Contents

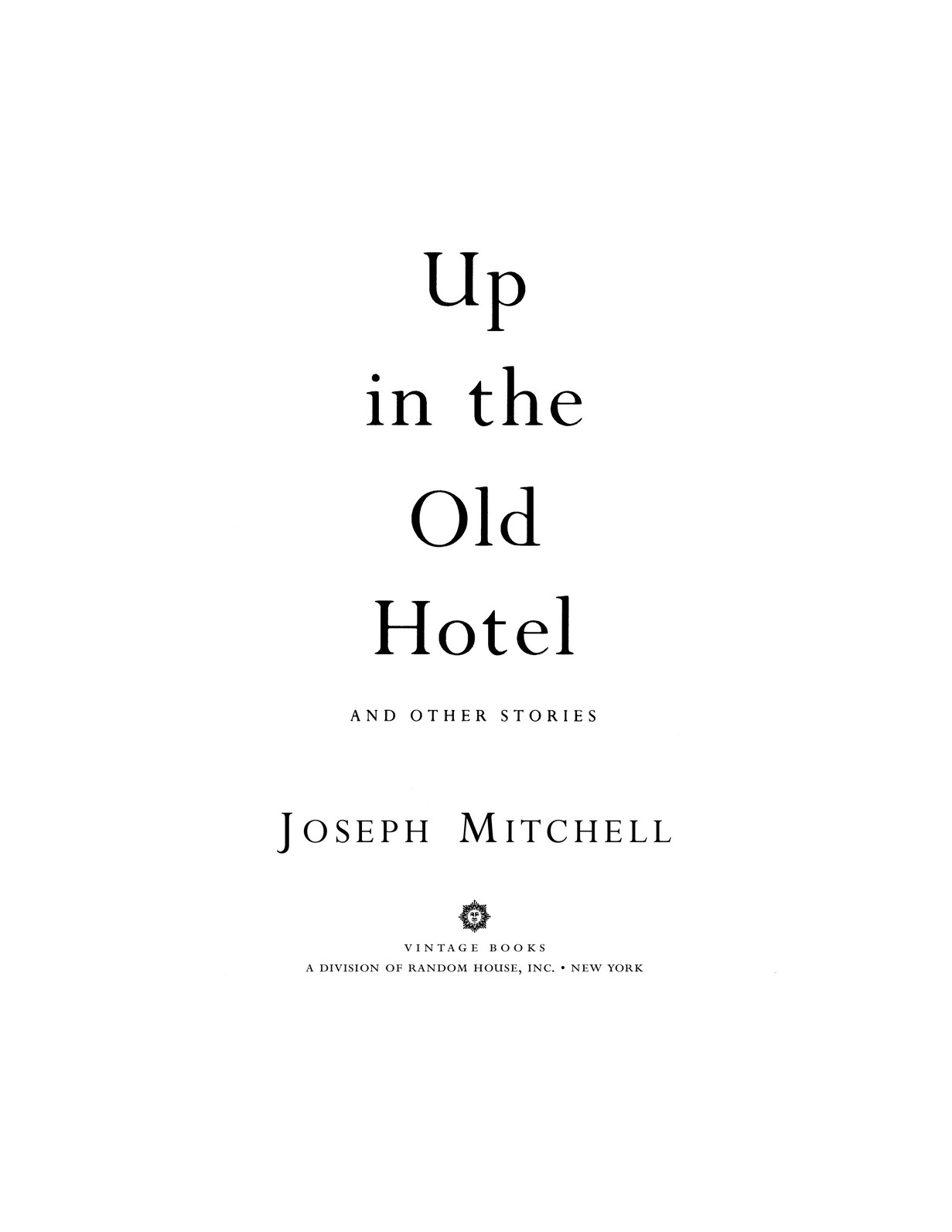

J OSEPH M ITCHELL

Up in the Old Hotel

Joseph Mitchell came to New York City from a small farming town named Fairmont in the swamp country of southeastern North Carolina in 1929, when he was twenty-one years old. He worked as a reporter and feature writerfor The World, The Herald Tribune, and The World-Telegramfor eight years, and then went to The New Yorker, where he remained for the rest of his career. Mitchell died in 1996.

BOOKS BY JOSEPH MITCHELL

My Ears Are Bent

McSorleys Wonderful Saloon

Old Mr. Flood

The Bottom of the Harbor

Joe Goulds Secret

Up in the Old Hotel

VINTAGE BOOKS EDITION , JULY 2008

Copyright 1938, 1939, 1940, 1941, 1942, 1943, 1944, 1945, 1947, 1948, 1949, 1951, 1952, 1955, 1956, 1959, 1964, 1965, 1976, 1992 by Joseph Mitchell Copyright renewed 1966, 1967, 1968, 1969, 1970, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1976, 1977, 1979, 1980, 1983, 1984, 1987, 1992 by Joseph Mitchell

Introduction copyright 2008 by David Remnick

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover in the United States by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, in 1992.

