H.P. LOVECRAFT

INTRODUCTION

Lovecrafts Pillow

by STEPHEN KING

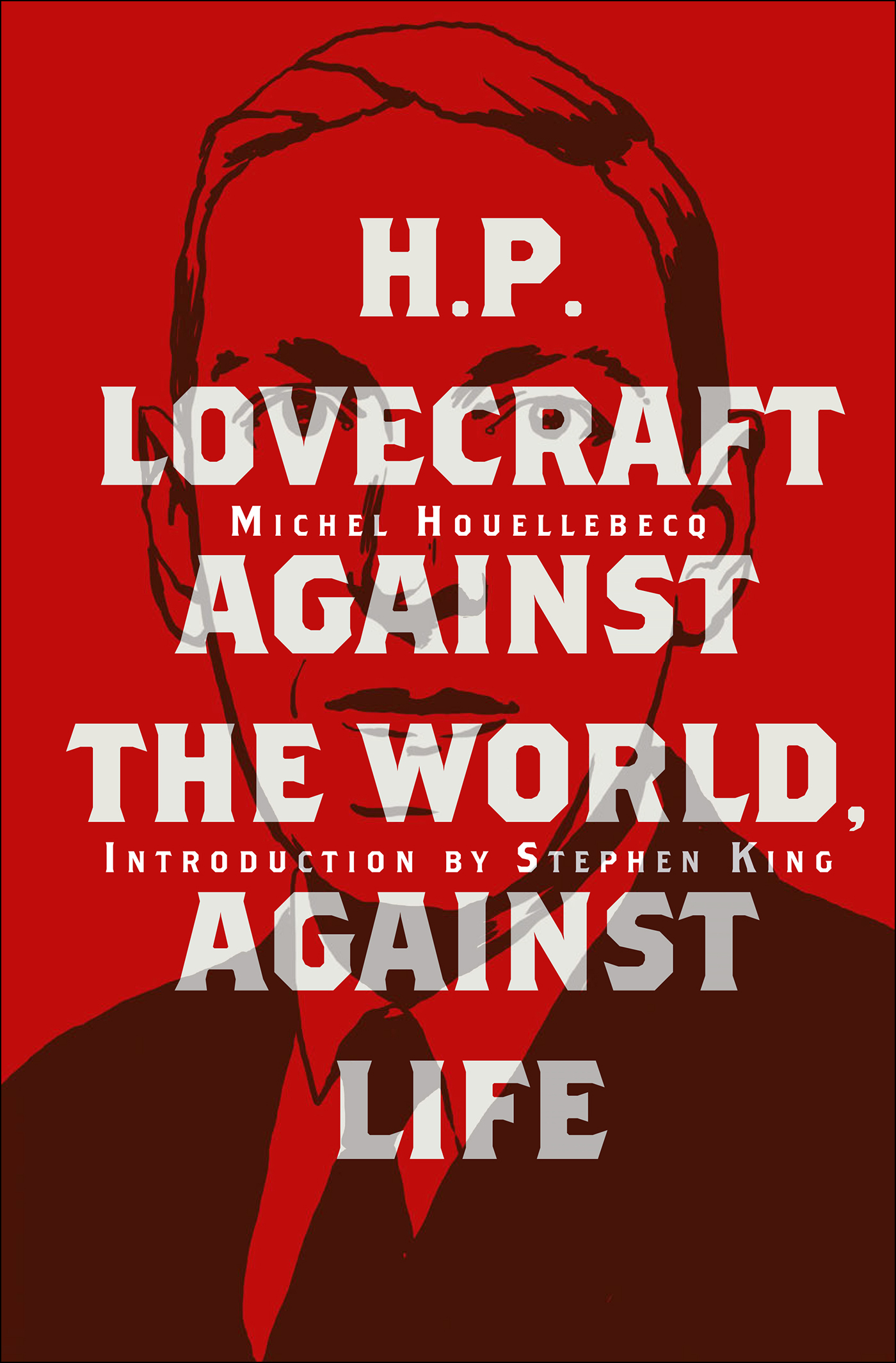

Michel Houellebecqs longish essay H. P. Lovecraft: Against the World, Against Life is a remarkable blending of critical insight, fierce partisanship, and sympathetic biographya kind of scholarly love letter, maybe even the worlds first truly cerebral mash note. The question is whether or not the subject rates such a rich and unexpected burst of creativity in what is ordinarily a dull-as-ditchwater, footnote-riddled field of work. Does this long-dead, pulp-magazine Johnson deserve such a Boswell? Houellebecq argues that H. P. Lovecraft does, that he matters a great deal even in the twenty-first century.

