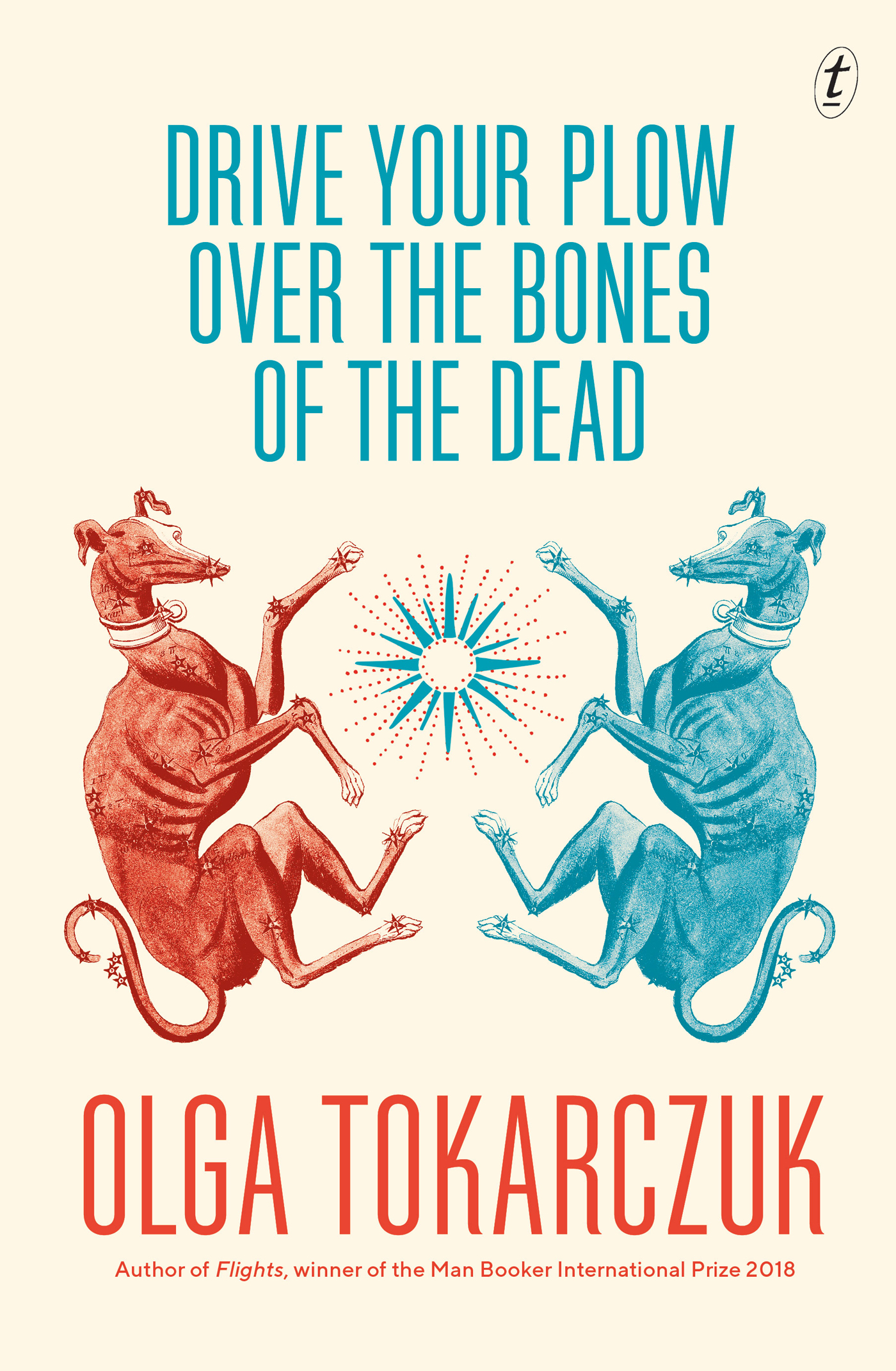

Drive Your Plow

DUSZEJKO IS IN HER SIXTIES, AN ECCENTRIC schoolteacher and caretaker of holiday homes who lives in a remote Polish village. Her two beloved dogs disappear, and then members of a local hunting club are found murdered; she decides to get involved in the investigation. But she has her own theories about things because she reads the stars, as well as the poetry of William Blake.

Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead is an entertaining thriller by the author of Flights, winner of the Man Booker International Prize. In this scintillating translation by Antonia Lloyd-Jones, Olga Tokarczuk explores ideas about madness, injustice, animal rights, hypocrisy and predestination-and how to get away with murder.

A strongly voiced existential thriller. Guardian

Tokarczuk is one of Europes most daring and original writers. Los Angeles Review of Books

Once meek, and in a perilous path,

The just man kept his course along

The vale of death.

I am already at an age and additionally in a state where I must always wash my feet thoroughly before bed, in the event of having to be removed by an ambulance in the Night.

