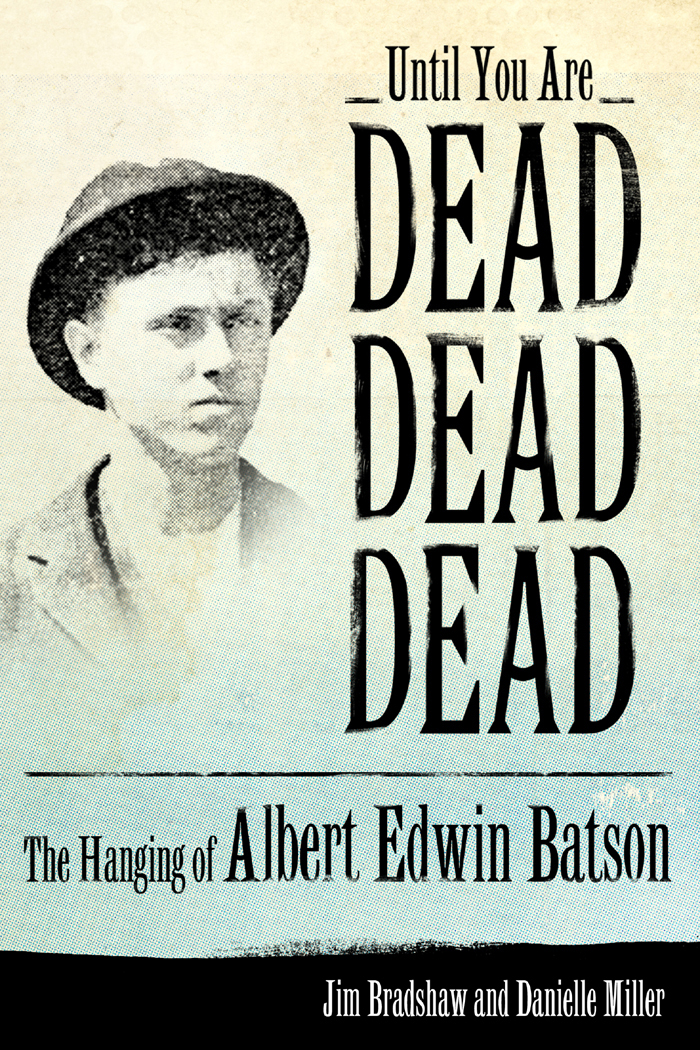

Afterword

Beyond Reasonable Doubt?

In the United States our system of laws holds that a person accused of wrongdoing is presumed innocent until proven guilty. Many think that principle is part of the U.S. Constitution, but in fact, it predates the Constitution, coming to American jurisprudence from English Common Law.

Not only must a defendant be proven guilty, it must be beyond reasonable doubt; that is, a juror must have a real reason to find a defendant guilty or innocent of a crime. To meet the legal criterion, any doubt of guilt must be based upon reason and common sense after careful consideration of all the evidence, or lack of evidence, in a case.

Proof beyond a reasonable doubt does not mean absolute certainty, but it does mean the presence of enough certainty that a reasonable person would be willing to accept it and act upon it. A majority of the people of southwest Louisiana believed that the case against Batson met that criterion; some others thought his guilt had not been fully proven, or at least not fully enough to warrant the death penalty.

On the day of his death, the New Orleans Picayune reported,

The story of the murder, the events which led to the accusation against Batson, his flight and arrest in Spickard, Mo., the day after the murder was unearthed ... his manner, actions and professions of innocence, his lack of a defense, his trial and conviction, his appeal for a new trial and the granting of the same by the Supreme Court, and his second trial and conviction reads like a romance. But few people residing in Lake Charles had any doubt of his guilt.... A number of people however, doubted that Batson was the guilty party. Some did not think that the guilt had been proven beyond a doubt, and hinged their belief upon his protestations of innocence and the language of the man, and the coolness that he displayed at all times during his two trials, in prison and while conversing with others. Careful guard was set upon him, he was watched day and night, yet not once did he betray either by word or deed any knowledge of the crime.