As it happens, I think he could not be more right.

Have you ever scared yourself?

Heres a question every writer whose work has touched upon the weird, the supernatural, or the macabre has been asked, not once but many times. I am sure that H. P Lovecraft faced the query, and that he replied with his customary gravity and politesse no matter how many times he heard it. Certainly he would never have answered as did one writer at a World Horror Convention I attended some years ago, with another question: Have I ever taken a piss?

Vulgar, that, but otherwise not a bad response. Because any writer who has worked this field of literature more than occasionally has scared him or herself. Men whove spent their lives in coal mines cough. Guitarists have calluses on the tips of their fingers. Deskmen and women often walk with a pronounced stoop by the time they reach middle age. These are occupational hazards. For the horror writer, the occasional scare when the imagination performs especially well is another. It comes with the territory, and most of us who work that territory consider a passing frisson no more interesting than the coal miner considers his cough, or the guitarist the tough spots on the ends of her fingers.

There is, however, a related question. Ask a group of writers who have specialized in tales of horror and the supernatural if theyve ever had an idea too scary even to write about, and their eyes will light up. Then youre no longer talking about occupational hazards, which is boring; then youre talking shop, which is never boring.

Ive had at least one such idea. It came to me while I was attending my first World Fantasy Convention, in the dim and antique year of 1979. That WorldCon happened to be held in Providence, HPLs hometown. While wandering aimlessly about on Saturday afternoon (and wondering, of course, if Lovecraft had once wandered the same streets), I happened to pass a pawnshop. The window was crowded with the usual bright assortment of goods: electric guitars, clock radios, straight razors, saxophones, rings, pendants, and guns-guns-guns.

While I was looking in at all this rickrack, Mr. Idea Man spoke up from his Barcalounger at the back of my head, as he sometimes does, and for reasons no writer seems to fully understand. maybe even the one he died on.

Reader, I cannot remembereven now, a quarter-century laterever having an idea that gave me such a chill. Lovecrafts pillow! The one that cradled his narrow head when he left consciousness behind! And Lovecrafts Pillow would, of course, be the title of my story. I hurried back to my hotel fully intending to skip everything else I had planned, two panel discussions and a dinner, in order to write it. By the time I arrived, a great many details about that pillow had come clear in my mind. I could see the slightly yellowish cast of the cloth; I could see a ghostly, brownish ring that might have been a tiny leakage of spittle from the corner of the thin-lipped, sleeping mouth; I could see a dot of darker brown that was surely blood which had slipped from one nostril.

And I could hear the low squeal of the dreams trapped inside. Yes indeed. The chittering of H. P. Lovecrafts nightmares.

If I had started the story right away, as Id planned, Im almost sure it would have been written, but as I was walking down the twelfth-floor corridor to my room, some hilarious soul popped out of another room, slapped a beer in my hand, and pulled me into a group of happy, promiscuously talking writers. Then came the panel discussions (after all), and the dinner (naturally), followed by a great deal more drinking (of course) and talking (to be sure). Not a little of the talk was about HPL, and I participated gladly, but I never did write that story.

Later that night, in bed, my mind turned to it again, and what had seemed marvelous in the afternoon light became awful to think about in the dark. It was thinking of his stories, you seethe ones that had been in that narrow head, horrors separated from the pillow by only the thinnest shield of bone. The best of themwhat Michel Houellebecq calls the great textsare uniquely terrible in all of American literature, and survive with all their power intact. Lovecrafts only stylistic rival at mid-twentieth century, ironically enough, may have been the noir writer David Goodis, whose language was entirely different, but who shared Lovecrafts inability to ever stop, to say enough is enough, but had that neurotic need to simply keep drilling away at the column of reality. Goodis, however, has fallen into obscurity. Lovecraft never did. And why not? I think because, unlike Goodis, the shrill pitch of HPLs compulsion was balanced by a kind of lumbering poetry and an unearthly range of imaginative vision. His screams of horror are lucid.

And was I, I wondered as I lay sleepless upon my own pillow, actually going to try and put all that into a story? The idea was ludicrous. To try and fail would be miserable. To try and succeed would require an expenditure of psychic energynot to mention simple nervefar beyond what any short story (save perhaps one by Gogol or Lovecraft himself) deserved. And the idea of trying to maintain such a gruesome conceit for the duration of a novel, even a short one, was too daunting for serious consideration. I felt like a would-be diver on the cliffs at Acapulco, who probably would have been all right if hed just gone ahead and jumped after a cursory look to make sure he was on the right side of the rocks. Instead, I paused too long to consider the drop and the possible consequences. Thus was I lost.