MEMOIRS

of a

CAPE BRETON

DOCTOR

Dr. C. Lamont MacMillan

Copyright The Estate of Dr. C. Lamont MacMillan 1975, 2010

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission from the publisher, or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, permission from Access Copyright, 1 Yonge Street, Suite 1900, Toronto, Ontario M5E 1E5.

Nimbus Publishing Limited

PO Box 9166, Halifax, NS B3K 5M8

(902) 455-4286 nimbus.ca

Printed and bound in Canada

Cover design: Heather Bryan

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

MacMillan, C. Lamont (Carleton Lamont), 1903-1978

Memoirs of a Cape Breton doctor / C. Lamont MacMillan.

ISBN 978-1-55109-757-2

EPUB ISBN 978-1-55109-841-8

1. MacMillan, C. Lamont (Carleton Lamont), 1903-1978.

2. PhysiciansNova ScotiaCape Breton IslandBiography.

I. Title.

R464.M27A3 2010 610.92 C2009-907327-7

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP) and the Canada Council, and of the Province of Nova Scotia through the Department of Tourism, Culture and Heritage for our publishing activities.

CONTENTS

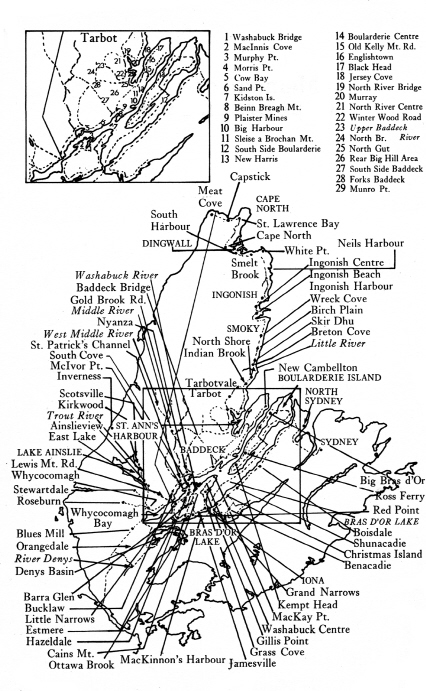

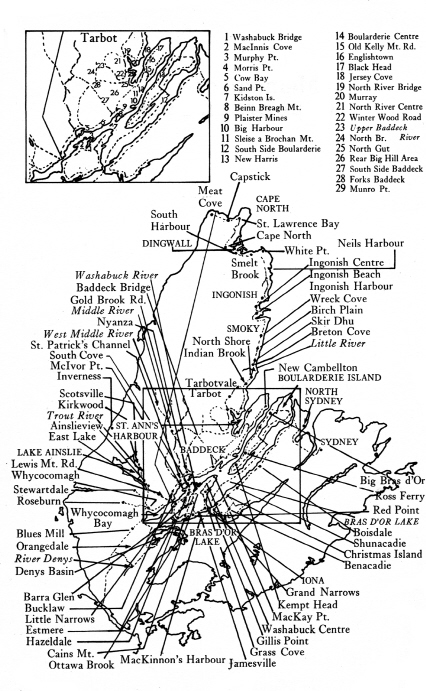

M any years ago I was hunting in the Rear Big Hill area of Cape Breton. Before the turn of the century, this area had been heavily populated. By the time I opened my practice in Baddeck in 1928 there were only three families living there. Now there is no one.

While walking through the woods, I found myself in an area so thick with underbrush I had to get down on my hands and knees and crawl, pushing my gun ahead of me. Suddenly I realized that I was in an old burial ground, with tombstones all around me. Here was all that remained of a once flourishing community. Each tombstone told its story. Many marked the last resting places of children and young adults. As I read the names and ages at time of death, I conjured up in my mind pictures of the homes where those people lived, the suffering they had endured, the helpless anguish of their families. I found myself wondering, What was the cause of death? Did these young people have any medical care? Could a doctor have helped them?

