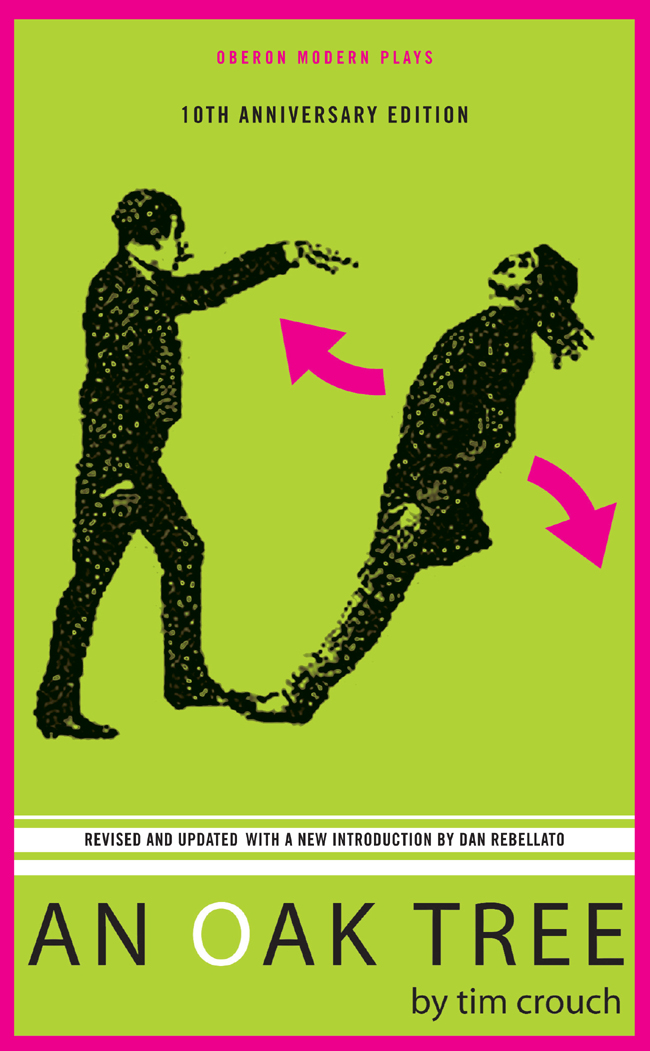

AN OAK TREE

Tim Crouch

AN OAK TREE

10TH ANNIVERSARY EDITION

UPDATED AND REVISED

WITH A NEW INTRODUCTION BY DAN REBELLATO

OBERON BOOKS

LONDON

WWW.OBERONBOOKS.COM

First published in 2005 by Oberon Books Ltd

521 Caledonian Road, London N7 9RH

Tel: +44 (0) 20 7607 3637 / Fax: +44 (0) 20 7607 3629

e-mail:

www.oberonbooks.com

Copyright Tim Crouch, 2015

Introduction copyright Dan Rebellato, 2015

Reprinted in 2006, 2011

Reprinted with revisions and updates in 2015

Tim Crouch name is hereby identified as author of this play in accordance with section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. The author has asserted his moral rights.

All rights whatsoever in this play are strictly reserved and application for performance etc. should be made before commencement of rehearsal to United Agents, 12-26 Lexington Street, London W1F 0LE (). No performance may be given unless a licence has been obtained, and no alterations may be made in the title or the text of the play without the authors prior written consent.

You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or binding or by any means (print, electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

PB ISBN: 978-1-84002-603-0

EPUB ISBN: 978-1-84943-583-3

Cover design by Julia Crouch

Printed, bound and converted

by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY.

Visit www.oberonbooks.com to read more about all our books and to buy them. You will also find features, author interviews and news of any author events, and you can sign up for e-newsletters so that youre always first to hear about our new releases.

Contents

INTRODUCTION

This book is a gallery.

