Once again Jim Leeke gives us kids in the grandstands our fifty cents worth. From the Dugouts to the Trenches has the reader tugging Jims jersey and begging, Say, mister. Got any more of them swell stories?

A first-rate contribution to baseball and Great War scholarship.

Leekes trenchant look at baseball during the Great War describes grandees, players, and journalists struggling to find a footing in the suddenly hobbled game. Meanwhile, their colleagues overseas witness the grim dawn of the modern world. Riveting and insightful.

L. M. Sutter, author of Arlie Latham: A Baseball Biography of the Freshest Man on Earth

From the Dugouts to the Trenches

Baseball during the Great War

Jim Leeke

University of Nebraska Pres | Lincoln & London

2017 by Jim Leeke

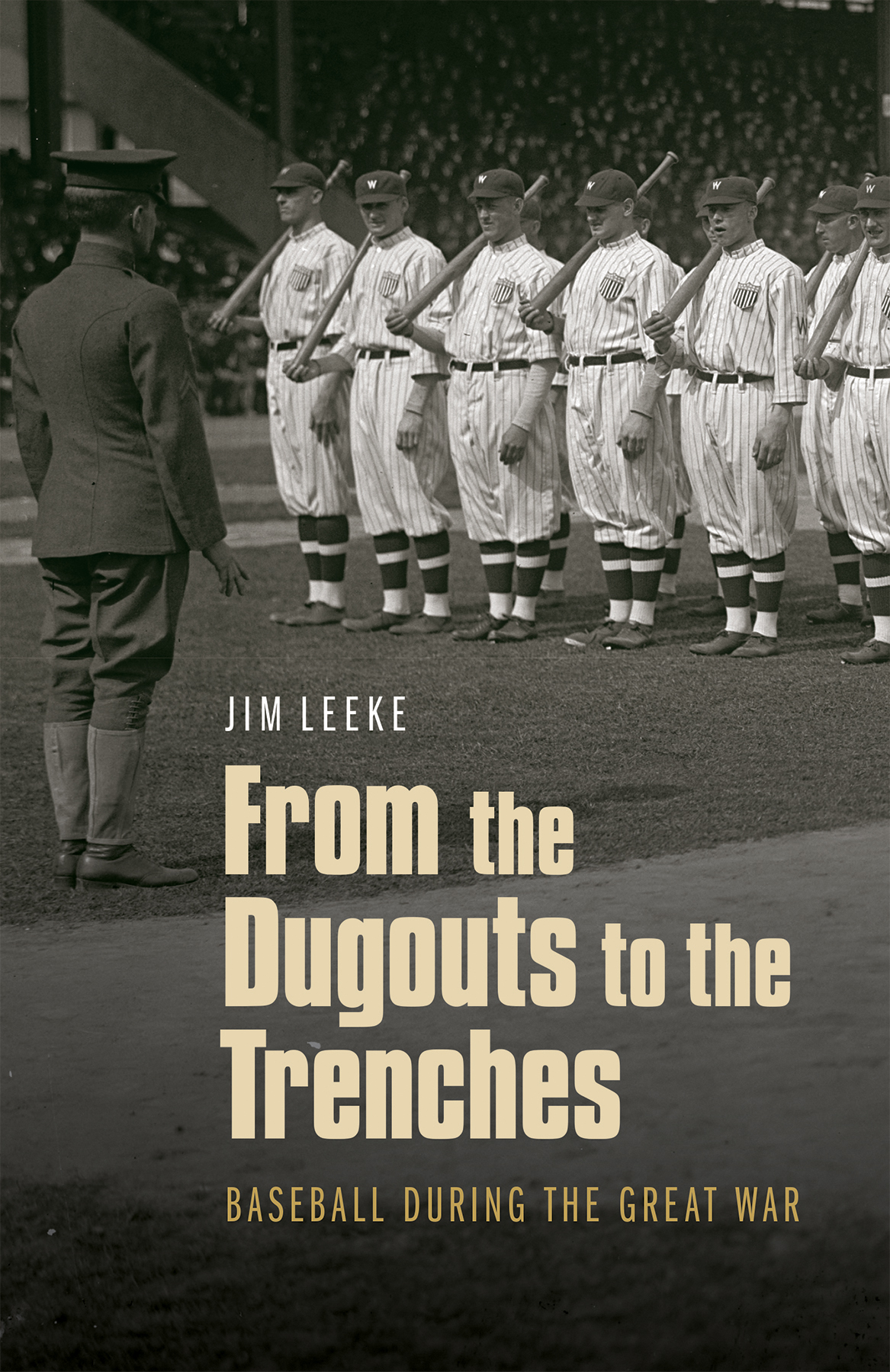

Cover designed by University of Nebraska Press; cover image is from the interior.

Author photo courtesy of George C. Anderson.

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Leeke, Jim, 1949 author.

Title: From the dugouts to the trenches: baseball during the great war / Jim Leeke.