But there was yet another reason urged by those who would not believe Batson guilty of the crime, and that was the absence of any motive for such a horrible deed.... [The stealing of the stock] could not have been his motive. First, there was much more stock on the rice farms than was found in Batsons possession ... [which] did not form a third of the stock on the place, and [there] was a question of what became of the rest of the stock.... It had never been claimed by the State that Batson was searching for money, as it was known to him that Ward Earll invariably deposited his money in the bank in Welsh.

In his charge to the jury, Judge Miller explained that a reasonable doubt is when a specific reason can be found, and that if jurors had such a doubt, it was their duty to acquit Ed Batson. Defense attorneys emphasized that circumstantial evidence is competent evidence under the law, but every circumstance must fit the picture, and, further, it must be found that there are no reasonable circumstances under which someone else could have committed the crime.

Putting ourselves in the place of a juror at that time and place before the introduction of modern crime-solving methods such as DNA testing, would we have found there was sufficient evidence for Albert Edwin Batson to have been hanged? Or would we have had a reasonable doubt?

There is no way to know a century later whether this young stranger from Missouri was guilty or innocent of the Earll murders. We believe, however, that even from this distance of years, a reasonable person can certainly think Ed Batson should not have been hanged, and his sentence should have been no more than life in prison, as the pardon board recommended.

Indeed, it is interesting to speculate whether that might have been the outcome at trial had a decision such as in the case of Witherspoon v. Illinois in 1968 been made before 1903. In that case the U.S. Supreme Court held that the death penalty can be invalid if people who object to the death penalty are systematically excluded from the jury.

As in the Batson case, the jury in Witherspoon had the option of deciding guilt with or without capital punishment and, if reports are true, two Batson jurors preferred to recommend life in prison over death. Would a modern jury agree with them? The court said in Witherspoon that questions of guilt and questions of punishment are separate, and it is possible that a jury can show no bias in deciding guilt but hold substantial bias in deciding the proper sentence.

In the Witherspoon decision, the majority held:

In this case the jury was entrusted with two distinct responsibilities: first, to determine whether the petitioner was innocent or guilty; and second, if guilty, to determine whether his sentence should be imprisonment or death. It has not been shown that this jury was biased with respect to the petitioners guilt. But it is self-evident that, in its role as arbiter of the punishment to be imposed, this jury fell woefully short of that impartiality to which the petitioner was entitled.... Whatever else might be said of capital punishment, it is at least clear that its imposition by a hanging jury cannot be squared with the Constitution.

The juries in both Batson trials were carefully selected on the basis of their belief in capital punishment based on circumstantial evidence. They probably did not meet Witherspoon standards. But even under the rules in play at the time of Batsons trials, significant issues arise.

First, questions remain about when the crime was committed and how that fits with claims by Batson and by his accusers of where he was at the time of the murders. The coroner, Dr. Watkins, testified that decomposition of the bodies made it impossible to say exactly when the Earlls were murdered, and that from the physical evidence he could only estimate the time of death within a five- to twelve-day period. The time of the murder was set as February 13 because Ward Earll had been seen in Welsh on February 12, and because the man with the scar and the mules was seen in the Louisiana town of Iowa on the evening of February 13. But there is no substantial link between either event and the murders, and Ed Batson maintained he was already riding the rails toward Texas on February 13.

Second, when were the different victims killed? It was apparently assumed in all the written material about the murder of the Earll family, and during the Batson trials, that the mother and children were killed before L .S. Earll, based simply on the fact that their bodies were found first.

But if the motive for the murders was money, it is much more likely that L. S. Earll had more of it than his son Ward. The father had the bigger farm, had sold the bigger rice crop, and was probably more conservative with his money than Ward, who was described by some people who knew him as a gambler, drinker, and wastrel. If that was the case, a would-be robber would go to the father first, and he would have been the first one killed. Consider the following scenario as a possibility:

Ward is ill after having stayed too long at the Mardi Gras festivities, and his mother goes to his house to take care of him. The younger boys are at school, which leaves L. S. Earll alone at home. Either by chance or design, someone finds the older man alone and tries to rob him. Earll resists and is shot, then his house is searched for money. Note that L. S. Earlls body was found partially buried, meaning that the killer had taken time to try to dispose of it, which was not the case with the rest of his family.