Had I examined the Ephemerides that evening to see what was happening in the sky, I wouldnt have gone to bed at all. Meanwhile I had fallen very fast asleep; I had helped myself with an infusion of hops, and I also took two valerian pills. So when I was woken in the middle of the Night by hammering on the door violent, immoderate and thus ill-omened I was unable to come round. I sprang up and stood by the bed, unsteadily, because my sleepy, shaky body couldnt make the leap from the innocence of sleep into wakefulness. I felt weak and began to reel, as if about to lose consciousness. Unfortunately this has been happening to me lately, and has to do with my Ailments. I had to sit down and tell myself several times: Im at home, its Night, someones banging on the door. Only then did I manage to control my nerves. As I searched for my slippers in the dark, I could hear that whoever had been banging was now walking around the house, muttering. Downstairs, in the cubbyhole for the electrical meters, I keep the pepper spray Dizzy gave me because of the poachers, and that was what now came to mind. In the darkness I managed to seek out the familiar, cold aerosol shape, and thus armed, I switched on the outside light, then looked at the porch through a small side window. There was a crunch of snow, and into my field of vision came my neighbour, whom I call Oddball. He was wrapping himself in the tails of the old sheepskin coat Id sometimes seen him wearing as he worked outside the house. Below the coat I could see his striped pyjamas and heavy hiking boots.

Open up, he said.

With undisguised astonishment he cast a glance at my linen suit (I sleep in something the Professor and his wife wanted to throw away last summer, which reminds me of a fashion from the past and the days of my youth thus I combine the Practical and the Sentimental) and without a by-your-leave he came inside.

Please get dressed. Big Foot is dead.

For a while I was speechless with shock; without a word I put on my tall snow boots and the first fleece to hand from the coat rack. Outside, in the pool of light falling from the porch lamp, the snow was changing into a slow, sleepy shower. Oddball stood next to me in silence, tall, thin and bony like a figure sketched in a few pencil strokes. Every time he moved, snow fell from him like icing sugar from pastry ribbons.

What do you mean, dead? I finally asked, my throat tightening, as I opened the door, but Oddball didnt answer.

He generally doesnt say much. He must have Mercury in a reticent sign, I reckon its in Capricorn or on the cusp, in square or maybe in opposition to Saturn. It could also be Mercury in retrograde that produces reserve.

We left the house and were instantly engulfed by the familiar cold, wet air that reminds us every winter that the world was not created for Mankind, and for at least half the year it shows us how very hostile it is to us. The frost brutally assailed our cheeks, and clouds of white steam came streaming from our mouths. The porch light went out automatically and we walked across the crunching snow in total darkness, except for Oddballs headlamp, which pierced the pitch dark in one shifting spot, just in front of him, as I tripped along in the Murk behind him.

Dont you have a torch? he asked.

Of course I had one, but I wouldnt be able to tell where it was until morning, in the daylight. Its a feature of torches that theyre only visible in the daytime.

Big Foots cottage stood slightly out of the way, higher up than the other houses. It was one of three inhabited all year round. Only he, Oddball and I lived here without fear of the winter; all the other inhabitants had sealed their houses shut in October, drained the water from the pipes and gone back to the city.

Now we turned off the partly cleared road that runs across our hamlet and splits into paths leading to each of the houses. A path trodden in deep snow led to Big Foots house, so narrow that you had to set one foot behind the other while trying to keep your balance.

It wont be a pretty sight, warned Oddball, turning to face me, and briefly blinding me with his headlamp.

I wasnt expecting anything else. For a while he was silent, and then, as if to explain himself, he said: I was alarmed by the light in his kitchen and the dog barking so plaintively. Didnt you hear it?

No, I didnt. I was asleep, numbed by hops and valerian.

Where is she now, the Dog?

I took her away from here shes at my place. I fed her and she seemed to calm down.

Another moment of silence.

He always put out the light and went to bed early to save money, but this time it continued to burn. A bright streak against the snow. Visible from my bedroom window. So I went over there, thinking he might have got drunk or was doing the dog harm, for it to be howling like that.

We passed a tumbledown barn and moments later Oddballs torch fetched out of the darkness two pairs of shining eyes, pale green and fluorescent.

Look, Deer, I said in a raised whisper, grabbing him by the coat sleeve. Theyve come so close to the house. Arent they afraid?

The Deer were standing in the snow almost up to their bellies. They gazed at us calmly, as if we had caught them in the middle of performing a ritual whose meaning we couldnt fathom. It was dark, so I couldnt tell if they were the same Young Ladies who had come here from the Czech Republic in the autumn, or some new ones. And in fact why only two? That time there had been at least four of them.

Go home, I said to the Deer, and started waving my arms. They twitched, but didnt move. They calmly stared after us, all the way to the front door. A shiver ran through me.

Meanwhile Oddball was stamping his feet to shake the snow off his boots outside the neglected cottage. The small windows were sealed with plastic and cardboard, and the wooden door was covered with black tar paper.

The walls in the hall were stacked with firewood for the stove, logs of uneven size. The interior was nasty, dirty and neglected. Throughout there was a smell of damp, of wood and earth moist and voracious. The stink of smoke, years old, had settled on the walls in a greasy layer.

The door into the kitchen was ajar, and at once I saw Big Foots body lying on the floor. Almost as soon as my gaze landed on him, it leaped away. It was a while before I could look over there again. It was a dreadful sight.

Next page

![Dzhejms CHejz - Safer Dead [= Dead Ringer]](/uploads/posts/book/910100/thumbs/dzhejms-chejz-safer-dead-dead-ringer.jpg)