Description: Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016053349 (print)

LCCN 2017005366 (ebook)

ISBN 9780803290723 (hardback: alk. paper)

ISBN 9781496201614 (epub)

ISBN 9781496201621 (mobi)

ISBN 9781496201638 ( pdf)

Subjects: LCSH : BaseballUnited StatesHistory20th century. | Baseball players as soldiersUnited States. | World War, 19141918Influence. | BISAC : SPORTS & RECREATION / Baseball / History. | HISTORY / Military / World War I.

Classification: LCC GV 863. A 1 L 35 2017 (print) | LCC GV 863. A 1 (ebook) | DDC 796.357097309041dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016053349

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

In memory of

Harry and Vada Beebe

and Leonard Koppett

dugout: A shelter dug out of a hillside; specif., a cave, the side of a trench, etc., often roofed with logs and sod, for storage, protection, etc. Baseball. A low shelter containing a players bench and facing upon the diamond.

Websters Collegiate Dictionary, 1942

Contents

America wasnt prepared for war in the late winter and early spring of 1917, but it certainly was ready for baseball. The Boston Red Sox were the reigning world champions, the best of sixteen Major League clubs scattered through the Northeast and out to the Midwest as far as the left bank of the Mississippi River. Below the big leagues, twenty-two Minor League clubs were set to play ball in parks across the country, from the biggest in Class AA to the smallest in Class D . Together, these many leagues comprised Organized Baseballthe national pastime, the summer game, employment for thousands, entertainment for millions, a hardscrabble business of sharp elbows, big egos, promise, failure, and reward. What would happen if war came?

Capt. T. L. Huston, co-owner of the New York Yankees, thought he knew. Perhaps before any teams go to their training camps we will have a chance to see whether the players are as loyal to their country as to their [players] fraternity, Huston said.

Harry Frazee, who owned the Boston Red Sox, thought he knew, too. People want to get away from the war topics, and almost any kind of diversion to take their minds from the situation is welcome, Frazee said. What can fit this need better than baseball?

Both men were right, if not at the same time. America entered the war that April and nothing much changed right away, as Frazee expected. Flags flew, rhetoric soared, and the baseball season began as usual in the Major and Minor Leagues. Then as America armed and readied for battle, Organized Baseball increasingly felt the strain of the vast European war, as Huston expected. So much changed that within eighteen months the Major Leagues were scarcely recognizable. Every Minor League but one had shut down, and the World Series was a shambles. How and why did this occur? What happened to the ballplayers? Does it all still matter, a hundred years on?

In quieter times, the first two questions might have been answered a quarter century or so after the events, when ballplayers and historians naturally looked back on their lives and times. But by then, America was fighting the Second World War, and no definitive history of baseball during the previous war was written. Any history produced today has a different, less personal perspective. Details come not from participants living memory but largely from newspaper microfilm and digital archives, from old front pages and sports sections, and from many hundreds of columns and game stories and dispatches from France. The endeavor to find these pieces is itself entertaining and enlightening. Along the way, answers to the third question begin to emerge. Lets begin with spring training.

Sergeants

In March 1917, with his country on the verge of entering the war in Europe, Sgt. Smith Gibson unexpectedly became one of the most famous soldiers in the U.S. Army. Gibson ran the recruiting office in Macon, Georgia, the spring-training home of the American League New York Yankees. Macon was only about 125 miles from Gibsons hometown of Opelika, to the west across the muddy Chattahoochee River in Alabama. During seventeen years in uniform, the sergeant had never received orders quite like those that had just arrived. He was to become the Yankees new military drill instructoramong the first, so far as anyone knew, ever in the history of Organized Baseball. Soon all eight teams in the American League, plus two in the National, would have drillmasters, too.

A country boy who knew little about big cities, Sergeant Gibson could thank a prominent New Yorker for his new job in baseball. Capt. T. L. Til Huston, the Yankees co-owner, was energetically pushing what newspapers up north called his pet scheme for military preparedness in baseball. In late February Huston and the sergeant had sat down for a chat in Macon. Gibson had said he was willing to drill the Yankees, if and when Huston could get him permission from the War Department. The magnate had promptly fired off a telegram to Maj. Halstead Dorey, a baseball fan serving on the staff of Maj. Gen. Leonard Wood at Governors Island in New York. Dorey had been the guest of honor at a dinner Huston

Although lengthy, the red tape was only a minor hindrance. Regulations prohibited the army from assigning drill sergeants to outside organizations, but nothing prevented a commanding officer from granting furloughs of six weeks to three months to any sergeants whom the league needed. Likewise, the War Department couldnt issue arms to civilian groups, but clubs could buy condemned rifles for drilling. Major Dorey also puckishly warned the Yankees co-owner about an ailment he called rifle arm, which a few sportswriters apparently took seriously. This post-drill stiffness, Dorey said, was likely to appeal to tired pitchers looking for an alibi to avoid work. I would rather have them suffering from rifle arm than from slackers knee, Huston retorted. On February 27 Huston wired Dorey from Macon: