Read everything that is good for the good of your soul. Then learn to read as a writer, to search out that hidden machinery, which it is the business of art to conceal and the business of the apprentice to comprehend.

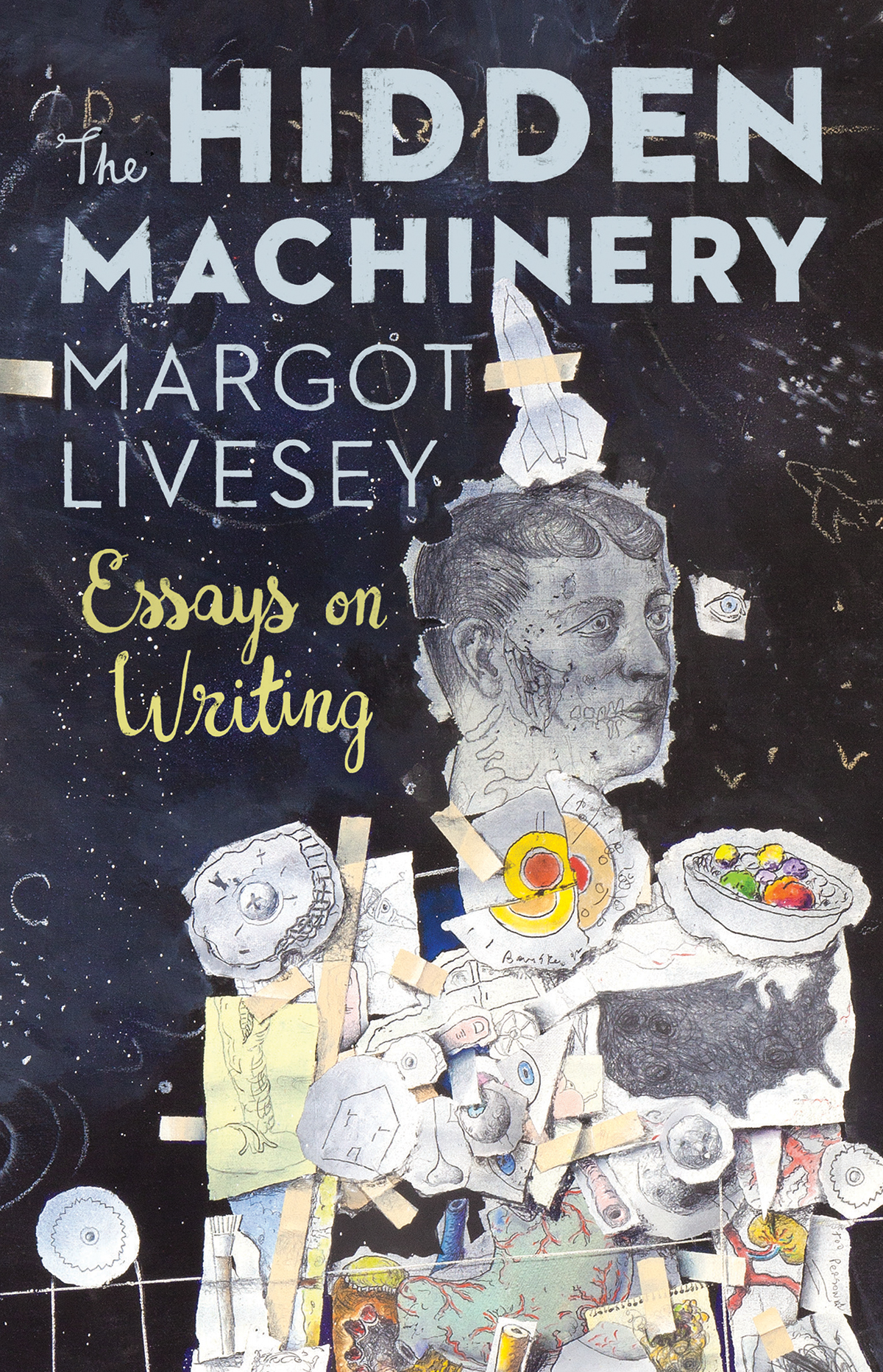

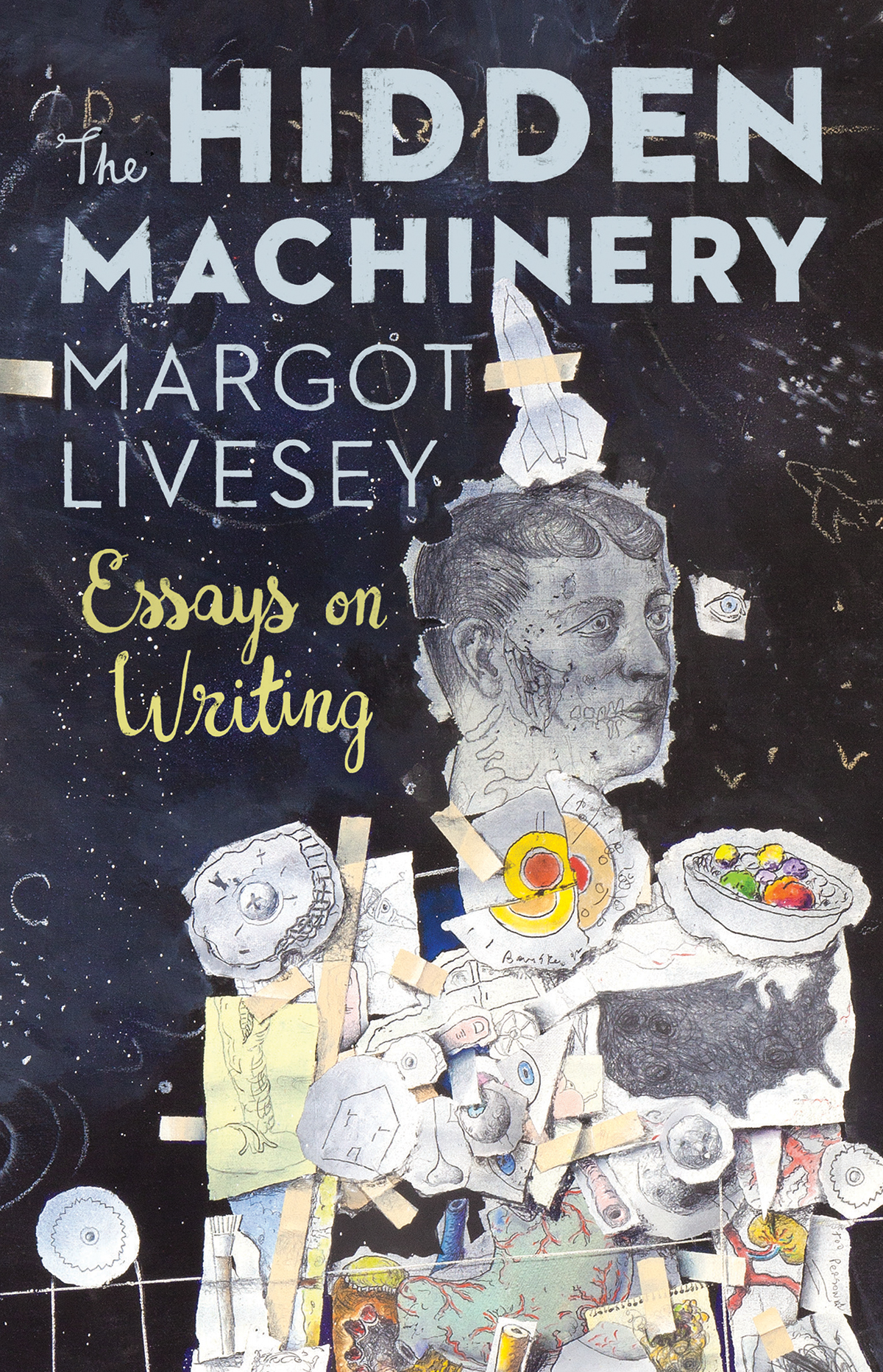

In The Hidden Machinery, critically acclaimed and New York Times best-selling author Margot Livesey offers a masterclass for those who love reading literature and for those who aspire to write it. Through close readings, arguments about craft, and personal essay, Livesey delves into the inner workings of fiction and considers how our stories and novels benefit from paying close attention both to great works of literature and to our own individual experiences. Her essays range in subject matter from navigating the shoals of research to creating characters that walk off the page, from how Flaubert came to write his first novel to how Jane Austen subverted romance in her last one. As much at home on your nightstand as it is in the classroom The Hidden Machinery will become a book readers and writers return to over and over again.

PHOTO TONY RINALDI

MARGOT LIVESEY is the author of the novels Mercury, The Flight of Gemma Hardy, The House on Fortune Street, Banishing Verona, Eva Moves the Furniture, The Missing World, Criminals, and Homework and the story collection Learning by Heart. Her work has appeared in the New Yorker, Vogue, and the Atlantic, and she is the recipient of grants from both the National Endowment for the Arts and the Guggenheim Foundation. Born in Scotland, Livesey currently lives in the Boston area and is a professor of fiction at the Iowa Writers Workshop.

