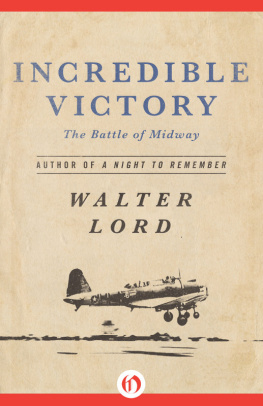

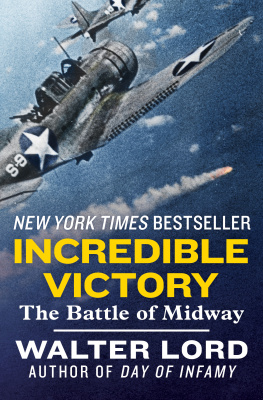

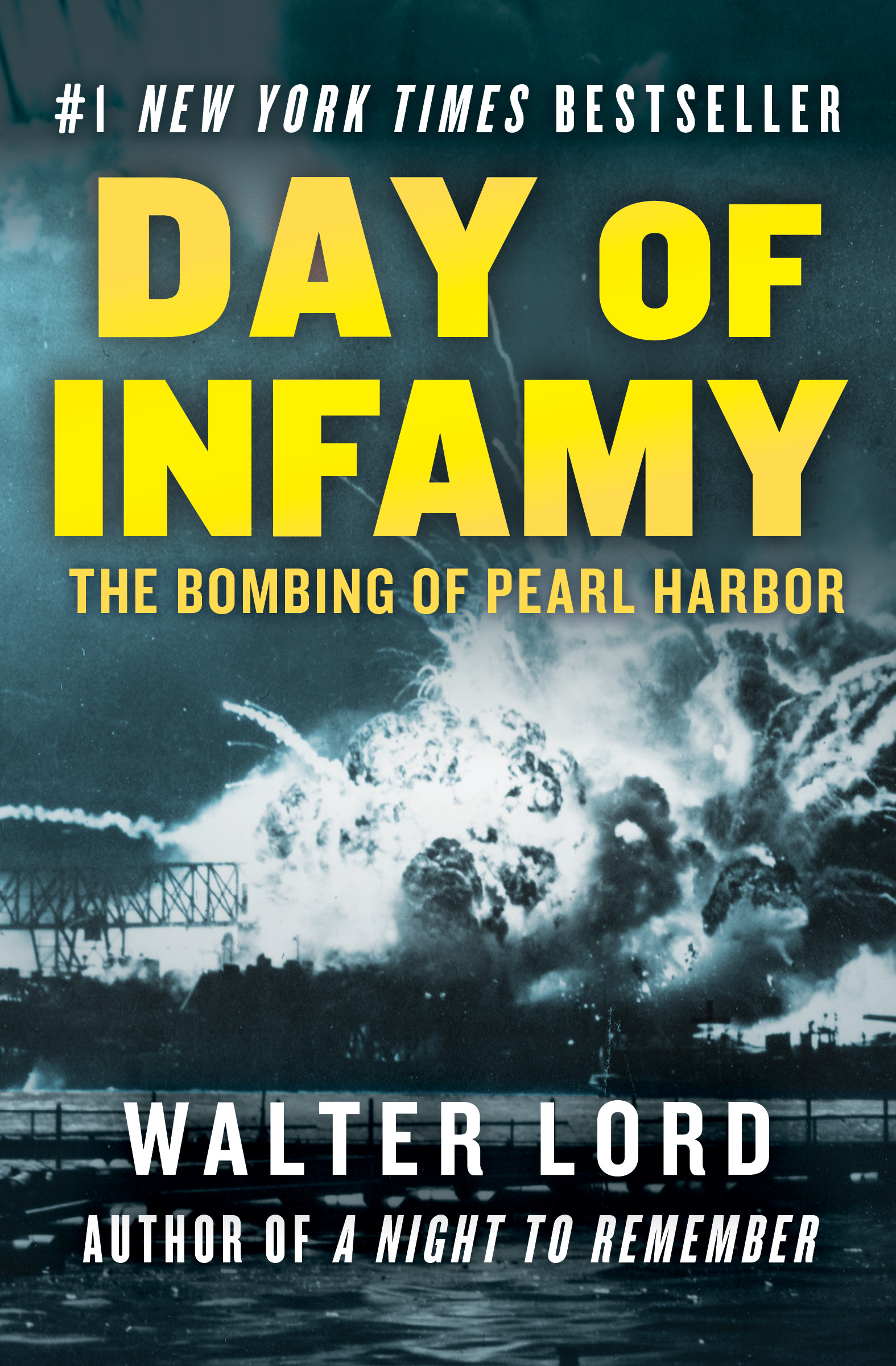

Day of Infamy

Walter Lord

To Lanet Cody

FOREWORD

IT HAPPENED ON DECEMBER 7, 1941.

One part of America learned while listening to the broadcast of the Dodger-Giant football game at the Polo Grounds in New York. Ward Cuff had just returned a Brooklyn kickoff to the 27-yard line when at 2:26 P.M. WOR interrupted with the first flash: the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor.

Another part of America learned half an hour later, while tuning in the New York Philharmonic concert at Carnegie Hall. Artur Rodzinskis musicians were just about to start Shostakovichs Symphony Number 1 when CBS repeated an earlier bulletin announcing the attack.

The concertgoers themselves learned still later when announcer Warren Sweeney told them at the end of the performance. Then he called for The Star-Spangled Banner. The anthem had already been played at the start of the concert, but the audience had merely hummed along. Now they sang the words.

Others learned in other ways, but no matter how they learned, it was a day they would never forget. Nearly every American alive at the time can describe how he first heard the news. He marked the moment carefully, carving out a sort of mental souvenir, for instinctively he knew how much his life would be changed by what was happening in Hawaii.

This is the story of that day.

CHAPTER I

Isnt That a Beautiful Sight?

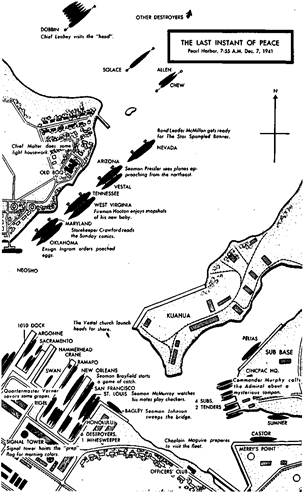

