FIRST IN FLIGHT

FIRST IN FLIGHT

Copyright 1995 by Stephen Kirk

All Rights Reserved

The paper in this book meets

the guidelines for permanence

and durability of the Committee

on Production Guidelines for

Book Longevity of the

Council on Library Resources.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kirk, Stephen, 1960

First in flight : the Wright brothers in North Carolina / Stephen Kirk.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-89587-127-0 (alk. paper)

1. Wright, Orville, 18711948. 2. Wright, Wilbur, 18671912. 3. AeronauticsUnited StatesBiography. 4. AeronauticsUnited StatesHistory. I. Title.

TL540.W7K57 1995

629.130092273dc20 95-6039

Design by Debra Long Hampton

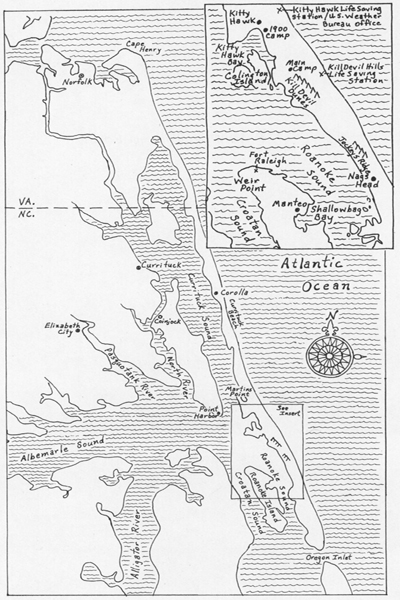

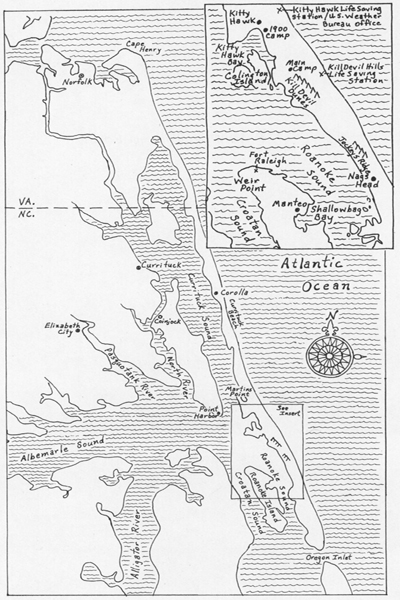

Map by Jonathan Phillips

Printed and Bound by R. R. Donnelley & Sons

To Mary, Elizabeth, and Rebecca

C O N T E N T S

The excerpts from Bruce Salleys 1908 dispatches included in this book appear courtesy of the Southern Historical Collection at UNC-Chapel Hill.

I owe thanks to many people for the help they provided during this project: the staff at Wright Brothers National Memorial, especially Darrell Collins and Warren Wrenn; Dawne Dewey at Wright State University; Steve Massengill at the North Carolina State Archives; Michael Halminski of the Chicamacomico Historical Association; Daniel W. Barefoot of Lincolnton, North Carolina, who generously shared unpublished material; Peggy A. Haile at the Norfolk Public Library; Steven Hensley of Greeneville, Tennessee; Barry Reynolds, southern Virginias baddest librarian; Jonathan Phillips of Wake Forest, North Carolina, mapmaker and friend; Marion Strode and Pamela C. Powell at the Chester County (Pa.) Historical Society; Monica Hoel and Thelma Hutchins at Emory and Henry College; Nellie Perry of the National Park Service; Doug Twiddy, Carole Thompson, and Jody Gibson of Twiddy and Company Realtors on the northern Outer Banks; the staff of the Maud Preston Palenske Memorial Library in St. Joseph, Michigan; Betty Husting of Locust Valley, New York; Thomas C. Parramore of Raleigh, North Carolina; Rodney Barfield at the North Carolina Maritime Museum in Beaufort; and Brenda ONeal at the Museum of the Albemarle in Elizabeth City, North Carolina.

The staff at the Outer Banks History Center in Manteo was of great help. Curator Wynne Dough gave my manuscript a careful reading. Hellen Shore and Sarah Downing answered numerous questions and located photographs for me.

Thanks is also due Judy Breakstone, Sue Clark, Margaret Couch, Debbie Hampton, Liza Langrall, Carolyn Sakowski, Anne Schultz, Dr. Heath Simpson, Lisa Wagoner, and Andrew Waters at John F. Blair, Publisher.

Lastly, I should credit my mother, Pat Kirk, whose interest in books inspired mine; my father, Ed Kirk, who got close enough to Chuck Yeager to actually reach out and touch him, but wisely refrained from doing so; and my wife, Mary, and daughters, Elizabeth and Rebecca, for their support through more than a few lost weekends.

Admittedly, this is the kind of book Orville Wright wouldnt have liked.

During his later years, a number of writers went to great lengths to win his approval for their biographies of the Wrights, the primary results being hurt feelings and even an attempt by Orville to pay one writer to kill his project. It took Fred Kelly, the Wrights authorized biographer, more than a quarter-century to earn Orvilles confidence.

The rub was always Orvilles insistence on separating the invention of the airplane from the personality of its inventors. He wanted the story to be heavy in technical explanation and light on personal detail. As far as he was concerned, the development of the airplane was a tale fraught strictly with engineering hurdles, but contrary to his wishes, the public found the image of two self-taught geniuses in suits and stiff collars chasing gliders in the dunes as appealing as the invention itself.

Neither does this book attempt to do justice to the career of the Wright brothers.

Experts agree that their experiments in Ohio, Virginia, and Europe were more important to the development of aviation than what they did on North Carolinas Outer Banks, the focus here. But just as the Wrights personal traits had a definite bearing on the solution of the flight problemwhether Orville liked it or notso did the Outer Banks exert an influence on the Wrights. It is far from certain they would have succeeded elsewhere.

I got the idea for this project upon seeing a photograph captioned Worlds First Flight Crew in an old book I bought for twenty-five cents at a library sale. The photograph showed seven mustached, hard-looking men of the United States Lifesaving Service standing before a plain wall. These were men whose job it was to guard the welfare of sailors along one of the most dangerous sections of the Atlantic coast. As a sidelight, they gave aid to a couple of visiting bicycle builders and posed for their camera, looking about as natural as figures in a wax museum. I wanted to learn how these men found themselves parties to one of the great events of the century; how their lives were affected when the Wright brothers came to town; how their help, along with that of other local residents and a variety of visitors to the Outer Banks, figured in the Wrights success.

People like Dan Tate, Augustus Herring, Alf Drinkwater, and Bruce Salley are remembered only as footnotes to the Wright brothers storywhen they are remembered at all. But that is not to say they have no stories to tell. One ten-year-old Kitty Hawk boy went aloft in a Wright brothers glider nearly two years before Orville Wrightthe worlds first heavier-than-air pilotever did. One local man was so well respected by the Wrights that he remained in contact with Orville for more than four decades after the famous flights. Others parlayed a rather scanty association with the brothers into fame and public appearances. One of the early aeronauts who witnessed the Wrights experiments on the Outer Banks was distinctly unimpressed, disparaging them as mere bicycle mechanics to his dying day. Another started out their friend and ended up claiming they appropriated some of their most important ideas from him.

Pieces of the Wrightsa sewing machine, bits of wing fabric, the wood from their camp buildings, papers they left behindare scattered around the Outer Banks, in fact and legend, well beyond the bounds of Wright Brothers National Memorial.

This book seeks to describe the full range of the Wright brothers experiences on the Outer Bankstheir experiments, their leisure-time pursuits, the lifesaving personnel and local citizens they associated with, the other outsiders who came hoping to fly with them or cover them in the press. It also seeks to present the Wrights trips to North Carolina in the broader context of what was happening on the Outer Banks at the turn of the century. Other events of note took place while the Wrights were in residence, including the ground-breaking work of another experimenter, now as obscure as the Wrights are famous, who changed the world nearly as much as did Wilbur and Orville.

If the Wright brothers story can be boiled down to one essential fact, it is that on December 17, 1903, they made four powered airplane flights at Kill Devil Hills, North Carolina, the first in history. But depending on how far you care to read into dubious sources, you can find that they made three flights that day, or only one, or that they flew successfully three days earlier, or that they never left the ground at all until 1908. And that doesnt begin to examine the claims of people who counted themselves responsible in some way for the brothers success. There is no part of the Wrights story that hasnt been disputed by someone.

Next page