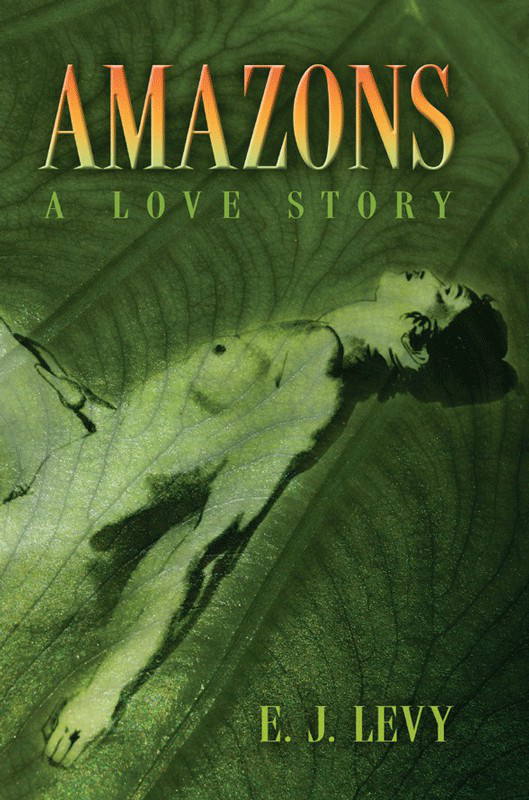

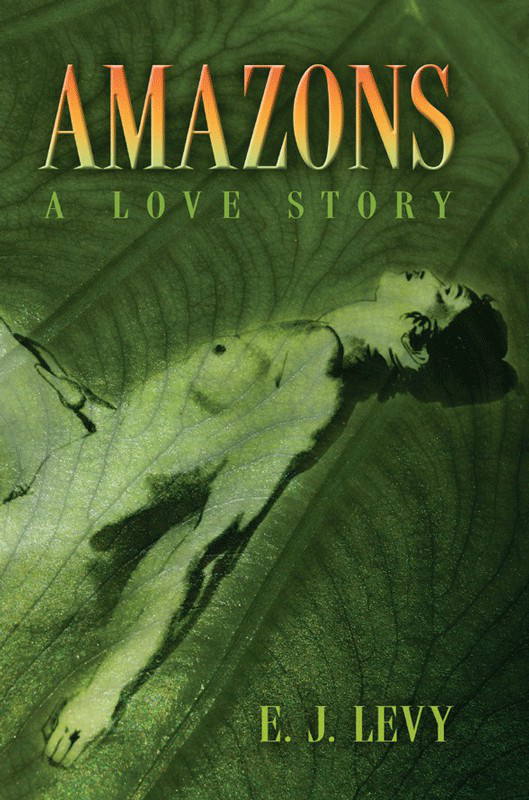

AMAZONS

A Love Story

E. J. Levy

UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI PRESS

COLUMBIA AND LONDON

Copyright 2012 by E. J. Levy

University of Missouri Press, Columbia, Missouri 65201

Printed and bound in the United States of America

All rights reserved

5 4 3 2 1 16 15 14 13 12

Cataloging-in-Publication data available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-8262-1975-6

ISBN 978-0-8262-7277-5 (ebook)

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.

Designer: Kristie Lee

Typesetter: K. Lee Design & Graphics

Printer and binder: Thomson-Shore, Inc.

Typefaces: Palatino and Latino

For Nel

Contents

A modern heroor anti-hero[reflects] an extreme external situation within his own extremity. His neurosis becomes diagnosis, not just of himself but of a phase of history.

STEPHEN SPENDER,

introduction to Under the Volcano

Prologue

The Cartographer of Loss

Imagine the world as flesh.

The southern continents, its meaty flanks. The oceans, its shifting faces. Rivers, veins. Dunes, its soft teats. Like you, it breathes, sighs clouds from steaming rivers, exhales oxygen from the rain forests that gird its distended belly like dispersed lungs. Each leaf, alveolus.

The symbiotic theory of cell evolution maintains that the human body evolved from a composite of relationships of which our organs bear the traces yet; that we are thus not one but many creatures, composed of other unions: symbiotic, parasitic, predator, and prey. This theory (first championed in the nineteenth century and disputed still) maintains that each body carries within it, like the bed of some ancient ocean, a history of microbial cooperation, of species that came together and formed indissoluble bonds. Like the Amazon rain forest, which has evolved slowly over millennia into a complex network of alliance and misalliance, we are each of us a world unto ourselves. Our bodies, like the Amazon, like fate, a built thing.

