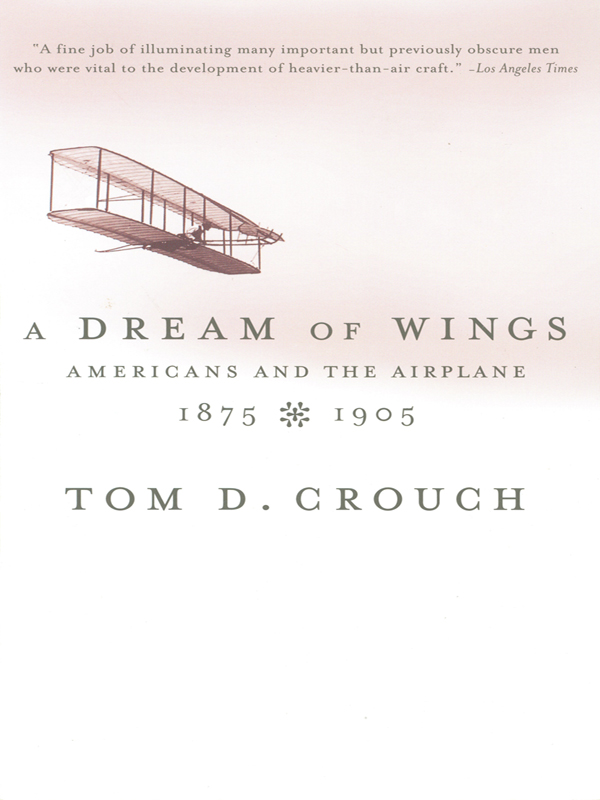

Tom D. Crouch

A DREAM OF WINGS

Americans and the Airplane

18751905

W. W. Norton & Company

New York London

Copyright Tom D. Crouch 1981, 1989

All rights reserved

First published as a Norton paperback 2002

All photographs are courtesy of the Library of the National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution. Portions of chapters 11, 12, and 13 have appeared previously in Smithsonian magazine, which has kindly given permission to reprint them.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W W. Norton & Company, New York, NY 10110

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Crouch, Tom D.

A dream of wings.

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

1. AeronauticsUnited StatesHistory.

I. Title.

TL521.C65 1989 629.1300973 88-26512

ISBN 0-393-32227-0 pbk.

ISBN 978-0-393-34745-6 (e-book)

W W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London WIT 3QT

For Nancy, Chris, Bruce, Abby, and Nathan with all of my thanks

Contents

It is good to have A Dream of Wings back in print. This book was originally intended to stand alone. It still does that, but Dream has also become the centerpiece of a trilogy. Having completed work on this volume in 1978, I turned my attention to the study of buoyant flight, producing The Eagle Aloft: Two Centuries of the Balloon in America (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1984). Those two books, taken together with a recent arrival, The Bishops Boys: A Life of Wilbur and Orville Wright (New York: W.W. Norton, 1989), present one scholars vision of the roots of American aviation.

Today I find it impossible to read Dream without recalling the extent of my indebtedness to old friends and colleagues. The original acknowledgments stand, but the appearance of this new edition affords the opportunity for additional thanks to a few individuals who have played special roles in the history of this book.

The study began as a doctoral dissertation supervised by Professors John C. Burnham and Merritt Roe Smith, with substantial assistance from Professor June Z. Fullmer. Edwards Park, then an editor with Smithsonian magazine, set in motion the process of transforming a dissertation into a book when he accepted the final chapter as a magazine article in 1978. Ed Barber, now vice-president of W.W. Norton, read that article and stunned its author with a phone call soliciting the entire manuscript for publication as a book. Almost a decade later, Felix Lowe, director of the Smithsonian Institution Press and himself a superb editor, went to considerable lengths to bring the volume back into print.

In one sense, this is a better book than the original. A few typographical errors are missing and some of the footnotes are less confusing. The basic text, however, remains unchanged. While I have learned a bit more about the subject over the past ten years, I am still content with evidence presented and the conclusions drawn by the much younger and less experienced scholar whose book this remains.

Acknowledgments

Any author who has worked for six years on a book will find it difficult to thank adequately all who have offered advice and assistance. In the case of this volume, which began as a doctoral dissertation and has undergone several radical alterations, the task is especially difficult.

Charles H. Gibbs-Smith and Marvin W. McFarland, the doyens of early aeronautical history, have read and reread the manuscript, offering the sort of friendship and helpful comment without which the volume would be poorer. Paul E. Garber has offered similar service of the sort that is impossible to repay. John C. Burnham and M. R. Smith served as doctoral advisers and guided the initial development of the work, F. C. Durant III, my supervisor during the course of the work, has offered consistent understanding and encouragement. Melvin B. Zisfein and Howard S. Wolko have answered patiently any number of nave questions on aerodynamics and aircraft structures.

My colleagues Richard P. Hallion, Claudia M. Oakes, and Donald Lopez have also read the manuscript and offered helpful counsel, while Eugene Emme and Thomas P. Hughes suggested basic alterations that improved the finished product.

A number of librarians and archivists have contributed to the project. Catherine Scott, Mimi Scharff, and other members of the NASM library staff have, as always, served as invaluable guides through the riches of their collection. William Deiss of the Smithsonian Institution Archive was of assistance in sorting through the Langley Papers. Father James McKevitt, archivist, University of Santa Clara, and the staffs of the Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, the John Crerar Library, the Cornell University Library, the Notre Dame University Library and Archive, and the National Archive also deserve thanks.

Others who have offered advice and assistance include Gregory Kennedy, Richard Hirsch, Mary Henderson, Rick Young, Phil Jarret, and Adrianne Noe. Phil Edwards of the NASM Library assisted in the selection of the photographs.

Special thanks go to Ivonette and Harold S. Miller of Dayton, Ohio. Mr. and Mrs. Miller, the Wrights favorite niece and the executor of their estate, opened their home to a young graduate student and patiently answered questions with friendship and hospitality. Octave A. Chanute and Elaine Chanute Hodges, relatives of another pioneer, have been generous with their time and friendship.

My wife Nancy and our children Christopher, Bruce, Abigail, and Nathan offered their support and understanding. Barbara Pawlowski put in long weekend and evening hours typing the manuscript and improving it in many respects. Ed Barber of Norton has been the most understanding of editors.

Huffman Prairie is a forgotten place of American history. A low stone marker commemorating the events that occurred here lies hidden behind a tall chain link fence that rings modern Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, where thousands of Air Force employees stream in and out of the sprawling aerospace complex each day. Yet it was at Huffman Prairie, a meadow set in the rich farmland of southwestern Ohios Miami Valley, that the old dream of aerial navigation became a reality for mankind.

Kitty Hawk had lured Wilbur and Orville Wright with the promise of ideal conditions for their aeronautical experiments. On the slopes of the Kill Devil Hills the Wrights had demonstrated in 1903 beyond doubt that their powered machine was capable of sustained flight under the control of a pilot. Nevertheless, they well realized that even the best performance of December 17, a straight-line flight of 852 feet in 59 seconds capped by a hard landing that damaged the forward skids and elevator, was scarcely calculated to convince skeptics that the age of flight was at hand. The brothers needed additional time to perfect their machine and to hone their piloting skills.

Next page