W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

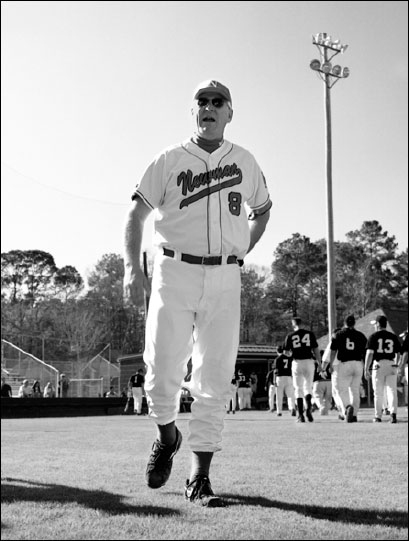

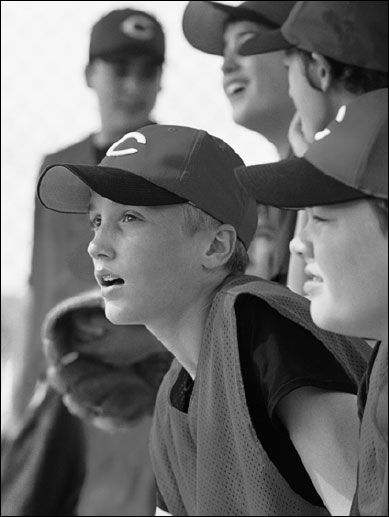

W HEN I was twelve I thought that when the New Orleans Times-Picayune ran a headline about the struggle for control of the West Bank it meant the other side of the Mississippi River. I thought that my shiny gold velour pants actually looked good. I kept a giant sack of Nabisco Chocolate Chip cookies under my bed so that they might be available in an emergencya flood, say, or a hurricanethat made it harder to get to the grocery store. From the safe distance of forty-three, twelve looks less an age than a disease, and, for the most part, Ive been able to forget all about itnot the events and the people, but the feelings that gave them meaning. But there are exceptions. A few people, and a few experiences, simply refuse to be trivialized by time. There are teachers with a rare ability to enter a childs mind; its as if their ability to get there at all gives them the right to stay forever. Id once had such a teacher. His name was Billy Fitzgerald, but everybody just called him Coach Fitz.

Forgetting Fitz was impossibleIll come to why in a momentbut avoiding him should have been a breeze. And for nearly thirty years Id had next to nothing to do with him, or with the school where hed coached me, the Isidore Newman School. But in just the past year, I heard two pieces of news about him that, taken together, made him sound suspiciously like something I never imagined he could be: a mystery. The first came last spring, when one of his former players, a forty-four-year-old New Orleans financier named David Pointer, had the idea of redoing the old schools gym, and naming it for Coach Fitz. Pointer started calling around and found that hundreds of former players and their parents shared his enthusiasm for his old coach, and the money poured in. The most common response from the parents, said Pointer, is that Fitz did all the hard work.

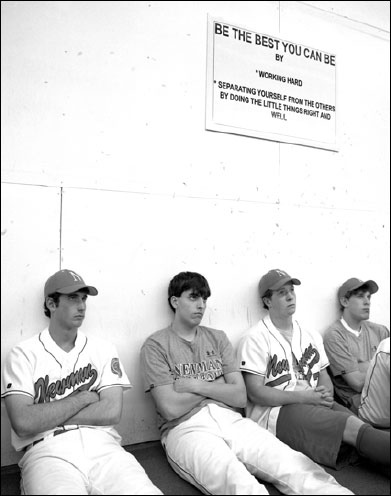

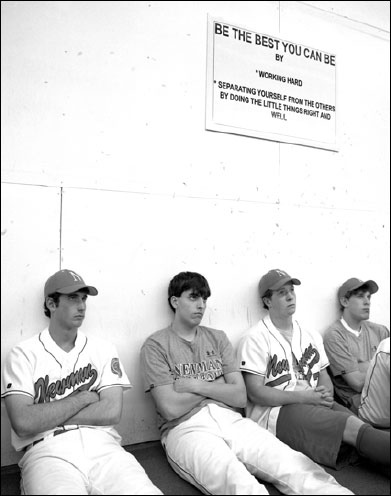

Then came the second piece of news: during the summer baseball season, Fitz had given a speech to his current Newman players. It had been a long, depressing season: the kids, who during the school year had won the Louisiana state baseball championship, had lost interest. Fitz had grown increasingly upset with them until, after their final game, hed gone around the room and explained what was wrong with each and every one of them. One player had skipped practice and lied about why; another blamed everyone but himself for his failure; a third had wasted his talent to pursue a life of ease; a fourth had agreed before the summer to lose fifteen pounds and instead gained ten. The players went home and complained about Fitz to their parents. Fathers of eight of themhalf the baseball teamhad then complained to the headmaster. Several of them wanted Fitz fired.

The past was no longer on speaking terms with the present. As the cash poured in from former players, and parents of former players, who wanted to name the gym for Fitz, his current players, and their parents, were doing their best to persuade the headmaster to get rid of him. I called a couple of the players involved, now college freshmen. Their fathers had been among the complainers, but they spoke of the episode as a kind of natural disaster beyond their control. One of them called his teammates a bunch of whiners, and explained that the reason Fitz was in such trouble was that a lot of the parents are big money donors.

I grew curious enough to fly down to New Orleans to see the headmaster. The Isidore Newman School is the sort of small, wealthy private school that every midsized American city has at least two ofone of them called Country Day. Most of the seventy or so kids in my class came from families that were affluent by local standards. Im not sure how many of us thought wed hit a triple, but quite a few had been born on third base. The schools most striking trait was that it was founded in 1903 as a manual training school for Jewish orphans. About half of my classmates were Jewish, but I didnt know any orphans. In any case, the current headmasters name was Scott McLeod, and, he said, the school hed taken charge of in 1993 was different from the school Id graduated from in 1978. The parents willingness to intercede on the kids behalf, to take the kids side, to protect the kid, in a not-healthy waytheres much more of that each year, he said. Its true in sports, its true in the classroom. And its only going to get worse. Fitz sat at the very top of the list of hardships that parents protected their kids from; indeed, the first angry call McLeod received after he became headmaster came from a father who was upset that Fitz wasnt giving his son more playing time.

Since then the beleaguered headmaster had been like a man in an earthquake straddling a fissure. On one side he had this coach about whom former players cared intensely; on the other side he had these newly organized and outraged parents of current players. When I asked him why he didnt simply ignore the parents, he said, quickly, that he couldnt do that: the parents were his customers. (They pay a hefty tuition, he said. That entitles them to a say.) But when I asked him if hed ever thought about firing Coach Fitz, he had to think hard about it. The parents want so much for their kids to have success as they define it, he said. They want them to get into the best schools, and go on to the best jobs. And so if they see their kid failif hes only on the JV, or the coach is yelling at himsomehow the school is responsible for that. And while he didnt see how he could ever fire a legend, he did see how he could change him. Several times in his tenure he had done something his predecessors never had done: summon Fitz to his office and insist that he modify his behavior. And to his credit, the headmaster said, he did that.

Obviously, whatever Fitz had done to modify his behavior hadnt satisfied his critics. But then, from where he started, he had a long way to go.