The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

This book is dedicated to Denny Levy

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge the astute suggestions and tireless dedication of my editor, Cynthia Vartan; the supportive comments from Professor Jorge Preloran of the University of California, Los Angeles, Professor Carol Bardosh of New York University, playwright A. R. Gurney, and Ross Lowell, who all reviewed the manuscript and were generous with their time. Other helpful readers were Kay Michaels, Jeremy Arnold, Jim Spione, Robert Bengston, and my students at Columbia University.

Special thanks to my research assistants Denny Levy, Leslie Holland, Carla Thompson, Rebecca Watson, and Jenny Bengston.

Introduction

T HANKSGIVING . After dinner. People are scraping off the remnants from their pie plates. I suggest to a half-dozen guests that they come with me to watch a short film. Nobody moves. They keep on talking. Finally, after the third invitation, six people reluctantly follow me into a room with a VCR. On the way, one person says, I may not stay the whole time. Another says, Im supposed to be somewhere.

I have selected Time Expired by Danny Leiner. Its the story of Bobby, who returns home after a stretch in prison for stealing money from parking meters. He is cool to his wife and receives ardent phone calls from his prison cellmate, Ruby, a transvestite. With the passion of Bette Davis fighting for her man, Ruby uses every feminine wile ever tried. Bobby lies to his wife to account for his time with Ruby, and he lies to his lover about letting some time go by before they resume their relationship. Eventually, Ruby forces a showdown, and his passion prevails.

As the story unrolls, the remarks of my guests change. People are laughing. This is much better than I thought it would be, says the one who warned me he had to leave. Why cant we see things this good on TV? asks an investment banker. The film has charm and candor. It is rooted in character truth and is funnier than the average sitcom with its quota of six to eight artificial laughs per minute. Unlike the sitcom, which is shot on one set, the short changes location. People laugh because the leading man never lets go of his working-class macho demeanor and his tough-guy New York accent. Everyone leaves with a smile.

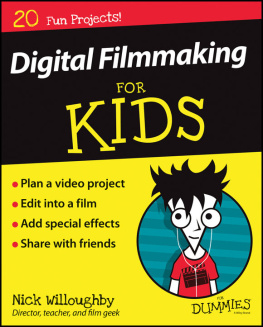

More shorts are being made today than ever before, owing to the energy and enthusiasm of film students. I have seen their talent firsthand while teaching screenwriting at Columbias School of General Studies. (My students come from Barnard, Columbia, the Graduate School of the Arts, and the working world of New York City.) Since its hard to write a feature film in a term or even two terms, I recently decided to teach the short film instead. Everyone wrote much better once the goal became writing two ten-minute scripts or one twenty-minute script in a semester. There was even time for a revision or two, which is very necessary since economy of communication can only be achieved by revision. I have now changed the curriculum so that students are first assigned to write a ten-minute almost silent script called 75 words, in which students have to communicate their ideas visually. The next assignment is to write a twenty-minute short. Students are then asked to submit three premises (the unusual conditions on which the action of the film turns), which are read and discussed in class. Finally, the class and I come to agree on which is the best premise.

When developing this curriculum, I discovered that there was no book on shorts that I could recommend to my students and that nobody had tried to explain how short-making differs from other forms of filmmaking. There were books on making expensive movies and nighttime TV shows but none that addressed the practical concerns of the student or beginning filmmaker on a limited budget. To fill this gap, I decided to write a book that would cover all facets of the short film from the writing of the screenplay to production and postproduction.

My primary objective in Making a Winning Short is to pass on my knowledge of this medium to students as well as to beginning filmmakers and videomakers. I myself never went to film school full-time. I took night courses in television at American University in Washington, D.C., while serving in the Navy. I worked in the industry and managed to stumble into situations where I had opportunities to learn. I started by writing and directing shorts. The work was very hard, and there were no books or courses to guide me. But at that time, there was a great demand for shorts on TV, in theaterswhere they were shown before the main featureand in nontheatrical settings.

This is no longer the case. The markets for shorts on TV and in theaters have dried up in the United States. But this situation is not permanent. Nor is it universal. In Europe, the former USSR, India, and other countries, the short remains an entertainment staple. My secondary goal in this book is to champion this form, to survey its riches, and perhaps to create more distribution opportunities. We are exposed to so much repetitive material that we hunger for an offbeat story like Time Expired. Yet despite the fact that many excellent shorts are available today, they have been muscled out of theaters by promotional trailers. The more the distributors are worried about the acceptability of their films, the louder and more frantic the trailer. We are the poorer for it. Shorts can communicate a wealth of experiencebeyond the marketing decisions that govern TV and most moviesand the good ones come from the heart.

Jorge Preloran, a film professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, thinks that student shorts reflect the changes in society in many ways. They deal with drug use, sexual preferences, the impact of divorce on children, new family styles and strategies, youthful unrest, the search for direction, feelings of isolation, feelings about parents, materialism, religion, new mores versus old, the loss of social guidelines, wariness about government. These shorts put a changing world under a microscope and come up with some valuable insights. If only the public could have access to them!

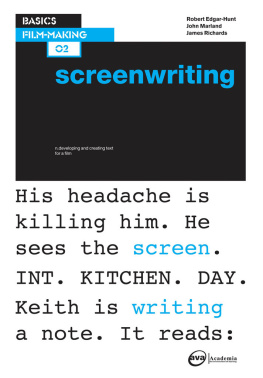

History of the Short

T HE FIRST FILMS were silent shorts. Most films before World War I lasted from one to ten minutes, and the ten-minute film, or one-reeler, was the norm. In 1902, Georges Mlis, the French pioneer, made A Trip To The Moon, a film that still provokes laughter and pleasure. It is among the hundreds of shorts he created. The following year, the American Edwin S. Porter filmed The Life of an American Fireman and The Great Train Robbery, each lasting twelve minutes. These classic films were milestones in the development of the motion picture, and the latter opened our eyes to the power of crosscutting from one story to another.

After talking pictures were introduced, the length of feature films expanded, but the short remained a staple at movie theaters. In the thirties and forties, when a ticket to the movies cost ten to fifteen cents for kids, twenty-five cents for adults, the show included a newsreel, a cartoon, a short, a cliff-hanging serial, an A picture, coming attractions, and a B picture. The movie studios had total control over production and groomed writers and directors by having them first work in the shorts and B-picture units, the film schools of their day. In the shorts unit, the studios also experimented with color and film techniques. Some shorts had stars such as Robert Benchley, Edgar Kennedy, Pete Smith, and the Three Stooges. There were even musical shorts in which audiences could watch big bands that they knew only from radio. The cheers and applause at the end of a short often would dwarf the response to a feature film. In serial shorts, audiences saw familiar characters working themselves out of a different jam every week.