Tim Crouch once described words as the ultimate conceptual art form. Words are strange things; they that can exist in an uncountable number of different forms, fonts, sizes, media; they can be spoken or sung or signed or written or printed or imagined; a handful of letters on a page can make you think, make you unreasonably happy, make you cry, and more; they can be invented anew, they can change their meanings, and they can peacefully die away; they can be chiseled into a gravestone and they can be impossible to get out of your head; they can describe the world and they can change the world. They point at concepts but are also conceptual things in themselves; like fairies in Peter Pan, they only exist because we believe in them.

And if the word is a conceptual art form, then this book which is full of them (go on, flick forward, its true!) is a sort of gallery of conceptual art.

Theres a tricky question buried in that description of words, which is about the relationship between words and the world. Words dont resemble the world they seem to describe. The word theatre doesnt look or sound like a theatre. Even onomatopoeic words dont sound all that much like the things they represent. So how do we come to represent the world through them?

This philosophical question is a practical question for the theatre. What is the relationship between a play on the page and a play in the theatre? Does the text define how the play must be done? If so, in what way and to what extent? If a playwright writes The FATHER nods his head, some parts of the stage picture are being defined, but others not. We dont know what the FATHER looks like, his height, how old he is, the colour of his hair, whether he has a beard, what hes wearing, his expression, and much more. We know that he nods his head, but not how: quickly? slowly? thoughtfully? eagerly? Is it a big vigorous motion or an almost imperceptible gesture? And just because the FATHER nods, does the actor have to? There are many ways of informing an audience that this has happened: someone could read the stage direction out; the gesture could be projected on a screen; it could be inferred from the way the HYPNOTIST reacts; or, if you like, the actor playing the FATHER could nod his head.

Sometimes, the theatre seems to forget that it has these choices to make. In some parts of our theatre, it will seem as if the actor nodding his or her head is the obvious or natural or correct or simplest or clearest or most real way to represent this direction. Since the late nineteenth century, British theatre has been in thrall to the view that the theatre should represent the world by trying to resemble it as closely as possible. This was not always the case; it would be a mistake to think that audiences at the theatre of Dionysus or at Shakespeares Globe sat there frustrated that they werent looking at more realistic scenery. In those theatres, it would seem, there was a clearer understanding that the theatre functions imaginatively: we are taken into a fictional world and whether that world is represented through realistic sets or random objects or words or sounds that evoke the imagination, these are still conceptual choices we have made.

An artist that Tim Crouch likes to refer to is Marcel Duchamp, one of the first artists to place concepts at the centre of his work, who made an important distinction between retinal art and conceptual art. Retinal art is grasped mainly through the eyes (on the retina); conceptual art is grasped with the mind. In fact, even in the most literal and realistic theatre show, there are always things that only exist for us conceptually; the past and future of the characters, the world offstage, the psychological states of people we are looking at. Most realistic theatre isnt all that realistic either: actors generally talk much louder than the characters would, walk about in rooms much larger than the characters would; to some extent we just choose to see them as realistic.

Tim Crouch puts the conceptual rather than retinal aspects of theatre front and centre but, in doing so, he reminds us that all theatre is like this. When, in My Arm (2003), he tells the strange story of the play using random objects gathered from the audience, we might well reflect that this is always the case; its to some extent arbitrary whether we represent a battle on stage by using onstage actors or offstage sounds or the words of a narrator or a short abstract physical sequence. When in ENGLAND (2007), he has the main character of the play represented simultaneously by two people, we might well reflect that all casting is to some extent arbitrary, that if we can accept young people playing old people or men playing women or poor actors playing Kings or, in the case of James Bond, several different people playing the same person, why should we insist that on stage one character must be played by one actor?

This might make An Oak Tree sound very abstract and airless. But its the opposite. What Tim Crouch and his collaborators understand is that the conceptual nature of theatre underpins all theatre from Antigone to Les Misrables, from Waiting for Godot to Run For Your Wife. You cant have fun or be moved or be filled with joy without partaking in the theatres conceptual playfulness.

Several apparently unusual theatrical devices structure the experience of An Oak Tree: first, in a beautifully childlike way, all of the theatres transformational power happens in front of us: