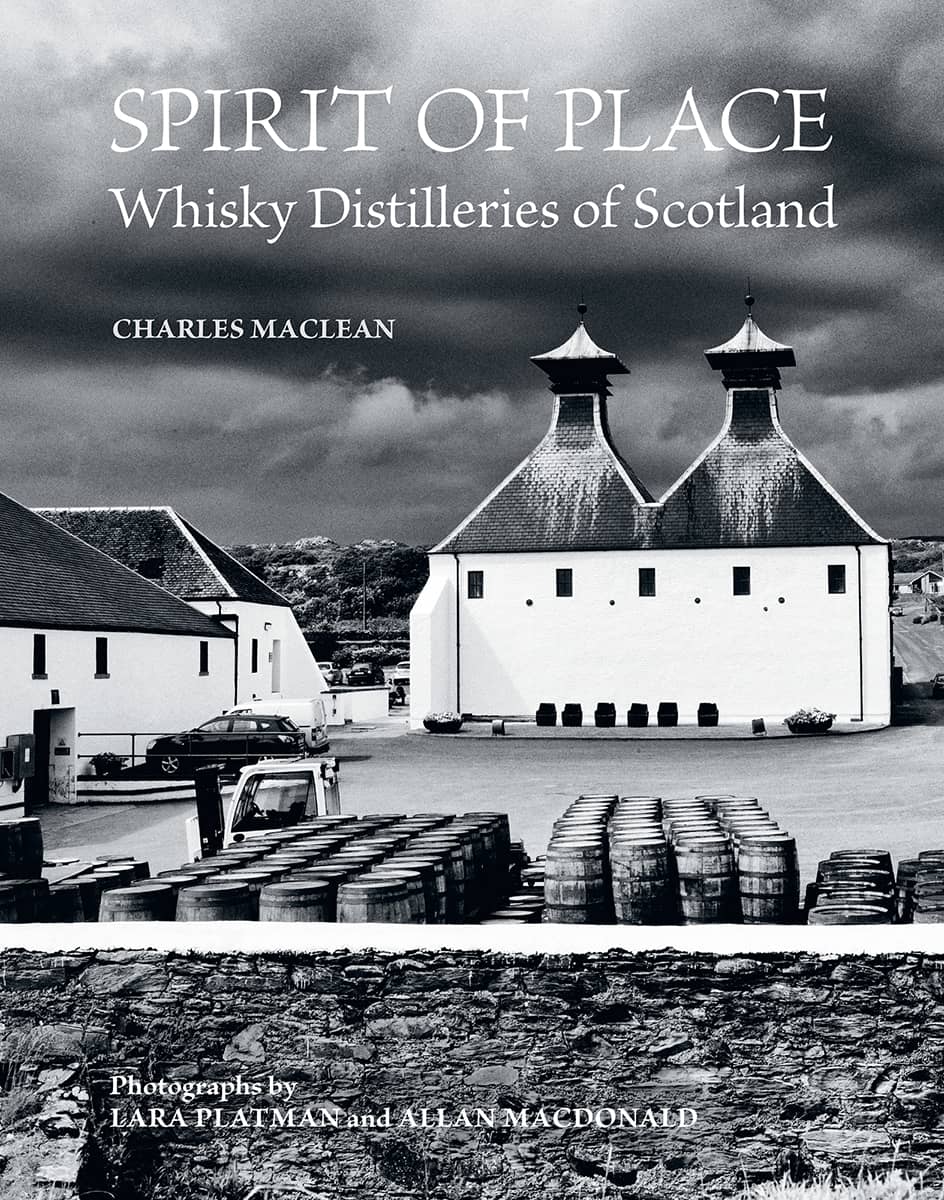

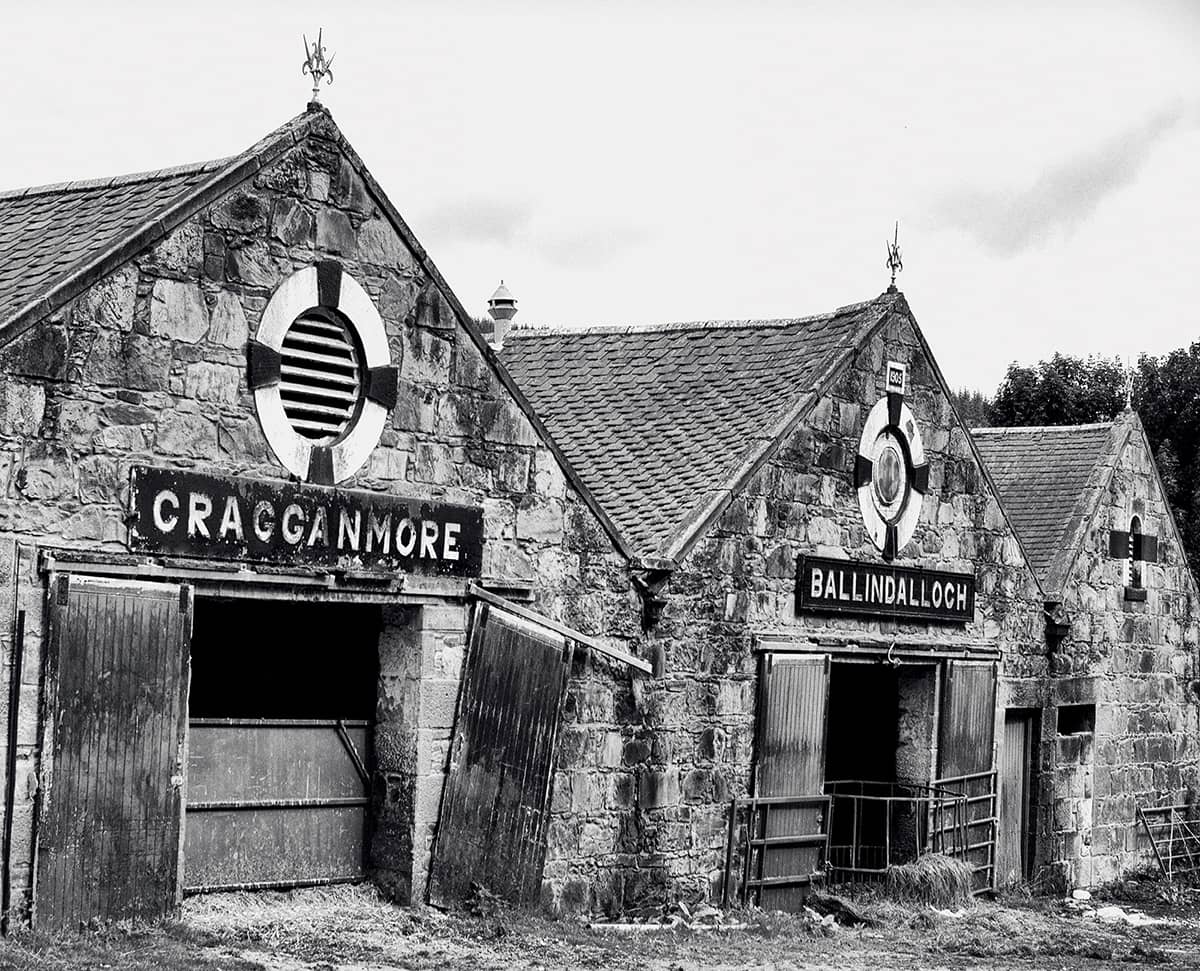

SPIRIT OF PLACE

Whisky Distilleries of Scotland

CHARLES MACLEAN

Photographs by

LARA PLATMAN and ALLAN MACDONALD

INTRODUCTION

I have long maintained that malt whisky is the quintessence of Scotland. For me, it conjures the land of its birth in all its seasons with every sip flowering machair in spring, warm beaches and heather pollen in summer, wayside berries and orchards in autumn, and the reek of winter peat (reek here being the term for distillers use to describe peat smoke). The smells of cooking and baking, childhood sweets, leather upholstery, grandpas motor car, church candles, cut grass, meadows, pine forests, sawn timber the aromas called to mind are rich indeed.

The associations I make are necessarily personal and are usually associated with smell rather than taste. It is well known that, of all our senses, smell most rapidly and effectively stirs long-term memory, but with a little imagination, the images arise like friendly phantoms to enhance my appreciation of the dram in my glass.

