Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Reyna

God knows how we got through that great mass of water. I advise thee, O great king, never to send Spanish fleets to that cursed river!

FROM L OPE DE A GUIRRES LETTER TO K ING P HILIP II OF S PAIN, 1561

But when death comes I want them to take me and put me in a little boat in this perpetual water between the long shores, and I, down the river, lost in the river, inside the river the river

J OO G UIMAR ES R OSA, A T ERCEIRA M ARGEM DO R IO

It was high noon on July 18, 2014 when our 767 touched down at Eduardo Gomes International, the godfather of all jungle airstrips, cut dead center in the Amazon, and waypoint to a city of 2 million people. Across the tarmac, palms wavered like a mirage through the jet fumes.

I was one of a million sweaty gringos landing in Brazil for the FIFA World Cup. An arctic blast of air-conditioning welcomed the new arrivals to Manaus. In anticipation of the biggest public spectacle in the regions history, the airport was undergoing a $100 million renovation, but like most of the countrys infrastructure projects, it remained in the throes of construction. The terminal smelled of drying paint, some gates boarded over with red Coca-Cola ads spotlighting the gilded World Cup trophy as if El Dorado had at last been found. Beyond the customs check, a pair of tall, sporty women greeted visitors with complimentary mini Budweisers, making themselves available for selfies. The cold brews went down fast on the way downtown, a ride barely recognizable from my last visit eight years earlier when Id traveled to Brazil for the first time to see the country where I was born.

The city had mushroomed like never before. Just beyond the airport perimeter stood a fresh Subway franchise, sandwich artists squeezing sauces on canvases of bread. A recently paved and painted four-lane highway unrolled into the city, flanked by business hotels, night clubs, and love motels. The road led to a knot of overpasses and underpasses, the latest attempt to wrangle the citys notoriously chaotic streets. Trees had been supplanted by billboards: 3G cell phone service, cosmetic dentistry, and home appliances with easy monthly payments. Motorcycles, buses, and American sedans zipped from lane to lane as if testing the asphalt for imperfections.

