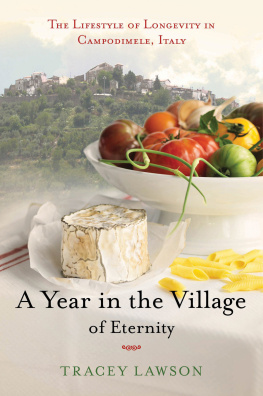

For my parents, Joan and George Lawson

To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven...

Ecclesiastes 3:1

Contents

Come to Campodimele in the spring, in the early morning, when the air is still cool, though the sun is spilling over the Aurunci peaks.

Youll find the village at the end of the mountain road, which twists like a serpent through the wooded crags and the tunnels of newly green trees.

Park up near the statue of San Padre Pio, where the village starts, and if you glance back for a moment the way you came, youll see the last twists of mist playing on the valley floor.

Now take the fork in the road that leads uphill behind the village the one where the stone hen houses sprawl. Chances are youll meet some of the people who feature in this book.

Perhaps Gerardo, zipping past on the aged scooter hes been riding for so many of his seventy-nine years. Or Maria, chasing her hens up the hill on her eighty-three-year-old legs. Or Archimede, who fills his retirement with regular 7 kilometre runs on mountain paths.

Continue uphill and youll find the eleventh-century walls that encircle the borgo , the medieval heart of Campodimele. Ahead is a covered alleyway that cuts through the walls, and if you dip into its centuries-old shadows then out again, youll emerge onto the old piazza. Here stand houses several storeys tall, reached by staircases made of stone, wreathed in red geraniums which tumble from terracotta pots. Already the front doors are open, and the cooking aromas of garlic, basil and sweet tomatoes are singing on the breeze.

Walk past the house with the mural of the Virgin Mary and follow the curved steps down and round, and below is the main piazza I think youll pause at the top of the stone stair to drink in the vista that tumbles off the edge of the square, down to the Liri Valley and towards the Tyrrhenian Sea.

If its Wednesday, which is market day, you might bump into Assunta, whose brilliant eyes belie her seventy-three years, perhaps buying oranges brought up from the citrus groves of neighbouring Fondi. Or off to forage edible greens in the surrounding fields. Or Adalgesia, for whom market day is more of a social event, because even now, in her seventies, she grows almost all her familys food.

These are just a few of the people Ive met in Campodimele, the Italian village that welcomes visitors with a signpost bearing its sobriquet: Il Paese della Longevit , The Village of Longevity.

Others, including scientists and medics, have been known to refer to Campodimele as Il Paese dellEterna Giovinezza The Village of Eternal Youth or, as I prefer to think of it, the Village of Eternity.

The reason? The people of Campodimele boast levels of good health and life expectancy which have attracted the attention of doctors both in Italy and further afield.

According to the Comune di Campodimele, 111 of the 671 people who live in the village are between 75 and 98 years old, the age of the oldest person who has residency there. That is to say, 16.6 per cent of the population is over seventy-five, as I write these words. The Communes most recent statistics, calculated in 2009, find that the average life expectancy of both men and women is ninety-five. That compares to the Italian average of 77.5 years for men and 83.5 years for women, and a European Union average of 75.6 years for males and 82 years for females. Campodimele has been home to an unusual number of centenarians.

It was reports like these which first brought me to Campodimele. At the time, I was a newspaper journalist in the UK, researching an article on foods which might help promote longevity. I kept finding references to an Italian village I had never heard of before.

The more I read about Campodimele, the more fascinated I became. Scientists had found unusually low blood pressure and cholesterol levels in many of its elderly residents; the World Health Organization had investigated the village under the auspices of its Project Monica, which studied communities around the world to monitor trends in cardiovascular disease.

More than these findings, I was intrigued by the descriptions of the villagers and their daily lives. Journalists who visited Campodimele portrayed the elderly residents as unusually vigorous for their ages pensioners who rode pushbikes, herded goats in the mountains, worked in the fields from dawn til dusk, growing almost all their own food. Reporters told how octogenarian men whiled away sunny afternoons playing cards under the elm tree in the piazza while their womenfolk gathered at the hen houses, collecting their suppers of freshly laid eggs.

Levels of heart disease, obesity and cancer were, I read, relatively low in Campodimele.

These people, it seemed, could not just expect to live lives longer than many in Europe. More significantly, in my opinion, they appeared to be able to look forward to a healthier and more active old age than many people in the UK.

Reading about Campodimele from the chaos of my city-dwelling commuters life in the UK, I longed to sit on the village piazza, sipping espresso beneath its 300-year-old elm tree, enjoying something of the lifestyle which helps these people live so well. Because, as the Irish satirist Jonathan Swift once wrote, Every man desires to live long, but no man would be old.

And so, in the autumn of 2006 I jumped on a plane to Rome and drove 160 kilometres south along the breakneck autostrada and the squiggly mountain roads of Lazio to investigate for myself.

I knew so little about the village then. Situated midway between Rome and Naples, it was about thirty minutes from the coast, in the province of Latina. Teetering on a promontory within the Aurunci Mountains National Park, it was 647 metres above sea level. This much Id gleaned from the local councils website.

The rest of my imaginings were inspired by my youthful travels in the north of Italy and that peculiar brand of romanticism with which the English view Italian life a gilded vision of pasto ral utopias and culturally rich cities fuelled by the writings of E. M. Forster, D. H. Lawrence and Goethe. The villages very name is evocative it derives from the Latin campus mellis , field of honey, for this is the region which cultivated the bees that brought honey to the tables of the Roman Empire.

Arriving in Campodimele, I did indeed discover the archetypal Italian rural idyll: a cluster of stone houses perched high on a sun-drenched mountain top; narrow, winding streets encircled by turreted medieval walls; an eleventh-century church with a soaring bell tower; and a piazza with a truly breathtaking panorama across the valley below. And, all around me, evidence of what had brought me there elderly farmers clambering over olive groves; old women mounting ladders to cut grapes from pergola vines; grandmothers striding up steeply stepped alleyways while balancing bundles of kindling on their heads. I also met one gentleman of 103 years, sitting down to minestrone soup for lunch.

Greeting me in his office at the apricot-coloured town hall, Generale Aldo Lisetti, then mayor of Campodimele, told me he believed that various factors support the health and longevity of the constituents, including the pure mountain air and relatively low stress levels of rural life. Perhaps, he pondered, some residents even enjoy a genetic predisposition to long life. But, like all the other villagers I spoke to, he agreed that there is another factor: diet.

Fresh, seasonal and chemical-free fruit and vegetables, said Lisetti. Only a little meat and fish. And simply cooked at home. This is the part of the equation that most interested me, the factor that had led me to trip upon Campodimele in the first place: what people here eat.

Next page