For a long time I could not think about my tropic life, that year I spent in the Amazon rain forest and in Salvador, Bahia, Brazil. I could not think about the women I knew there, about Nelci and Isa and Barbara, that year during which I tried for months to get to the Amazon, which I had come to study and hoped to save.

Maybe it was fear that held me back from reflecting until now, stopping me from looking back. Fear informed by the memory of a favorite childhood bedtime story, that of Orpheus and Eurydice, read to me in the optimistic late 1960s by my mother, whose optimism like the nations was beginning to wear thin and who sought to instill in us, her three children, in a modest suburb in Minnesota, something of a classical education, the Victorian virtues, by reading to us each night before sleep Greek myths and legends, seeking to pass on to us a faith in gods and mysteries she was no longer able to retain. Weary, without the comforts of cigarettes, which she had given up to give birth to me, without the comforts of her husband who was busy elsewhere, with other women, bored out of her ever-loving brilliant mind, teetering on the brink of suicide, she read to us what seems to me now a fitting tale for her circumstance and for our timethe story of Orpheus seeking to reclaim love from among the ranks of the dead. I learned from my mother and Edith Hamilton never to look back, Orpheus my model for a forward-looking gaze.

Its a familiar story: Orpheus, the lyre player, loses his beloved Eurydice to snakebite. Grieved by her death, he descends to the underworld determined to bring her back to life with him. There he plays for Hades, the king of the dead, who is so moved by Orpheus music that he agrees to release Eurydice on one condition: that Orpheus not look back at her until he reaches the surface of the world. He demands, in effect, an act of faith, a sacrifice to revive what has been lost. Without faith, without sacrifice, Orpheus will lose what he loves. But as he ascends to the surface of the world, Orpheus fails to hear his lovers footfalls on the path behind him and panics; overcome with anxiety, with the need to know, with the need for certainty, he turns around, sees her there, and loses what he loves forever.

Orpheus was granted what no one can really hope to havethe opportunity to revive what has been lost once already. Still we hope. Live recklessly. Bank on being able to bring back what we so casually squander: species brought to the brink of extinction. A world warmed to the edge of melting. But even Orpheus, who was on a first-name basis with the gods, blew it. If we insist on certainty, on an absence of doubt, we too may lose what we best love.

How do we know the world is warming? How do we know what the effects will be of vastly increased levels of CO2? What happens if we fell most tropical moist forests in the course of a single century? We document, sometimes, at the risk of damage, deliberating instead of doing something. Instead of taking action to stem loss or prevent climate change, holding to a path we know to be right, we are tempted to look death in the face, to know for sure what will happen, more afraid of sacrifice for the sake of uncertain reward than of loss, and so risk losing it all. How do we know human activity is warming the world? When we know for certain, will we say, If only we had known?

When I first returned to the United States from the Amazon, I had lunch with my mother. I was home again on some vacation or other, spring break it must have been, and we were eating as we often did in a restaurant that adjoined a local grocery store. It was one of those boastful American grocery stores, with their vast cornucopias of produce and bread and condiments. This particular grocery chain, Byerlys, had made its mark by catering to those who hate to shop. It hung crystal chandeliers above the frozen food aisles; it made its aisles as wide as fashionable boulevards; it dedicated an entire shelf of a block-long aisle to hot pepper sauces; another to pickles from around the world; yet another to varieties of chips; each day it tossed the produce that had not been sold. The stores opulence stood in embarrassing contrast to the place Id left, Brazils impoverished northeast. I dont know if I noticed. Likely its superfluity was comforting.

It was over that lunch that I told my mother that Id been raped in Brazil. Sodomized. She took a stab at her salad, looked at her plate. She said she didnt care what I did, that it was my business, but that she hoped I was using protection. I was not protected against this. I said, Mom, I just told you I was raped and youre talking about condoms? I dont believe this. Thats like my telling you that I tried to slit my wrists and your saying that you hope the blade wasnt rusty. We sat in awkward embarrassed silence for a while. When my mother spoke again, she said that she was sorry, shed thought I was trying to shock her, trying to show her how grown-up I was. I was twenty-two by then, and I was not grown-up. I just knew a lot of things I could not understand yet. A lot of things I rather wished I didnt know about what people are capable of and what they arent.

It would be years before I realized that my mother was merely doing what we all have done, are doing still: she was trying in the face of loss and pain and shock to bring ordinary caution to bear; she was trying to make this reasonable somehow; just as we at the National Institute of Amazonian Research, where I had worked in the Amazon, had done with our maps and charts, our scholarly papers and our studies of rain forest destruction. She was trying to apply the standards of a reasonable discourse to unreasonable acts.

Next page