MONICA CONTER, A YOUNG Army nurse, and Second Lieutenant Barney Benning of the Coast Artillery strolled out of the Pearl Harbor Officers Club, down the path near the ironwood trees, and stood by the club landing, watching the launches take men back to the warships riding at anchor.

They were engaged, and the setting was perfect. The workshops, the big hammerhead crane, all the paraphernalia of the Navys great Hawaiian base were hidden by the night; the daytime clatter was gone; only the pretty things were left the moonlight the dance music that drifted from the club the lights of the Pacific Fleet that shimmered across the harbor.

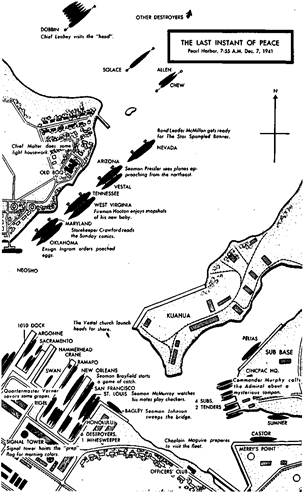

And there were more lights than ever before. For the first weekend since July 4 all the battleships were in port at once. Normally they took turns six might be out with Admiral Pyes battleship task force, or three would be off with Admiral Halseys carrier task force. This was Pyes turn in, but Halsey was out on a special assignment that meant leaving his battleships behind. A secret war warning had been received from Washington Japan was expected to hit the Philippines, Thai, or Kra Peninsula or possibly Borneo and the carrier Enterprise was ferrying a squadron of Marine fighters to reinforce Wake Island. Battleships would slow the task forces speed from 30 to 17 knots. Yet they were too vulnerable to maneuver alone without carrier protection. The only other carrier, the Lexington, was off ferrying planes to Midway, so the battleships stayed at Pearl Harbor, where it was safe.

