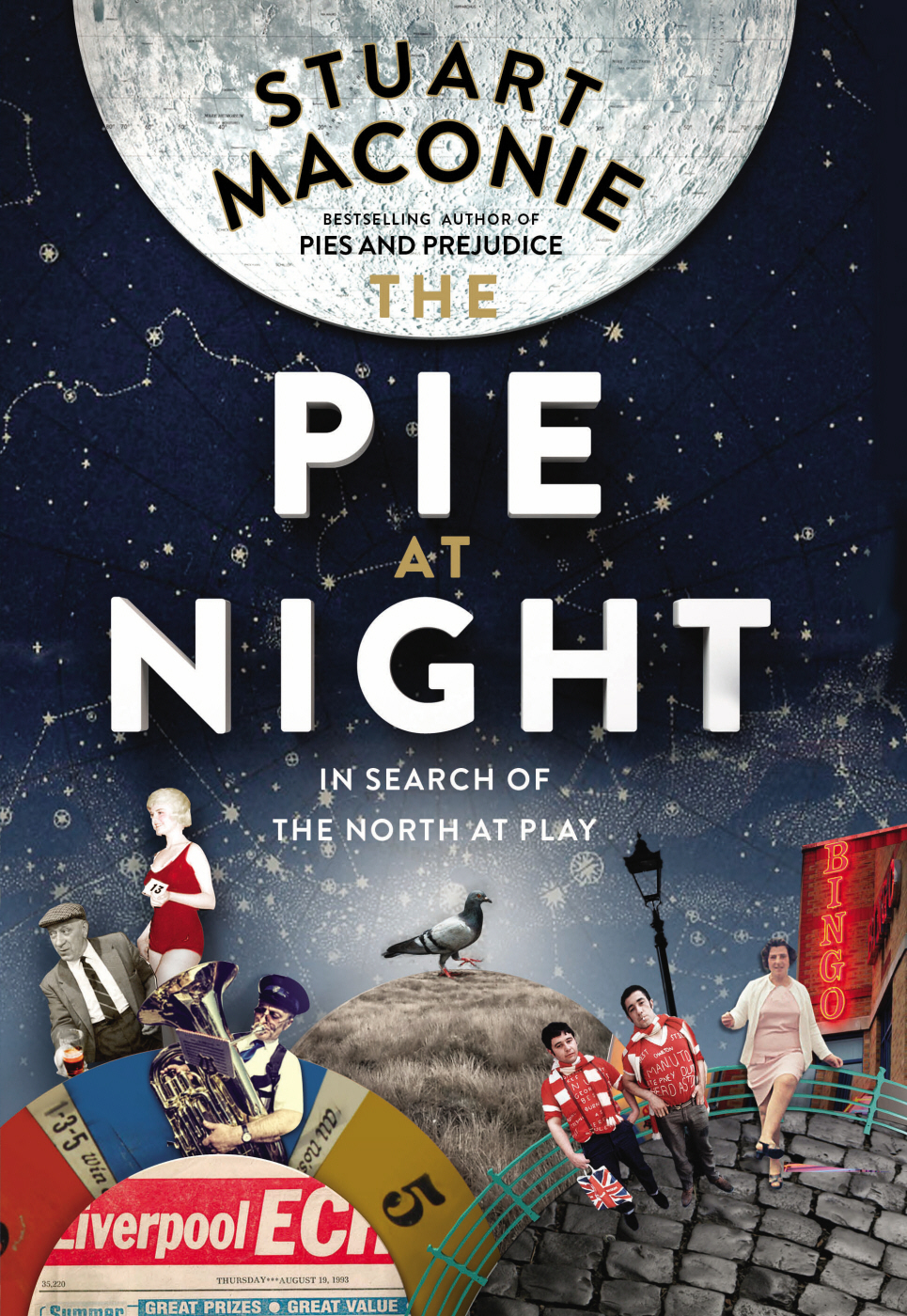

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

CLOCKING OFF

CHAPTER ONE

PLAYING AT WORK

CHAPTER TWO

LIVING THE SPORTING LIFE

CHAPTER THREE

HAVING A FLUTTER

CHAPTER FOUR

GETTING A BIT OF CULTURE

CHAPTER FIVE

HAVING A GOOD FEED

CHAPTER SIX

MAKING A DAY OF IT

CHAPTER SEVEN

KICKING A BALL ABOUT

CHAPTER EIGHT

GETTING A BIT OF FRESH AIR

CHAPTER NINE

STRIKING UP THE BAND

CHAPTER TEN

TRYING SOMETHING A BIT DIFFERENT

EPILOGUE

DRINKING UP

Also by Stuart Maconie

Cider with Roadies

Pies and Prejudice

Adventures on the High Teas

Hope and Glory

The Peoples Songs

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Epub ISBN: 9781409033240

Version 1.0

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Ebury Press, an imprint of Ebury Publishing,

20 Vauxhall Bridge Road,

London SW1V 2SA

Ebury Press is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright