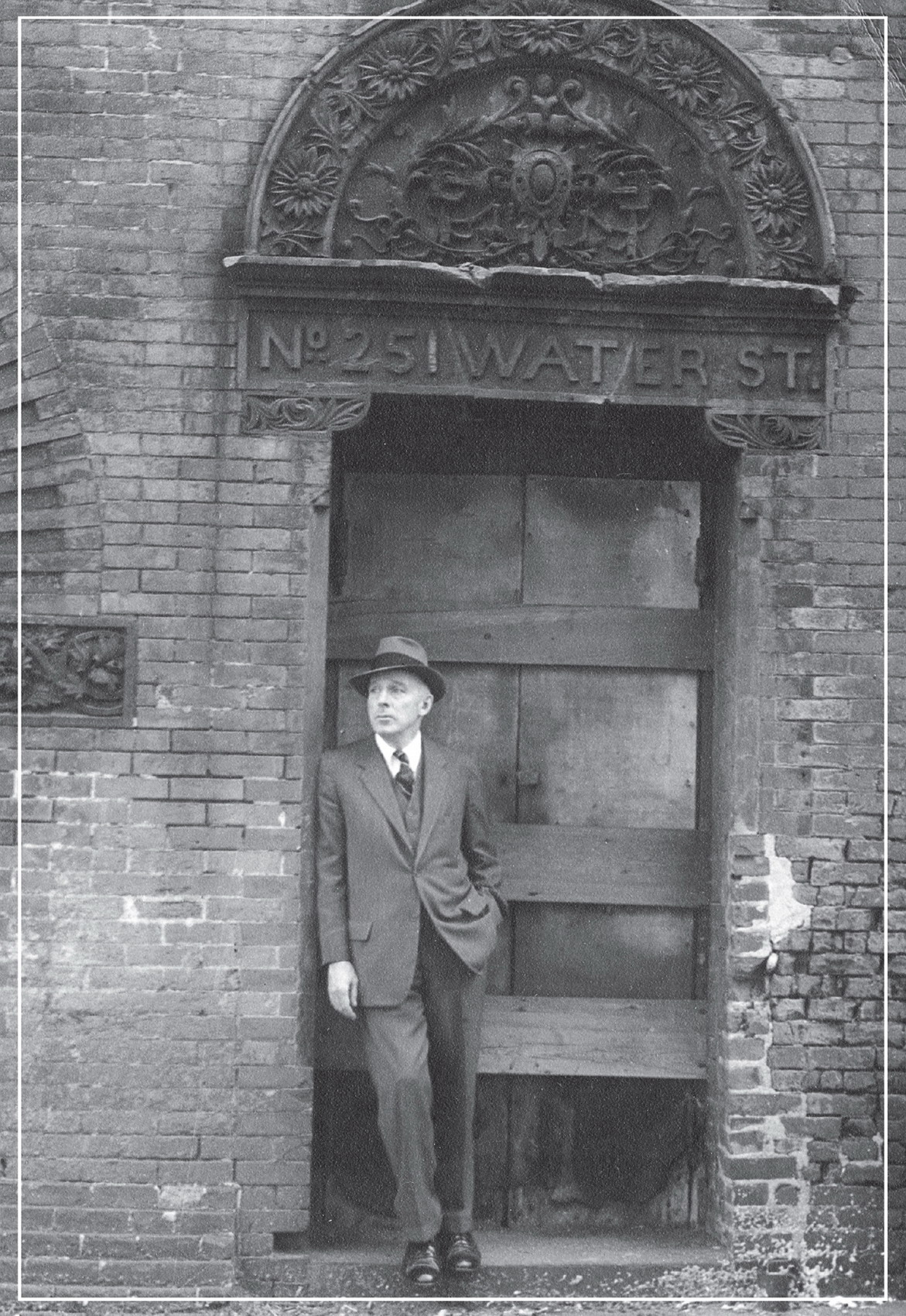

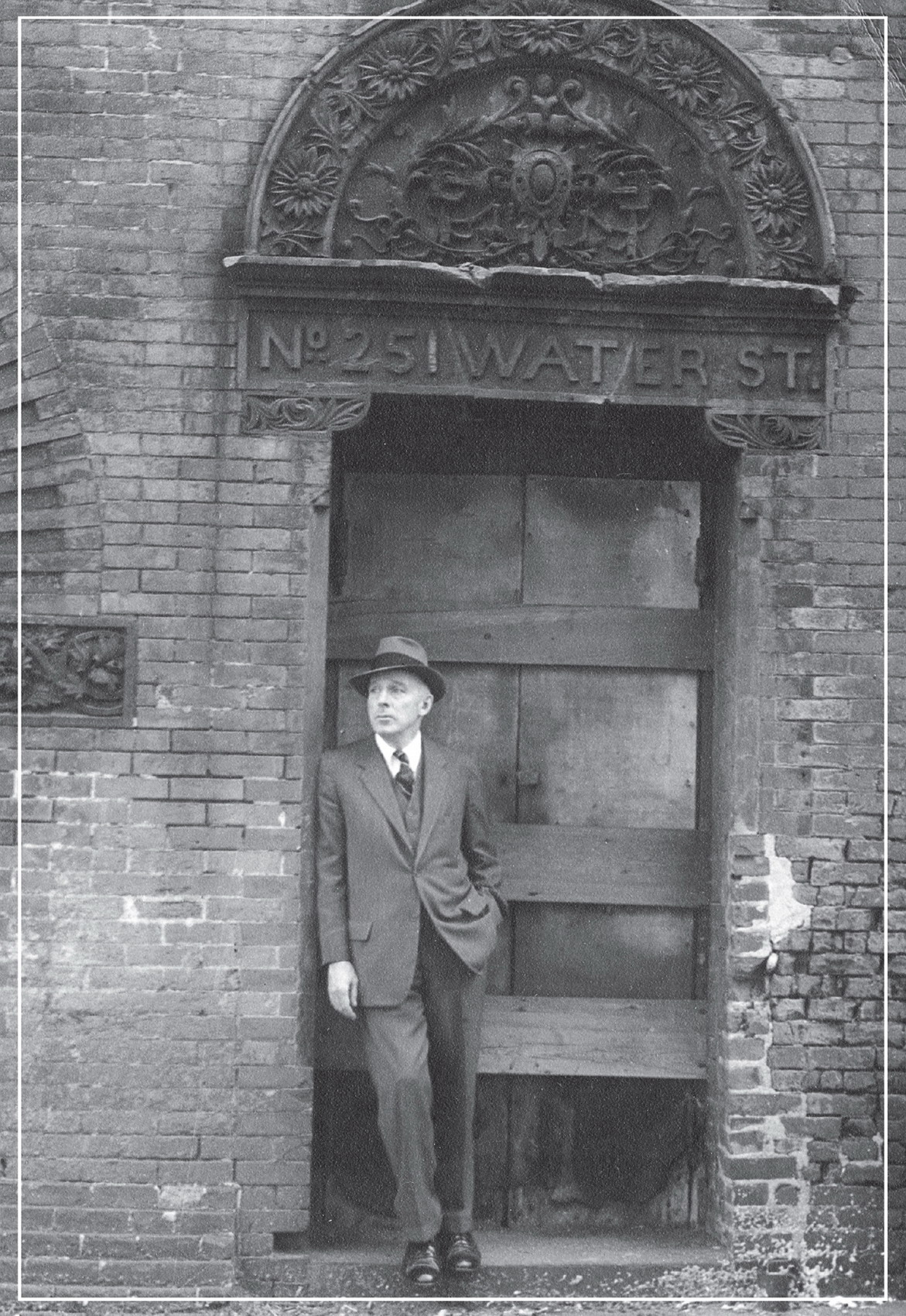

Frontispiece: Photo by Therese Mitchell

eBook design adapted from printed book design by Barbara M. Bachman

Cover design: Joseph Perez

Cover image: from an illustration by Thomas Ehretsmann

v4.1

a

For Deb,

more than ever

Every portrait that is painted with feeling is a portrait of the artist, not of the sitter.

Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

THE WONDERFUL SALOON

Throughout his life Bills principal concern was to keep McSorleys exactly as it had been in his fathers time. When anything had to be changed or repaired, it appeared to pain him physically. For twenty years the bar had a deepening sag. A carpenter warned him repeatedly that it was about to collapse; finally, in 1933, he told the carpenter to go ahead and prop it up. While the work was in progress he sat at a table in the back room with his head in his hands and got so upset he could not eat for several days. In the same year the smoke- and cobweb-encrusted paint on the ceiling began to flake off and float to the floor. After customers complained that they were afraid the flakes they found in their ale might strangle them to death, he grudgingly had the ceiling repainted. In 1925 he had to switch to earthenware mugs; most of the pewter ones had been stolen by souvenir hunters. In the same year a coin-box telephone, which he would never answer himself, was installed in the back room. These were about the only major changes he ever allowed.

From The Old House at Home, 1940

T he low, late-afternoon sun fills the front of McSorleys wonderful saloon with light the same color as the ale theyve been dispensing here since before the Civil War. Even at this quiet hour, laborers from the East Village, NYU students, and a few stray sightseers fill most of the tables and the stools along the (again) sagging bar, across the top of which is carved the legend B E GOOD OR BE GONE . About half the patrons are women, a fact that would have dismayed Old John McSorley, the taverns founder and namesake, who enthusiastically enforced his male-only policy, to the point of personally showing bolder offenders the door. But progress nudges even landmarks, and McSorleys Old Ale House is one of New Yorks most venerable. It has been operating here, on East 7th Street just off Cooper Square, longer than any other tavern in the city.

Now a trim, erect man walks in to the tavern, bringing with him a bit of the seasons chill air. He removes his coat to reveal a smartly tailored Brooks Brothers suit, white shirt, and dark tie, all topped with a handsome fedora. He hangs the coat on a hook and takes a seat at a table near the back wall. At age seventy, he has the look of a much younger man, made all the more attractive by a small smile that he usually gets when he is back at McSorleys. He is, in a word, exactly what people have in mind when they call a man dapper.

The elegant patron is the writer Joseph Mitchell, who has lived just a few short blocks from McSorleys since he moved to Greenwich Village in the early forties. It is late autumn of 1978, although because this is McSorleys it might just as well be 1878. He orders a tall mug of aleat McSorleys you can have light or dark, your only two choices of the house specialty, although they also have porter and stout. McSorleys has never been big on choice, or change. The presence of women, in fact, is about the only accommodation the place has made to a postmodern age (and to its court rulings frowning on gender discrimination, even in quirky saloons). Certainly McSorleys is much as it was in 1940, when Mitchell immortalized it in the pages of The New Yorker magazine. The same wavy plank floors are still slick with sawdust. Generations of names are carved into the same oaken tabletops. The same dust, only thicker, coats the same gaslight fixtures and firemens helmets and stopped clocks. Crowding the walls above the wainscoting are photographs of the same cops and pols and sports heroes, mostly Irish, all as dead as the New York they belonged to.

Mitchell watches the young man at the bar expertly draw another mug of ale, and he considers the establishments unbroken chain of Irish ownership. Old John McSorley opened it back in 1854 and was its sole proprietor until 1890, when he made his son, Bill, the head bartender. Bill took over in 1910 when the old man died. In 1936, Bill sold McSorleys to a friend, Daniel OConnell, and it would remain in OConnells extended family for several generations until just the past year, when it was sold to Matthew Maher, yet another Irish immigrant who had worked at McSorleys for fourteen years before taking it over. On this lazy afternoon Mitchell appears to be nursing a drink, but what he really is doing is watching, and listeningalways listening. He overhears snippets of conversation off to one side or another, and once in a while, maybe catching a well-turned phrase, he removes a folded piece of paper from his jacket and makes note of it. (His note-taking regimen has never changed: Before he goes out for the day, he takes a piece of New Yorker copy paper, folds it in half, then neatly folds it again into thirdsthe perfect size to slide in and out of a coat pocket, where he also keeps his ever-ready pencil.) In other words, Mitchell is doing precisely what he did back in 1940hanging out, becoming a McSorleys fixture himself, until the language, rhythms, and lore of the place are second nature and ready to be carried to the page.