Copyright 2017 Margot Livesey

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information, contact Tin House Books, 2617 NW Thurman St., Portland, OR 97210.

Published by Tin House Books, Portland, Oregon, and Brooklyn, New York

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Livesey, Margot.

Title: The hidden machinery / by Margot Livesey.

Description: First U.S. edition. | Portland, OR :

Tin House Books, 2017.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016056392 | ISBN 9781941040683

(alk. paper) | ISBN 978-1-941040-69-0 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: FictionAuthorship. | Creative writing. |

Livesey, MargotAuthorship.

Classification: LCC PN3355 .L557 2017 | DDC 808.3dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016056392

First US Edition 2017

Interior design by Jakob Vala

www.tinhouse.com

Life is Monstrous, infinite, illogical, abrupt and poignant; a work of art, in comparison, is neat, finite, self-contained, rational, flowing and e masculate... To compete with life, whose sun we cannot look upon, whose passions and diseases waste and slay us, to compete with the flavor of wine, the beauty of the dawn, the scorching of fire, the bitterness of death and s eparation... here are indeed labours for a Hercules in a dress coat, armed with a pen and a dictionary... No art is true in this sense; none can compete with life...

ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON ,

A Humble Remonstrance

I

ON THE BOOKSHELVES of my house in London are the books I read as a child: Robert Louis Stevensons Kidnapped, Kenneth Grahames The Wind in the Willows, Lewis Carrolls Alices Adventures in Wonderland, George MacDonalds The Princess and Curdie, and a strange book called The Pheasant Shoots Back by Dacre Balsdon. This last, a kind of Animal Farm for birds, describes how a family of pheasants outwits the hunters and lives to fly another season. My great-aunt Jean thought it a suitable gift for my fifth birthday. Certainly I appreciated the sky-blue cover and the simple line drawings, but the black marks that covered the pages were a mystery, and not one I was eager to solve. Reading struck me as much less important than tree climbing or bridge building or visiting the nearby pigs. Sometime that autumn, however, my priorities shifted. I remember standing in the corner of the nursery, where we had our lessons, refusing to read, when, quite suddenly, the words turned from a walllike the one I was staring atinto a window. I was looking through them at a farmyard filled with animals. I emerged from the corner and read Percy the Bad Chick. Here was someone like myselfsmall, naughty, friendlessyet look how Percy triumphed over the other animals, including Dobbin, the farmers horse. From then on I embraced books. I had, although the word remained unknown to me for several years, discovered novels.

Who do you want to be when you grow up? the grown-ups around me asked.

Not you, I wanted to say, but I was a well-brought-up child. A nun, I responded, a vet, an explorer, Marie Curie. Each profession came from a book I had read. I was slow to grasp that the person I wanted to be was not someone between the covers but behind them. By the time I went to university I had relinquished my ambition to discover a new element and was studying literature and philosophy, mostly the former. Our curriculum began with Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and Chaucer and zigzagged erratically forward until we reached Virginia Woolf, still at that time a relatively minor figure. Then we came to an abrupt halt. One faculty member was rumored to be doing research into a living author, the Australian novelist Patrick White, but that was a private activity; he lectured on the safely interred: Eliot, Pound, and Joyce. Nonetheless news reached me from the larger world that there were authorsSaul Bellow, Margaret Drabble, Doris Lessing, Solzhenitsynliving, breathing, making novels out of the fabric of contemporary life. Among my fellow students one or two claimed to be writing poetry, but the evidence was scanty.

The year after I graduated from university I went traveling in Europe and North Africa with my boyfriend of the time. He was writing a book on the philosophy of science and after a few weeks, bored with exploring cathedrals and markets alone, I began to write a book too. I did not know enough to write a history of the Crusades, or a biography of the Bronts, but, after sixteen years of reading, I felt amply qualified to write a novel. After all, this was the only training that most of my favorite writers had undergone. Read good authors with passionate attention, runs Robert Louis Stevensons advice to a young writer, refrain altogether from reading bad ones.

I began writing The Oubliette in October. (The title refers, with unwitting irony, to the French dungeon in which prisoners were kept until they were forgotten.) In campsites and cheap hotels I did my best to imitate Trollope, writing for so many hours a day. l wrote in pencil, rubbing out frequently, on every other line of a spiral notebook. I filled one notebook, began another, and filled that too. My novel was growing. By the following June I had a draft: four hundred pages of made-up people, doing made-up things. While I wrote, I was doing my best to follow Stevensons advice. I read Richard Brautigan and Elizabeth Bowen, Malcolm Lowry and Edna OBrien, Henry James and Ralph Ellison,

Next page