I wondered, too, about the doctors who had served the early settlers. During my own practice I encountered many of the same difficulties those early doctors must have faced. Often the most difficult part of my work was reaching the patient in the back country. Today Cape Breton has fine modern roads, and even the secondary roads are kept plowed in the winter. But as recently as twenty years ago I answered winter calls by horse and sleigh, snowshoes, or on foot across frozen lakes or bays.

Those early doctors must have been rugged men indeed. Unfortunately, little is known about them. I can understand why they left no records. When a single call may involve miles of travel by horse or on foot and take several days, there just isnt time to keep a journal.

I left this pioneer graveyard very saddened, but I realized, too, that most pioneer graveyards told the same story.

Some of the old-timers had stories of the doctors who preceded me. Ive collected all the information I could find about these early doctors, both from official records in the Nova Scotia Archives and from the oral history of this region, the stories passed down from one generation to another. Their story is an important part of our heritage and deserves to be preserved for future generations.

I want to thank all of my friends of Victoria County who have shared their memories with me to make possible this reconstruction of a way of life. Being a busy country doctor for so many years didnt prepare me for scholarly biography. If I have done this well, it is because of the unselfish aid given me by my friends. I acknowledge the help from Mr. Sydney Maslem when this narrative was taking form. I thank Mrs. Pamela Newton for her advice during that difficult period when I was cutting the book down to an acceptable size. Finally my thanks go to Mrs. Dorothy Holman for her help in bringing the book to its final form before it went to the publisher.

T he year 1784 saw the Island of Cape Breton separate politically from the mainland of Nova Scotia and become a new province. Grants of land were available to new settlers as never before, and many immigrants, deported from the highlands and islands of Scotland, took advantage of them. For the most part, these new citizens settled in rural Cape Breton. When they landed, their possessions were very few, their sufferings and privations unimaginable. Physically and psychologically they suffered for want of adequate medical servicesthere were none except in the Sydney and Arichat areas, and with transportation as it was then, Sydney and Arichat were a long way from all rural communities. Those of us who have visited a pioneer cemetery are saddened by the death of so many young people. I always wondered how many could have been saved to live out a normal span of life if they had had medical services. But rural Cape Breton saw many years without trained medical personnel.

The Clergy, especially the Presbyterian ministers sent out from Scotland as missionaries, had studied some principles of medicine during their college course. They regarded it as part of their ministerial duties to attend to the health of the people entrusted to their spiritual care. It was as important to ask about the Epsom salts, sulphur and molasses as it was to answer correctly, What is effectual calling? But these clergymen also probed deeply into the moral nature of their flock. And this attention to virtue, I have no doubt, produced results that made for the inculcation of those virtuous habits that redound to the health of the individual.

Traveling on horseback, winter and summer, along primitive paths in the forests, these ministers let nothing deter them from their monthly visits. The late Frank McGregor of Nyanza had a story about those early years, when all homes in the country had a spare bedroom downstairs that was always ready for any guest, especially the minister on his monthly call. It was the custom in winter to send the maid to that bed early in the evening to warm the bed. When bedtime came, the hostess would awaken the maid and send her to her own room. In those times the Scottish clergy were not against a little good Scotch whisky on a cold winter night just before bed. On one occasion the wee drop must have been repeated, because the hostess forgot to wake the maid. The minister was given his candle, and he started for the spare bedroom. When he opened the door and saw the beautiful girl in bed, he raised his candle a little higher to make sure and said, Oh Lord, the companionship was good, the prayers were good, the whisky was good but this is certainly the height of highland hospitality!

In every little community in rural Cape Breton there was a dedicated body of women known as grannies or midwives. They were not graduates of any institution but learned their trade in the school of experience. In maternity cases they knew how to support the baby when it was being born, how to clear any mucus in the babys air passage, and how to tie the cord. For most births they moved into the household and did the housework, as well as looking after the mother and baby. Sometimes they even helped with the barn work. For many years after medical services were available to rural Cape Breton, the doctor was called in only when there were complications. The midwife was called first, and it was she who decided whether it was necessary to call the doctor.

Next page