As my friend, the songwriter Robin Laing, puts it in one of his songs: Its the pulse of one small nation so much more than just a dram [evoking] the people and the weather and the land: the past distilled into the present.

Another friend once said: When you buy a bottle of whisky you are buying an awful lot more than liquor in a bottle. You are buying history and high craft; tradition and experience; all the time that has gone into the making and the maturing.

Malt whisky does more than evoke the place in which it is made it arises from it. According to whisky philosopher Dave Broom, Scotlands landscape has formed the industry in multifarious ways, from dictating where distilleries could be built, offering places to hide and then places to prosper There is even the tantalising possibility that early distillers tried to capture the vivid scents of hot gorse, fresh flowers, heather and bracken in their whiskies. He describes this as cultural terroir. Elsewhere he expands the notion, explaining that life in the Highlands is a compromise between man and land, and suggests that many fail in their enterprises because they forget that the land has the upper hand. Whisky, however, has survived and continues to thrive because it is pragmatic. Broom says that it is as though the distillery workers have concluded that whisky making is something that they can do in this environment and whats more, because we have done it for generations it reflects where we are, who we are and what we make.

It is an interesting concept. When French winemakers use the term terroir, they do so to describe the profound influence of geography, climate and geology upon the flavour, style and quality of their wines ultimately to describe the very soil in which their grapes grow. The concept cannot be applied in precisely the same way to whisky distilling, but it does appear that somehow the subtle influences of local geography, combined with tradition, process and plant, act to differentiate the whisky made in each distillery and every region of Scotland, in ways that are still not fully understood by science.

Regional differences

In the 1980s it became common to discuss malt whiskies in terms of regional differences, on the basis that the malts made in one part of Scotland are different to those made in another. This was really no more than a brilliant marketing idea, but it almost accidentally communicated a real fact that all malts are different in a way that is familiar to wine drinkers, who are used to the idea of differences within and between regions.

This idea of regional difference has also been justified by the existence of a division between Highland and Lowland regions, even though this was first introduced for tax reasons in 1781. A natural identification with region also occurred among blenders of different styles of spirit, who thought in terms of malts from Islay, Campbeltown and Speyside (originally Glenlivet).

There is no way of pinning down the difference for sure and perhaps the blenders tastes have owed more to tradition and the requirements of their blending houses when buying, as those firms were (and are) the key customers for malt whisky. Today, Islay style malts are being made on Speyside and Highland style on Islay. So beware of thinking that all Islay malts are smoky or all Speysides are fruity. Notwithstanding this, allow yourself to notice the flavour profiles that do seem to attend to a particular region.

MAKING MALT WHISKY

Many of the photographs in this book relate to aspects of the production and maturation processes, so I will run through these processes, in relation to how each might influence the flavour of the mature whisky.

Raw materials

By law, malt whisky may be made only from malted barley, water and yeast. Scotch malt whisky must be distilled, matured and bottled in Scotland. Barley, one of the first cereal grains to be cultivated, has been grown in Scotland since Neolithic times. New strains or varieties are continually being developed with a view to increasing yield (the amount of alcohol per tonne of grain) and ease of processing. The general view of the whisky industry is that the barley variety does not have much influence on the flavour of the spirit, but some dispute this.

It used to be thought that the nature of the water used for mashing (the process water) was crucial; that it was the water which differentiated one make from another. The general view among Scottish distillers today is that the mineral content and pH value of the water make little difference to the flavour of the mature spirit, although, again, some distillers beg to differ.

There is a similar debate about yeast. Traditionally, a mix of brewers and distillers yeasts were used and it was believed that brewers yeast contributed fruity flavours. Today, brewers yeast has been abandoned without, it is said, affecting flavour. This surprises American and Japanese distillers, for whom the yeast strain is considered fundamental.

Malting

Malting is the process by which cell walls in the barleycorns are broken down so that the starches contained in the cells may be converted into sugars. The sugars, in turn, will be converted into alcohol during fermentation. In nature, this process occurs when the seeds sense that it is time to germinate: the starch is present in the seed, ready to feed the young plant until it has put down roots and sprouted. The malting process imitates this in a way, it tricks the seeds into thinking that spring has arrived and it is time to burst into life and start growing.