With the big ships in port, the officers club seemed even gayer and more crowded than usual, as Monica Conter and Lieutenant Benning walked back and rejoined the group at the table. Somebody suggested calling Lieutenant Bill Silvester, a friend of them all who this particular evening was dining eight miles away in downtown Honolulu. Monica called him, playfully scolded him for deserting his buddies the kind of call that has been placed thousands of times by young people late in the evening, and memorable this time only because it was the last night Bill Silvester would be alive.

Then back to the dance, which was really a conglomeration of Dutch treats and small private parties given by various officers for their friends: Captain Montgomery E. Higgins and Mrs. Higgins entertained at the Pearl Harbor Officers Club Lieutenant Commander and Mrs. Harold Pullen gave a dinner at the Pearl Harbor Officers Club the Honolulu Sunday Advertiser rattled them off in its society column the following morning.

Gay but hardly giddy. The bar always closed at midnight. The band seemed in a bit of a rut its favorite Sweet Leilani was now over four years old. The place itself was the standard blend of chrome, plywood, and synthetic leather, typical of all officers clubs everywhere. But it was cheap dinner for a dollar and it was friendly. In the Navy everybody still seemed to know everybody else on December 6, 1941.

Twelve miles away, Brigadier General Durward S. Wilson, commanding the 24th Infantry Division, was enjoying the same kind of evening at the Schofield Barracks Officers Club. Here, too, the weekly Saturday night dance seemed even gayer than usual partly because many of the troops in the 24th and 25th Divisions had just come off a long, tough week in the field; partly because it was the night of Ann Etzlers Cabaret, a benefit show worked up annually by one of the very talented young ladies on the post, as General Wilson gallantly puts it. The show featured amateur singing and dancing a little corny perhaps, but it was all in the name of charity and enjoyed the support of everybody who counted, including Lieut. General Walter C. Short, commanding general of the Hawaiian Department.

Actually, General Short was late. He had been trapped by a phone call, just as he and his intelligence officer, Lieutenant Colonel Kendall Fielder, were leaving for the party from their quarters at Fort Shafter, the Armys administrative headquarters just outside Honolulu. Lieutenant Colonel George Bicknell, Shorts counterintelligence officer, was on the wire. He asked them to wait; he had something interesting to show them. The general said all right, but hurry.

At 6:30 Bicknell puffed up. Then, while Mrs. Short and Mrs. Fielder fretted and fumed in the car, the three men sat down together on the commanding generals lanai. Colonel Bicknell produced the transcript of a phone conversation monitored the day before by the local FBI. It was a call placed by someone on the Tokyo newspaper Yomiuri Shinbun to Dr. Motokazu Mori, a local Japanese dentist and husband of the papers Honolulu correspondent.

Tokyo asked about conditions in general: about planes, searchlights, the weather, the number of sailors around and about flowers. Presently, offered Dr. Mori, the flowers in bloom are fewest out of the whole year. However, the hibiscus and the poinsettia are in bloom now.

The three officers hashed it over. Why would anyone spend the cost of a transpacific phone call discussing flowers? But if this was code, why talk in the clear about things like planes and searchlights? And would a spy use the telephone? On the other hand, what else could be going on? Was there any connection with the cable recently received from Washington warning hostile action possible at any moment?

Fifteen minutes half an hour nearly an hour skipped by, and they couldnt make up their minds. Finally General Short gently suggested that Colonel Bicknell was too intelligence-conscious; in any case they couldnt do anything about it tonight; they would think it over some more and talk about it in the morning.

Next page