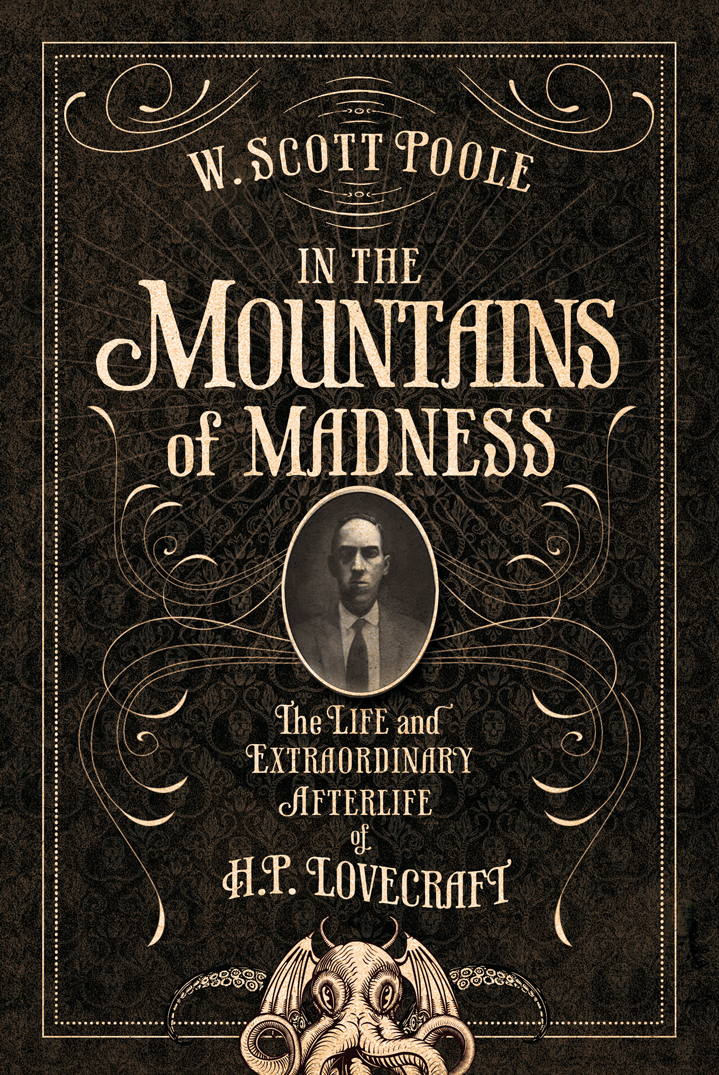

Copyright 2016 by W. Scott Poole

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Cover design by Charles Brock, Faceout Studio

Interior design by Tabitha Lahr

SOFT SKULL PRESS

An imprint of Counterpoint

2560 Ninth Street, Suite 318

Berkeley, CA 94710

www.softskull.com

Distributed by Publishers Group West

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

ebook ISBN 9781619028562

For Em

One need not be a Chamberto be Haunted

One need not be a House

The Brain has Corridorssurpassing

Material Place

Far safer, of a Midnight Meeting

External Ghost

Than its interior Confronting

That Cooler Host.

Far safer, through an Abbey gallop,

The Stones achase

Than Unarmed, ones aself encounter

In lonesome Place

EMILY DICKINSON

... the motor chewed up a whole roll of film as the flash angrily slashes out at the prevailing darkness, ultimately capturing this dark form, vanishing behind a closing door...

MARK Z. DANIELEWSKI, HOUSE OF LEAVES

Table of Contents

Guide

CONTENTS

I think I went mad then.

H oward Phillips Lovecraft wrote these words at his window desk in the quickly fading heat of the summer of 1917.

The smooth roll of fountain pen on paper mingled with provoking street noise entering the window at 598 Angell Street in Providence, Rhode Island. The slender twenty-six-year-old found these human sounds excessively bothersome. A decline in family fortune forever separated him from the quiet Victorian dignity that money could buy. He sometimes fantasized about becoming deaf and retreating forever into his interior worlds, realms of darkly intoxicating beauty and horror.

