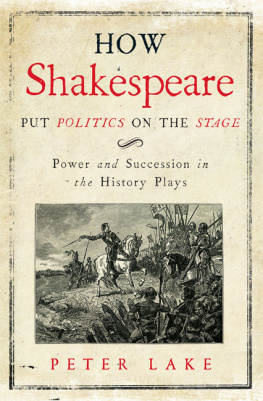

Tim Crouch

PLAYS ONE

My Arm

An Oak Tree

ENGLAND

The Author

OBERON BOOKS

LONDON

WWW.OBERONBOOKS.COM

This collection first published in 2011 by Oberon Books Ltd

Electronic edition published in 2012

Oberon Books Ltd

521 Caledonian Road, London N7 9RH

Tel: +44 (0) 20 7607 3637 / Fax: +44 (0) 20 7607 3629

e-mail:

www.oberonbooks.com

This Collection copyright Tim Crouch 2011

My Arm copyright Tim Crouch 2003, first published in 2003 by

Faber & Faber Ltd.

An Oak Tree copyright Tim Crouch 2005

ENGLAND copyright Tim Crouch 2007

The Author copyright Tim Crouch 2009

Tim Crouch is hereby identified as author of these plays in accordance with section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. The author has asserted his moral rights.

All rights whatsoever in these plays are strictly reserved and application for performance etc. should be made before commencement of rehearsal to United Agents, 12-26 Lexington Street, London W1F 0LE, (info@unitedagents.co.uk). No performance may be given unless a licence has been obtained, and no alterations may be made in the title or the text of the play without the authors prior written consent.

You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or binding or by any means (print, electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

PB ISBN: 978-1-84943-109-5

EPUB ISBN: 978-1-84943-519-2

Cover illustration by Julia Crouch

Printed, bound and converted in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd., Croydon, CR0 4YY.

Visit www.oberonbooks.com to read more about all our books and to buy them. You will also find features, author interviews and news of any author events, and you can sign up for e-newsletters so that youre always first to hear about our new releases.

To my friends Karl James and Andy Smith

a new adventure in a new idiomcalls for spectators who are active interpreters, who render their own translation, who appropriate the story for themselves, and who ultimately make their own story out of it. An emancipated community is in fact a community of storytellers and translators.

Jacques Rancire, The Emancipated Spectator

Contents

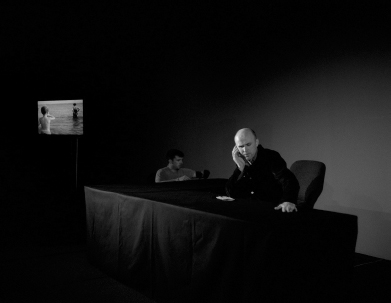

My Arm Hayward Gallery, February 2003

Chris Dorley-Brown

THANKS

All the people, theatres and galleries who have supported my work. All the second actors who have performed (and will perform) in An Oak Tree. Karl James and Andy Smith. Lisa Wolfe for producing me. Giles Smart and Nicki Stoddart at United Agents. Ruth Little, Mark Subias, John Retallack, Caryl Churchill, Peggy Paterson, Hettie Macdonald, Alastair Creamer, Thomas Kraus, Dan Jones, Hannah Reade, Hannah Ringham, Chris Goode, Adrian Howells, Esther Smith, Vic Llewellyn, Ben Ringham, Max Ringham, Alex Critoph, Pete Gill, Simon Crane, Chris Dorley-Brown, Jane Prophet and Michael Craig-Martin. Dinah Wood at Faber and Faber. Katherine Mendelsohn, Philip Howard, Dominic Hill and all at the Traverse Theatre. James Hogan, Charles Glanville, Andrew Walby, Sophie OReirdan, Melina Theocharidou and all at Oberon Books. Fiona Bradley and The Fruitmarket Gallery. Purni Morell and the National Theatre Studio. Dominic Cooke, Diane Borger, Kate Horton, and all at the Royal Court Theatre. Francisco Frazoa and Culturgest, Lisbon. Alan Rivett and Neil Darlison at Warwick Arts Centre. Kelly Kirkpatrick and Michael Ritchie at Center Theatre Group. Martin Platt and David Elliot at Perry Street Theatre in Exile. Stephen Bottoms and the Workshop Theatre, University of Leeds.

Julia Crouch. Nel, Owen & Joe. Pam and Colin.

Introduction

B ack in 1996, as a young critic shortly to publish his first book The Theatre of Sam Shepard the opportunity arose for me to meet John Lion, the founding artistic director of San Franciscos Magic Theatre. This was the venue where Shepard had premiered several of his most celebrated plays, so Lion was a key figure in the story. Not only that, he had read my manuscript, declared himself very impressed with it, and was promising a bang-up jacket blurb to help sell it (which he later delivered). I was excited to meet him, but fifteen years later I can recall little about our conversation other than the moment when he looked sternly at me and declared: You really need to put your dick on the table and say that Sam is the most important American playwright since Eugene ONeill. I nodded politely, and silently disagreed, but the phrase stuck in my head. Had something been lost in translation between Lions assertive, American masculinity and my awkwardly self-deprecating Englishness? Presumably, he imagined me thumping some huge lump of intellectual sausage onto his figurative table. Yet I, as an unknown twenty-something, couldnt help feeling that it would be more a case of small, pink chipolata.

Now, in my forties, and with a little bit more weight in the world, I am more than happy to well stick my neck out, and assert that the four Tim Crouch plays contained in this volume make up one of the most important bodies of English-language playwriting to have emerged so far in the twenty-first century. Of course, were less than a dozen years into it, so the statement is still a little on the cautious side, but I can think of no other contemporary playwright who has asked such a compelling set of questions about theatrical form, narrative content, and spectatorial engagement. These texts provide the outlines for an extraordinary series of live events, in which Crouch himself always performs, and which he has honed and developed in collaboration with his two, ever-present directors, Karl James and The published scripts cannot substitute for these theatrical experiences, as even a cursory reading of their opening stage directions should make clear: too much else is set in motion during performances of these plays for them to be adequately circumscribed by language. Nevertheless, the deft use of language in a perfectly phrased line, or a cunningly placed speech is one of the most vital, and under-appreciated, weapons in Crouchs dramatic armoury. These are plays that reward careful textual analysis, and their publication together will, I believe, help make that fact more widely appreciated.

It strikes me now that Lions dick on the table metaphor might help us begin to unpack some key features of Crouchs writing. Firstly, there is the sheer unexpectedness of the image. Had I been advised to stick my neck out (an overly familiar, and thus dead metaphor), I would probably have long since forgotten the whole exchange. Yet with a few simple words, Lion placed an image in my head that I havent been able to shake since (much as I might have wanted to). Part of that has to do with the incongruous juxtaposition of everyday elements (dick, table), part of it with the information that Lion had not provided (what size of dick, what kind of table), and part of it with the unspoken but disturbing possibility of other items in the scenic vicinity (a kitchen knife? a rolling pin?). My imagination was activated

![Blake Crouch [Crouch - Summer Frost [Forward Collection]](/uploads/posts/book/140601/thumbs/blake-crouch-crouch-summer-frost-forward.jpg)