1

GETTING LOADED

It is late Saturday morning, and my mother is at the stove fishing the doughnuts out of a dangerous pot of boiling fat. My father is quietly watching her while sipping on an instant coffee and tapping his spoon on the can of Carnation evaporated milk. The top of the can is punctured by two triangular holes, and one has a collar of yellowing acrylic scum. He puts the spoon on the table and reaches past her, plucks a new doughnut from a heaping plate, rolls it around in the sugar bowl, nibbles delicately. His thinning hair is dishevelled, his eyes watery.

Every so often a fella needs a good blowout, he says.

The reference is to last night, when we got loaded. Now hes either still half in the bag or hes getting reckless in his old age. That might be what a little bit of good luck does to a man who never had much. Im thinking: he isnt reading the room; he isnt picking up the signals.

Im in the rocking chair near the corner of the stove, maintaining a tactical silence.

Theres the rasping rattle of spitting fat. Another plate of dough balls slides into the bubbling cauldron. I imagine the quiet invocation of spells.

I light a cigarette and, when my mother disappears briefly into the pantry, quietly propose taking our hangovers to town, where they are less likely to become a topic of conversation. The house is too warm anyway. It is November, but a fat fly is stirring on the window ledge.

The old man shrugs, drains the mug, coughs deeply, then agrees.

Well check out the town. Postpone the reckoning.

He winks at me.

I hadnt seen the town for a year, not since moving the family up to Ottawa, where I have a job on Parliament Hill working for a newspaper. It was a paper I knew nobody around here ever saw because it was all business and finance. You could feel a palpable difference from before, when I was with the Halifax daily and the locals regularly followed what I wrote. It was like having a thousand editors thenevery one of them with an opinion, particularly on the politics. But after I went to Ottawa in the fall of 67, it seemed Id moved to another planet.

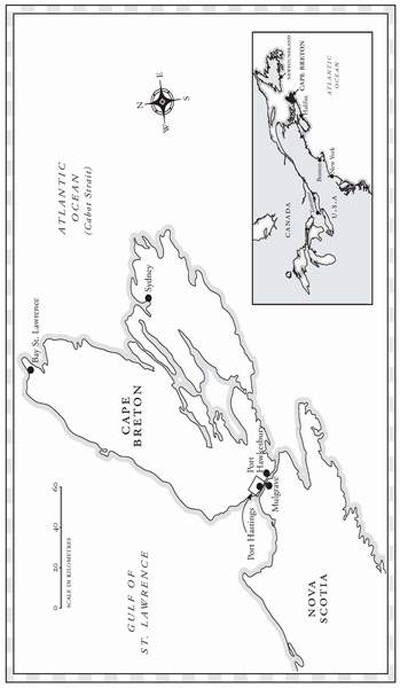

The trip home had been unexpected. Mid-morning the previous day I got a call from a buddy in a ministers office offering a free lift down. MacEachen and Chrtien had government business in Cape Breton on the weekend. There was a spare seat on the government plane, leaving early evening.

I called home in the middle of the afternoon. The old man promptly volunteered to meet me at the airport in Sydney, two hours away. It was Friday night, and all the liquor stores were open late.