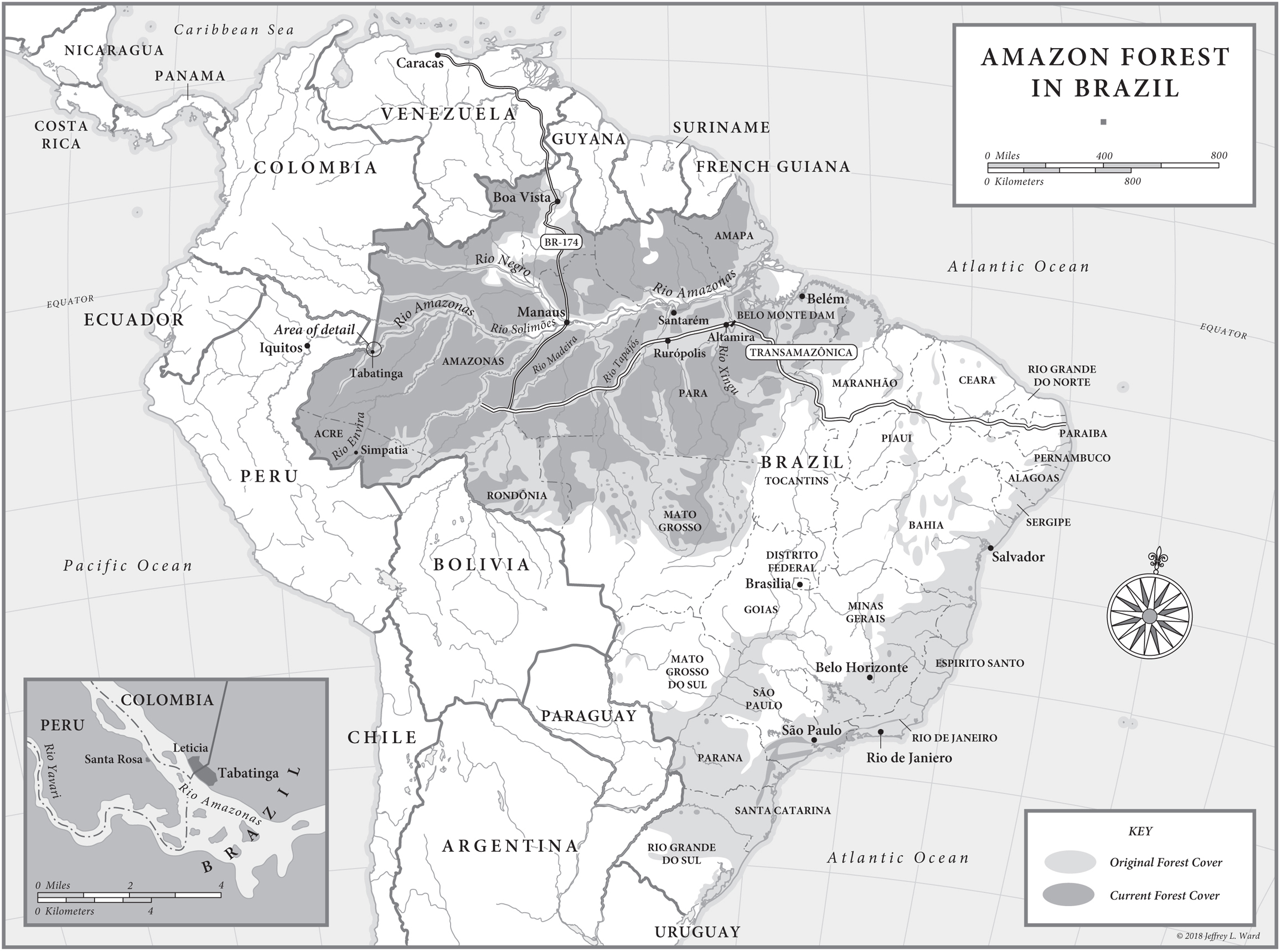

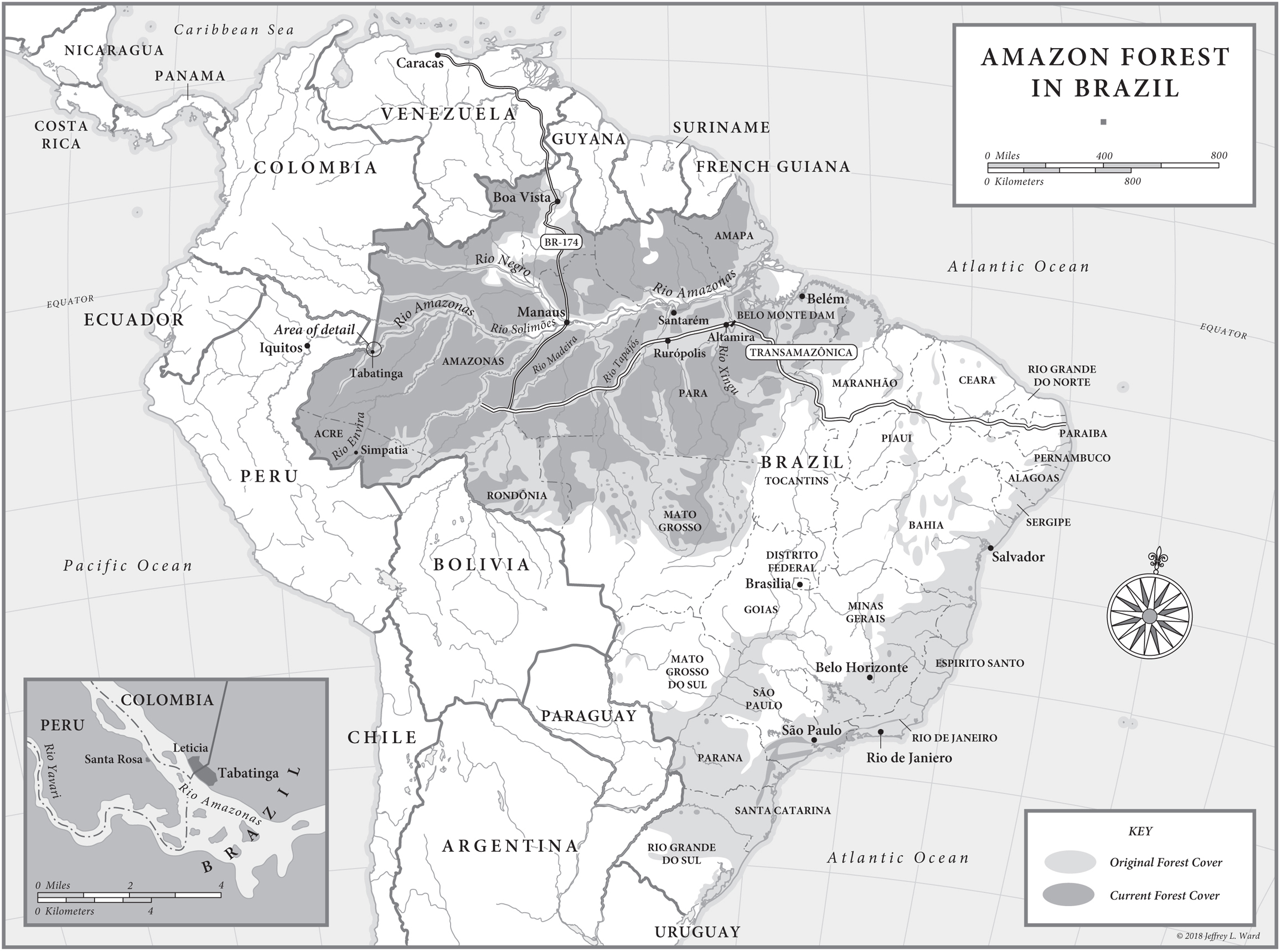

At first glance it seemed as if the World Cup in Manaus was already fulfilling its economic promise, against all odds and the will of the chiefs at FIFA, who had consulted their maps and spreadsheets and determined that the capital of Amazonas state was no place for the Cup of Cups. They said that Brazil could feasibly host matches in eight stadiums. Ten at most. Brazils national organizing committee disagreed, proposing an audacious seventeen-stadium network that would span every region of the fifth largest country on Earth. Even on paper, hosting matches in the remote interior looked like a disaster. Coastal Belm was the ideal rain forest host city. A no-brainer, as the Americans would say. Positioned at the mouth of the mighty Amazon River, Belm would fit seamlessly in the itineraries of athletes, tourists, and journalists, a quick flight from the beachfront cities of Fortaleza, Recife, and Salvador. Manaus was, well, Manaus. Aside from BR-174the cratered route to Caracas, Venezuela, that closed at sunset to accommodate nocturnal wildlife and native tribesthe city was accessible only by plane or boat. Manaus wasnt even a soccer town. Its biggest team, Nacional, hadnt competed in Brazils highest league since the waning years of the military dictatorship in the 1980s, and its neglected 12,000-seat stadium hadnt been filled to capacity for years.

Think of the athletes, those pampered, world-class specimens, flying four hours in-country to play a sweltering match in the middle of nowhere. Temperatures in Manaus hover in the nineties year-round, day and night, even during the six-month dry season. Imagine penalty kicks by players on the verge of heat stroke, goalkeepers plagued by prehistoric insects. There wouldnt even be enough bandwidth for networks to broadcast the spectacle. No, no, no. The answer was no.

But Brazils President Lula had Manaus circled on his map.

* * *

The man: Luiz Incio Lula da Silva. The myth: Lula. The legend: Born in the northeastern state of Pernambuco in the drought-stricken 1940s, Lula didnt taste bread until the age of seven, when his family climbed aboard a dusty flatbed pickup headed a thousand miles south to So Paulo, Brazils steel heart. The Silvas settled in its crowded slums. Young Lula dropped out of the sixth grade to shine shoes on the street, bankers and lawyers tossing him coins on their way to their deco high-rises. At