Table of Contents

PENGUIN BOOKS

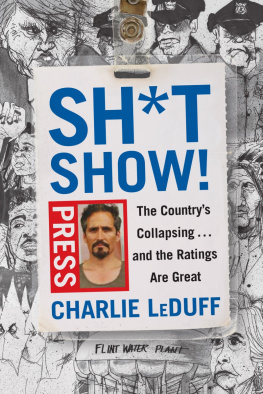

WORK AND OTHER SINS

Charlie LeDuff contributed to the 2001 Pulitzer Prizewinning New York Times series How Race Is Lived in America, and has also received a Meyer Berger Award for distinguished writing about New York City. He has been a staff reporter at the Times since 1999 and is now a member of the Los Angeles bureau. He lives with his wife in Hollywood, California.

ALL MY RELATIONS

The word newspaper-writer means, at the very least, a scoundrel. I am one of them. I work with them. I shake hands with them. Im even told Ive begun to look like one. But I shant die as one.

ANTON CHEKHOV

INTRODUCTION

Among the more fantastic nobodies hanging from my family tree are a pair of heavy-drinking lighthouse keepers, a sleepy morphine addict, a grave robber, a rumrunner, a streetwalker, a numbers maker, a dean of a sham college and a police informant. A few of these relatives are still living, a few lived long lives, a few died young by misadventure or of self-neglect. Those are sad biographies ending with done me wrong.

My grandpa Roy was the bookmaker for the Detroit Race Course, which no longer stands. Like everything else, it has been replaced by a shopping mall, I think. They say Grandpa was a math genius. Maybe, but he never struck me as one. He was a sharp dresser with a thin pencil-trim mustache, a sophisticated and sociable man, but a math genius? I cant say. He did make a lot of money in his time, but when the president of the Teamsters and the underboss of the Bufalino family were your dinner pals, you didnt really have to be that good with the numbers.

Grandma insists that Grandpa was not a gangster but the most decent and honorable man she had ever met. I believe her, but I wonder why she kept the photos of Grandpa and Jimmy Hoffa at the bottom of the trunk, above the one of Grandpa and a strange woman laughing it up in a fishing cottage somewhere far away. I am working from memory here, since relations of mine stole that trunk and most of the rest of my grandmas things and sold them away to strangers.

But this is not a memoir. There are too many of those. I give you some family background as a way of credentialing myself, to show you that everybodys got a history, that most everybody comes from nowhere and that in every family there is a cousin no one wants to admit to. This book is about such people: New Yorkers almost exclusively, working people most definitely.

The dandies I know say I write about dives and losers, but they are wrong. I write about the people who live in neighborhoods, crowded apartments and dreary ranch houses. These are the people who shovel their own snow and have fat aunties who wear stretch pants with stains on the ass. This is not a book about the people who have doormen but a book about doormen. It is about the laborer, the dreamer, the hustler, the immigrantwhether he is a writer from Michigan or a waiter from Michoacn. I suppose in all of this Im trying to find myself and justify him, to you.

When the cocktail set tells me they enjoy the cast of losers, I never mind them. I smile and drink their liquor. They dont know work.

The elders in my family told me our stories. The better stuff has come more recently, pried out with the crowbar of old age. Nobody likes to admit he cheated his way to the middle. As far as I know, our stories of half-breeds, half-asses, half-truths, crawdaddies from the Louisiana swamps and kicking birds from the Great Lakes have never been written down or chronicled except for that newspaper photograph of Grandpa and Jimmy Hoffa standing on the picket line in front of the track two generations ago.

That picture, that one piece of acknowledgment and notoriety, is lost to my family The stranger who bought the trunk has no idea that the thin man standing next Hoffa was known along Woodward Avenue as the Duke.

That American nobody is somebody to me. Hes the guy who taught me about horses. You will not find recollections of him in these pages, but he is here. Pete the Gambler and I spent hours at the Aqueduct Race Track in Ozone Park, Queens, talking about my grandpa, about his handicapping system and his philosophy on horses. That philosophy: Stay away from the track. But it doesnt work that way and so there you have it.

The nice thing about being a reporter is that you can show a gravedigger your press card and ask him: You mind if I watch? He lets you watch for a while. He will let you try his shovel until your hands start to blister and your back starts to ache. You hand him back his shovel and you watch some more and it dawns upon you to ask, Doesnt that hurt your hands and back? Usually, people try to make their lives sound better than they are. But that falls away after a while, and the longer you hang around, the less they realize youre around and eventually you get at it.

Reporters like to tell themselves that they are doing something socially and culturally important and that in the best of circumstances they are doing some goodrighting wrongs, exposing crooks and such. Thats what they tell each other over free drinks at the awards ceremonies, anyway.

The truth is, we reporters are window peepers, suck-ups, people too ugly for the movies. Thats what normal people say. Thats the bad part. The good part is the job beats manual labor.

The stories in this book appeared in The New York Times at around the turn of the century. Chronologically, they end with September 11 and its aftermath. I wrote some stories about Squad 1, a firehouse in Brooklyn that lost half its men. Rereading them now, these stories seem salty and cold to me, like watering eyes in the win tertime. There was so much more to be said, but I could not say it, because life in those moments was hard enough. I hope the stories at least seem limber, that something good can be gotten from them by somebody.

New York is a glamorous city, constituted mostly of nobodies. They crave the lights, and if they tell you differently, theyre lying. Only dreamers come to New York. As a matter of course, few people have control of their lives. You live at the whim of your boss, your landlord, your grocer, the stranger, the judge, the bus driver, the mayor who wont let you smoke. On the other hand, you live at the whim of your whims, and that is the most exciting thing there is.

New York is a lot like a shit sandwich. The more bread you have, the less shit you taste, and this town would tumble to the ground without money. For those who dont have it, there is always the hope of getting it. This book is meant for them.

WORK

WHEN I WAS a cub reporter at the Times, I was talking with an editor about a strike at an auto-parts plant in Flint, Michigan. There was some story in the paper that day about workers who were spending their idle time antique shopping and speeding around the lakes in their powerboats.

Since when is it bad to have a boat and make good money? I asked.

The editor, a smart guy with a weak chin, put his palm to his nose and said: Those people had about this much foresight. They should have seen the writing on the wall and gone to college.