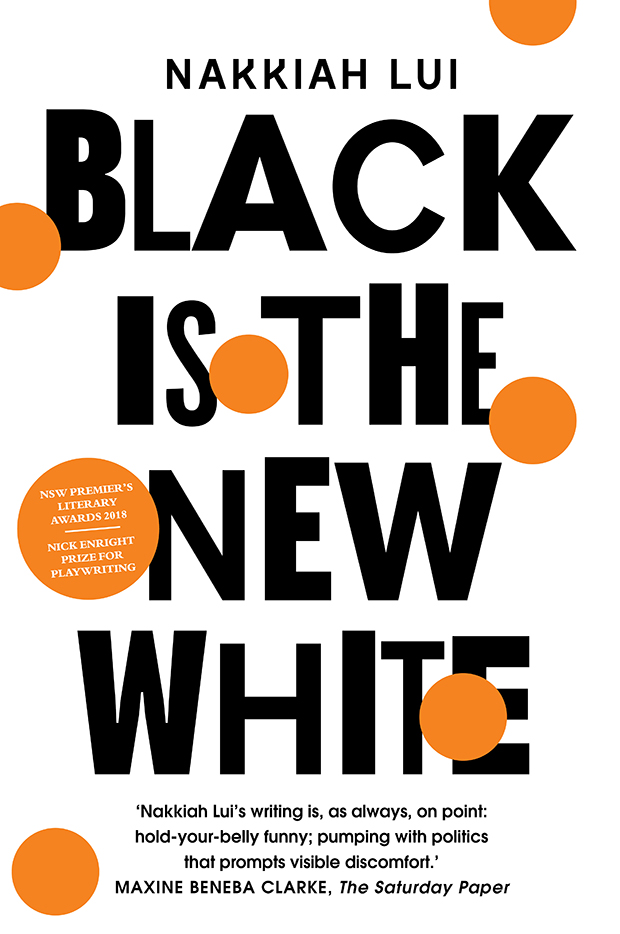

PRAISE FOR NAKKIAH LUI

Ive been in awe of Nakkiah since I saw her play This Heaven at Belvoir in 2013. I cant remember a time before seeing this play where I had seen Aboriginal people represented in the present day. Quite often the plays I had performed in or watched had been retrospective, and This Heaven spoke to me as a modern Black woman. I felt seen, I felt understood. Her work continues to explore what Aboriginality is in all its dimensions. My sister is brave, because you can always tell that she has spilled her heart onto the page. She is also insanely good at comedy, and uses that to challenge the privileges that colonisation continues to give non-Aboriginal Australians. She punches up by giving nuance and humanity back to her community. I loved playing Rose in Black is the New White not only because of all the great lines she gifted me, but also having the opportunity to perform with so many talented performers of colour. There were no egos on this project because everyone loved what they were a part of. I hope that audiences who see her work take whatever the play made them feel and do something to even the playing field for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Her work makes me believe that art can change the world. Miranda Tapsell

Sneakily disguised as a whacky Christmas rom-com comes this shrewd remoulding of the national chat about race in contemporary Australia. Its as if Nakkiah shows us our conversational display home, full of all those recliner rockers weve always retreated to in our discussions of race identity, and begins carefully rearranging them, and then picks them up and hurls them about the stage with savage glee. What a thrilling new voice in Australian theatre. Richard Roxburgh

Her writing, whether devastating or hilarious, has always shown a great deal of accessible humanity and relentless intelligence. The Guardian

We needed a new David Williamson, someone who speaks to Australia and Australians now. Weve found her in Nakkiah. Alex Broun

If there is such a thing as a rockstar playwright, Nakkiah Lui is it. Fran Kelly, ABC Radio National

First published in 2019

Copyright Nakkiah Lui 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email:

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

ISBN 978 1 76052 734 1

eBook ISBN 978 1 76087 042 3

Cover design: Alissa Dinallo

Internal design by Bookhouse, Sydney

For Joan.

For Jenny.

For Jack.

For Lowie.

For Keesh.

And most of all, for my silver lining of colonisation, Gabe.

CONTENTS

I love Christmas. My family love Christmas. I have never missed a Christmas with my family. That would be akin to some kind of sacrilege. I love the excitement you get from putting up the tree, singing along to Christmas carols that you only know two lines of. I love wrapping presents and trying to curl the ribbon just right. I love shopping with my family in the overcrowded shopping centres with their too-cold air conditioning and getting a kebab from the food court. I love the smells of cooking all day and getting dressed up to not leave the house. I love watching Christmas movies from the northern hemisphere that are filled with snow and cosiness, whilst I sweat it out in front of a fan. I love being with my family. A family that is changing as we get older, new members and additions joining each year and sometimes, sadly, a loved one leaving.

But Christmas isnt where the play started. Thats where the play ended up. Black is the New White started as two separate conversations. The first was about love. I was having a conversation with a cousin of mine who is this fabulous young Aboriginal woman, a gorgeous and great mum, a lover of Instagram and lycra and the hashtag #yummymummy. We were talking politics (talking politics is like talking sports in my family) and for some reason love came up, and she said that communities should try to stick together, to get bigger and better and Blacker her racial/political beliefs could be seen as akin to Black separatism and I didnt necessarily agree with her (I had dated one Aboriginal person and not had much luckthey turned out to be a cousin).

However, at the same time, both my parents are Aboriginal, same as hers, so why did she hold those beliefs and why didnt I? I thought it was a really interesting conversation to be having with someone who, I would say, is part of this new emerging Aboriginal middle class. It was around this time that I looked at the census and discovered a surprising statistic: 74 per cent of Aboriginal people who get married marry non-Aboriginal people. We were the community most likely to marry a race outside of our own. I found this really interesting it intrigued me as to who this 74 per cent are.

Primarily because I was one of them. I fell in love as I started writing this play. Id got engaged by the time it had finished. To a White man. I was part of this 74 per cent but that really bothered me, because, to me, my love was way more than a statistic. But there it was an overwhelming statistic that was vastly different to the trends of non-aboriginal Australians.

That led me to investigate how my own family had shifted over the last two generations, and how this had affected their definition of class. I was really interested in how we identify ourselves in terms of our racial and cultural backgrounds, and how that intersects with class. What does it mean to be successful? Especially as Aboriginal people, when you come from a community that is so often politicised.

I also wanted to present a family of Aboriginal people that hasnt been seen before, not just on stage, I would say, but within the canon of Australian artistic works. That is, an Aboriginal family who have money, who are not necessarily oppressed, but are culturally quite strong. So I had the idea of putting forth that family, because, for me, that was similar to what Ive grown up with.

The way my family has celebrated Christmas has changed over the years: from cold meat platters at my nanas tiny little fibro house we all crammed into before running under the sprinkler; big picnics with extended family in the local park as the kids ran around in what were called the piddle pools; then later, to hot meals with gourmet cuts of meat, caviar and Bellinis in the morning, swims in the pool in the afternoon; then, a white Christmas on the other side of the equator one year, together and loving Christmas in a foreign but familiar land.

But all still the same in the endwith your family, bickering and happy. The evolution of my family Christmas celebrations seemed to reflect a much bigger discussion I was trying to figure out: what is it to be Aboriginal and middle class? Is that even a thing?