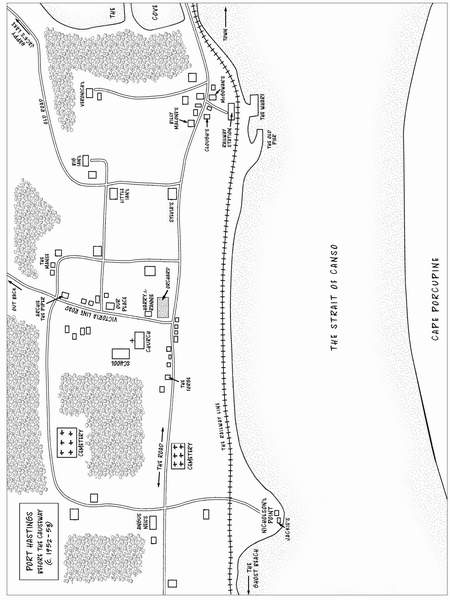

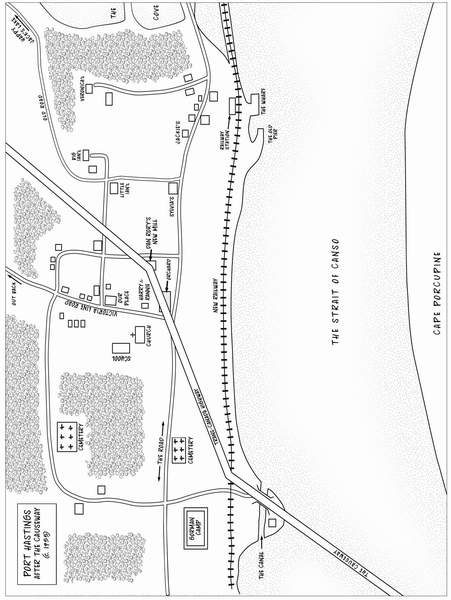

Driving towards town, I couldnt miss all the changes. The village I grew up in, Port Hastings, and the town, Port Hawkesbury, three miles away, seemed to be in a permanent state of turmoil. Mostly stuff was being torn down to make way for new roads, by the look of it. Houses gone. Roads widened, menacing even the old stores that have been here forever, Cloughs and McGowans. Also the old Captain MacInnis house, where my friend Billy Malone lived for a while. Even Mr. Cloughs lovely old home. All landmarks, and all under the soulless shadow of progress.

Its hard to believe Mr. Clough has been dead for almost a decadesince 59. They say it was the Diefenbaker sweep of the country in 58 that did it, just two years after the Stanfield Tories snatched power from a bereft Liberal Party in Nova Scotia. It was all too much for himtwo Tory victories in quick succession. Three, actually: Diefenbaker won a minority first, in 57. Then he practically exterminated the federal Grits in 58. Mr. Clough was gone a year later.

Other Liberals would scoff, of course. Mr. Clough was almost eighty, for the love of God. And he had wicked ulcers, anyway. Always optimistic about the future of the place was Mr. Clough. Yes, hed probably have given up on the whole Western world, seeing Diefenbaker in power. But that would have just made him more determined to live and work like the patriot he was to put a quick end to that anomaly of Canadian historya Tory majority government in Ottawa.

Who knows with politics?

Just beyond the town, in another old village called Point Tupper, there was a large Swedish wood-pulp mill, and it was about to expand into newsprint. There was talk of other big projectsan oil refinery; petrochemicals; a dock for the largest supertankers in the world; a heavy-water plant that would have something to do with nuclear power. Point Tupper was doomed, but nobody except for a few of the older people there seemed to care. Port Hastings and Port Hawkesbury were the beneficiaries.

It was becoming very exciting, but the main headline was that out of all the commotion and progress, the old man had finally scored the first dependably permanent employment hed ever had in what he would call civilization. He was fifty years old. He was born on a mountain just out back. He grew up around here and had his own family and home here for years. But to support himself and us hed spent most of his adult life living in wilderness camps all over the country and working as a miner, an occupation hed begun shortly after he turned sixteen, back in what they called the dirty thirties.

The new job, hed explained the night before, was not exactly what he wanted to do with his life, but it was a definite improvement over the miseries of mining camps and long days blowing up rocks in the impenetrable darkness far below the surface of the earth. A steady, well-paid job in the fresh air, it was, good enough for the time being.

Who is it again youre working for? I asked.

The Nova Scotia Water Resources Commission, he replied grandly, half mocking the long, vague title.

But it was good workmostly driving around in his new Volkswagen checking out pipes and pumps and valves and keeping an eye on Landry Lake, the water resource that supplied all the new industry and the expanding town.

It all sounded very boring.

What else did we talk about?

Briefly, my newspaper work, which has to do with government policy and the balance of payments, interest rates, and a lot of abstract economic indicators that seem to reveal the future to the knowledgeable. I told him a bit of inside stuff about the Cabinet ministers on the plane. Allan MacEachen, minister of immigration, is also the local MP and, just months earlier, ran against Pierre Trudeau for the party leadership. And a relative unknown, Jean Chrtien, is in Indian Affairs, but, coming from Quebec, is a stranger hereabouts.

Just ordinary fellows, I told my father. Plain guys like ourselves. Wed all had a couple of drinks together coming down on the plane.

Speaking of drinks

Sure, he said.

Drinking in the car was pretty normal then, and by Kellys Mountain the conversation was quite animated, even if not particularly meaningful. But I could clearly remember that there was a lot of talk about being your own boss, which was a dearly held dream of his from the year naught. Much like writing The Great Canadian Novel was a dearly held dream of younger fellows in the press gallerysomething you talked about when you were loaded, and rarely even then.