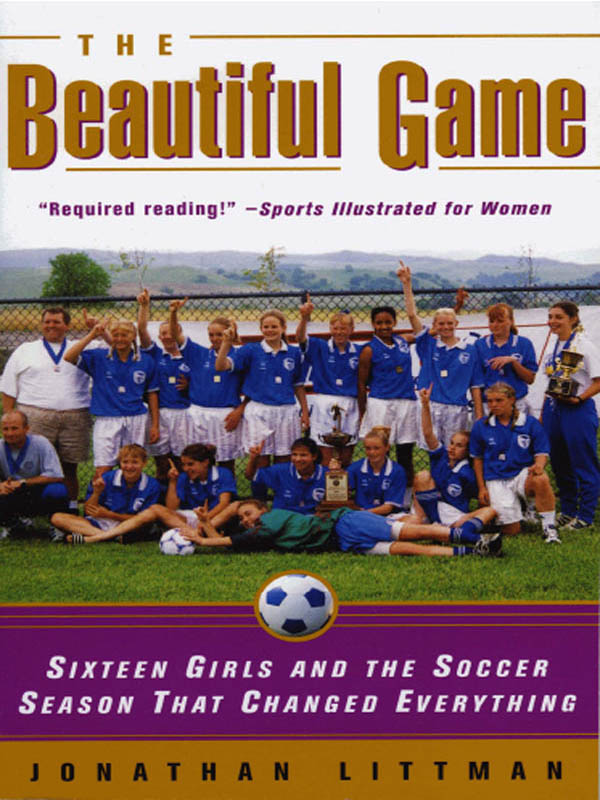

D addy, where are the girl soccer players?

There we were, sitting at what my curly-haired daughter calls the Breakfast Place, awaiting the 7:30 A.M . start of a World Cup match.

I was at a loss. Though the promise of Minnie Mouse pancakes had helped persuade my three-and-a-half-year-old that watching a soccer game on television at the town diner would be fun, there wasnt much I could do about the conspicuous absence of women players. Thankfully, my daughter is a resourceful girl. She quickly discerned that one of the French midfielders, Petit, sported a ponytail, and we spent the rest of the game anticipating the moments when his gorgeous blond locks would briefly appear on the screen. Petit, Petit! she would cry.

Over the next few weeks my daughter enjoyed the Romanian teams neon-orange-dyed hair, and countless other well-coifed players. But none of that could change the simple fact that she knew the Mens World Cup was a poor facsimile of the real thing. Shed already seen real soccer players, and she knew that they had ponytails or curls and were most definitely girls.

Months before my daughter and I trundled down to the Breakfast Place to watch the Mens World Cup, my daughter, her mother, and our eight-month-old baby girl drove north an hour to Santa Rosa on a rare dry afternoon in the midst of El Nio. We were going to watch a team of fourteen-year-old girls play soccer. I had no idea what to expect. Because the citys fields were flooded with the rains, the girls were playing indoors in the schools basketball gym. My wife and children and I sat on the creaky wooden bleachers, the lone spectators.

The girls began running laps around the gym, twenty as I recall, the slapping sound of their sneakers echoing off the walls. My eight-month-old began springing up and down like a jack-in-the-box, clapping wildly. My three-year-old couldnt take her eyes off the girls, who swept by just inches from us, fanning us in their wake. As they finished, they cheered each other on until one by one they banged open the doors to the outside, cooling off in the winter air, hoisting their jerseys to wipe the sweat off their faces.

They were strong, fast, and disciplined. They were every size and shape imaginable: tall, short, skinny, muscular. After a series of drills, they squared off in a scrimmage, and though the game was truncated by the gym, they played with grace and fierceness. Passes were crisp, and traps smooth and precise. Tackles were hard, even with the threat of the hardwood floor. I had little doubt that these girls would have trounced my eighth-grade boys team.

I had no idea if they were an average or an excellent girls team, but I couldnt think of a better place to take my two daughters on a Sunday afternoon. This was the game Id played in college and continued to love, and for me there was joy in providing my daughters this early, gripping experience of how girls master the sport. Later that evening, on the ride home, my daughter couldnt stop talking about the noisy stepping stools, and my wife and I were stumped. Stepping stools, stepping stools, what could she mean? The bleachers, of course! What an image for a three-year-old to hold in her mind. The thunderous clatter of girls sprinting up and down bleachers.

Tryouts

E lbows out and ready, the girl with the piercing eyes and apple cheeks figured she had an edge, maybe two. Jessica Marshall could play goalkeeper as well as field positions, and unlike the others, she actually knew the coach, and thus knew her elbows would count. But looking out at the sea of ponytails bobbing up and down on the vast grassy field, Jessica could also do the math. Out of the forty thirteen- and-fourteen-year-old talented girls at the tryouts, over half wouldnt last the week.

The air was crisp that April afternoon. Though a freeway bustled just a couple of hundred yards to the east, the only sound on the field was the swish of the grass underfoot, the lulling patter of the balls swinging between the players, and the symphony of breaths that rose like a tide. If this was a stadium, its walls reflected the community in which it stood. To the north loomed a destroyer-sized aluminum-sided warehouse, fronted by a fence bearing the names of local sponsors who had put up a few hundred bucks to plug their businesses: Downey Tire Center, Terchlund Law Offices, Round Table Pizza, and the local paper, the Press Democrat . Weeds choked the vast empty acreage beyond the fields, and to the west end, facing the freeway, towering eucalpytus trees promised some afternoon shade. The only amenities were a tiny blue wooden snack bar and a Porta Potti. Belluzzo Fields, they called it, the center of youth soccer in the Northern Californian city of Santa Rosa.

It was a city defined in great part by what it was not. Santa Rosa was not the prosperous and refined city of San Francisco, which lay more than fifty miles to the south. Nor was it the languorous wine country of Napa, just thirty miles to the east over the hills. Santa Rosa was an old town by western standards that was enjoying a little boom.

You could find the past in the Sonoma County Fairgrounds just a couple miles up the road from Belluzzo, where they still held Mexican dances and competitions for cows, horses, sheep, and goats. But the future was everywhere. High-tech companies had migrated north to Santa Rosa, and the town had largely shed its agricultural roots as it quickly mushroomed to nearly 150,000 people. Traffic often choked the two-lane freeway that linked Santa Rosa with the San Francisco Bay area to the south and Oregon to the north. Many parents zigzagged home from practice on side streets, fed up with the congestion. Developments were springing up all over. New homes were crowding the once rural Highway 12, which ran east to Sonoma and Napa, or west to the bucolic old town of Sebastopol, famous for its apples.