fourteen he began working the graveyard shift in a deafening auto plant. By 1964, the year of Brazils military coup, he was nineteen years old, a veteran press machine operator at Volkswagen. During one bleary shift, as Lula reached inside a faulty press to make a repair, the operator lost control. The contraption smashed the pinky finger of Lulas left hand. He waited until his shift ended before heading to the hospital. When at last he arrived, the doctor grimaced. It was too late to save the finger. Off it went.

Decades later, Lula would tell the story on late-night talk shows, funny after all these years, shitty luck that men who wore overalls could recognize. Here was a president who understood everyday Braziliansand fought for them. During the height of the military dictatorship, when dissenters faced beatings, shock torture, or worse, Lula was a hard-drinking labor leader who stood up to the military men and the factory bosses, raising an army of workers with his gravelly voice.

In 1980, he founded the Partido dos Trabalhadores (PT)the Workers Partywhich would swell into a national political movement in the years to come, capable of paralyzing the countrys automotive industry on behalf of steelworkers. In 1987, as the military men loosened their grip on the government, Lula rose to congress as a champion of the working class. In 1989, he ran for president in the countrys first democratic elections in decades, campaigning on a leftist platform inspired by Castros revolution in Cuba. He lost. Instead of running for reelection to congress in 1990, he toured the country to galvanize the PT, sharing beers, barbecue, and sugarcane rum with workers struggling under 2,000 percent annual inflation. According to one government economist at the time, Money was like ice melting in their pockets.

In 1994, Lula again ran for president, this time against Fernando Henrique Cardoso, the former minister of finance who tamed Brazils runaway inflation by replacing its fickle currency with the real . Pegged to the U.S. dollar, the real stabilized markets, attracted foreign investment, and helped Cardoso defeat Lula in the biggest landslide in Brazils electoral history. In 1998, Lula challenged Cardoso again, criticizing the privatization of the publicly owned telecommunications, mining, and steel industries, but he was spurned by capitalists leery of handing the country over to a self-styled revolutionary who wore Che Guevara T-shirts to rallies.