Vintage and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

The stories in this book were originally published in a somewhat different form in The New Yorker.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Saul Steinberg for permission to reprint several illustrations. Copyright 1951, 1964, 1979, 1992 by The New Yorker Magazine, Inc. Reprinted by permission of Saul Steinberg.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mitchell, Joseph, 19081996.

Up in the old hotel and other stories / Joseph Mitchell.1st Vintage Books ed.

p. cm.

Originally published in a somewhat different form in The New YorkerT.p. verson.

ISBN 978-679-74631-7

1. New York (N.Y.)Fiction. 2. New York (N.Y.)Social life and customs. I. Title.

[PS3525.I9714U6 1993]

813.54dc20 92-50835

eBook ISBN9781101971307

v4.1

a

F OR S HEILA M C G RATH

Contents

Introduction

J OSEPH M ITCHELL TRAINED AT NEWSPAPERS that are now extinct in a city that is forever lost. In October 1929, just as the Great Depression struck, Mitchell left his home in North Carolina and arrived at Pennsylvania Station. He was twenty-one. He quickly made a name for himself in New York as a reporter at the Morning World, The Herald Tribune, and The World-Telegram. As a feature writer, police reporter, and rewrite man, he covered the Lindbergh kidnapping trial and countless fires and murders. He interviewed flea-circus operators, Central Park cave dwellers, oystermen, ship captains, fan dancers, Clara Bow, Fats Waller, Albert Einstein, and the Queen of the Nudists, who received the young Mitchell in naught but a blue G-string. Mitchell possessed a gift for human and reportorial listeninga natural sympathyequal to his gift for prose. Ear benders he called his favorite subjects.

Mitchell became one of the most popular newspapermen in the city. His picture appeared on the sides of delivery trucks. He was nimble, quietly ambitious, and infinitely curious. If he wanted to know a neighborhood better, he would take up residence there in a cheap rooming house. He was incredibly fluent and energetic. As he once recalled of his newspaper days, it was not unusual for him to report and write three features in a single day:

When I came in one morning at nine I was assigned to find and interview an Italian bricklayer who resembled the Prince of Wales; someone telephoned that he had been offered a job in Hollywood. I tracked him to the cellar of a matzoth bakery on the West Side, where he was repairing an oven. I went back to my office and wrote that story and then I was assigned to get an interview with a lady boxer who was living at the St. Moritz Hotel. She had all her boxing equipment in her room. The room smelled of sweat and wet leather, reminding me of Philadelphia Jack OBriens gym on a rainy day. She told me she was not only a lady boxer but a Countess as well. I went back to the office and wrote that story and then I was assigned to interview Samuel J. Burger, who had telephoned my office that he was selling racing cockroaches to society people at seventy-five cents a pair. Mr. Burger is the theatrical agent who booked such attractions as the late John Dillingers father, a succession of naked dancers, and Mrs. Jack (Legs) Diamond. He once tried to book the entire Hauptmann jury. I found him in a delicatessen on Broadway where he was buying combination ham and cheese sandwiches for a couple of strip-tease women.

By 1938, The New Yorker had weathered its early financial struggles, and its founder and editor, Harold Ross, himself a newspaperman from the provinces, added to his staff by hiring Mitchell, thinking, no doubt, that he could use not only the young mans evident skills but his impressive productivity. Mitchell remained a staff writer at the magazine for fifty-one years. His most prolific year was 1939, when he had thirteen bylines, and he kept up a similar pace for several years thereafter. The result was the first of his books, McSorleys Wonderful Saloon, a series of New York narratives and character studies as pointed, various, and haunted as the stories in Dubliners.

Mitchells preferred precincts included Times Square, the Village, the East Side saloons, Harlem, and, perhaps most of all, docks and piers. He was not much interested in the good and the great. As he had been in his newspaper work, he was drawn to the visionaries, obsessives, imposters, fanatics, lost souls, the-end-is-near street preachers, old Gypsy kings and old Gypsy queens, and out-and-out freak-show freaks. But now his work took on a greater depth. The jokiness found in his newspaper piecescollected in My Ears Are Bentdisappeared; the tone is more mature. There are shadows in the rooms, sadness in even the funniest voices. At Rosss New Yorker, Mitchell found his way.

The most prized possession in my office at the magazine is a photograph of two menthe closest of friendswho set the standard for nonfiction writing in their time. It is a photograph of Mitchellslender, dapper, impishand A.J. Liebling, a Rabelaisian character in both girth and spirit, sitting in wicker chairs under a craggy tree in eastern Long Island. The two men are laughing more than is absolutely required for a photographthe result, perhaps, of the empty wine bottles arrayed in front of them. Mitchell and Liebling often shared turf and characters; they were drawn to the marginal men and women who could talkthe fight trainers, the rogues, the telephone-booth Indians. But in language they were as different as Chekhov and Gogol. Liebling wrote quickly, furiously, faster than anyone better, better than anyone faster. His sentences were baroque, arch, full of digressive comedy (except when he was at war, where he was all business). Mitchell was no less funny, but he was precise, haunted, restrained, and exquisite. His colleague Roger Angell once said that Mitchells writing stood firmly and cleanly in your mind, like Shaker furniture.