He owned a 1906 Remington typewriter but seldom used it. Nightfall signaled the beginning of his writing workday. He convinced himself that the sound of a typewriter would disturb his neighbors as much as it disturbed him. He came to so dislike its industrial clatter that he sometimes declined to publish his tales rather than prepare a typescript of them.

Many Lovecraft stories would never have appeared in any form if some of his acolytes not taken the trouble to pound them out for him on their own typewriters. This came to constitute a major theme in the Lovecraft phenomenon. Adoring admirers taking an obsessional interest in his work kept him from disappearing into pulp oblivion forever, a prospect he seemed in some bizarre fashion to desire.

I do not think his current fame would have pleased him. He would have hated the flood of books about him and their speculations or assertions about his personal life. He would have hated the book you hold in your hands and what it tells about the inner worlds of a gentleman from Providence who consistently lied to the world about who and what he had been, performing more radical revisions on his life story than he ever bothered to make in the fiction that has made him famous.

But in 1917, he lived in almost complete obscurity, an obscurity he couldnt escape even when he tried. America had entered the First World War in April of that year and, to the surprise of everyone that knew him, Lovecraft, who turned twenty-seven that summer, volunteered for service. The army almost immediately rejected him, largely because his mother, Sarah Susan Lovecraft, made use of family connections to have him declared medically unfit.

Lovecraft described himself, at various times in his life, as having a weak heart, neuralgic, a sufferer of night terrors, a para-insomniac, and, more generally, the victim of a nervous disposition. None of his alleged ailments kept him from what likely would have amounted to limited stateside military service. In a letter to his fellow amateur journalist Reinhardt Kleiner, Lovecraft described his mother as prostrated with the news that he had hoped to join the war effort. He sheepishly admitted that she had threatened to go to any lengths, legal or otherwise, if I do not reveal all the ills which unfit me for the army.

Howard Lovecraft, who walked with an old mans stoop but could also be seen vigorously cycling the decaying graveyards and dark forest paths of New England, accepted his failed attempt to join the army with his usual fatalism about human existence, a bitterness against life tinged with a peculiar sense of humor. Only those few who knew him best ever fully experienced his unlikely combination of pomposity and capacity for self-parody. Lovecraft, perhaps more than any important writer of the twentieth century, knew that the joke was on him.

In the first twenty-seven years of his life, H.P. Lovecraft had seen his father confined to a mental institution and subsequently die at an early age. At fourteen, while on one of his long bicycle rides, the young Howard contemplated drowning himself in the Barrington River. He dropped out of high school because of a mysterious and unexplained nervous condition that turned him into a virtual recluse between 1908 and 1913.

The boom in amateur journalism of the 1910s brought him out of what he called a vegetative state and gave him limited but meaningful human contact through a vast circle of correspondence that replicated certain aspects of contemporary social media. In the years to come, he would marry the unlikeliest woman in the world, move to New York City, get divorced (sort of), ghostwrite for Harry Houdini, watch Tod Brownings Dracula and not especially enjoy it (or the city where he saw it) one tropical Miami night, and write stories for the American pulps that transformed the landscape of American popular culture in ways he could not begin to imagine.

Over a twenty-year period, in fits and starts, Lovecraft created a collection of stories that made possible the work of Stephen King, Ramsey Campbell, Guillermo del Toro, and John Carpenter. He dreamed of monsters and fantastic worlds that created cultural behemoths like San Diego Comic-Con. His outr and gruesome imagery influenced heavy metal music and informed the world building of both tabletop role-playing games like Dungeons & Dragons and even direct adaptations of his own imaginative universe. His work has appeared in enormously popular modern video games like Witchfinder, The Elder Scrolls, and the Dragon Age series.

A quick search online locates hundreds of Lovecraftian T-shirts, coffee mugs, fan art, and even versions of his tales produced as earlytwentieth-century radio shows. Hipsters tattoo themselves with his monsters. A trendy Manhattan cocktail bar called Lovecrafts uses his stories for their menu while in Boones Bar in Charleston, South Carolina there hangs an image of the tentacles of Cthulhu, grasping menacingly at you as you scan their long list of upscale bourbons and scotches. The lifelong teetotaler would be astonished by this and by a New Englandbased brewing company that sells a line of craft beers using both his image and elements of his fiction.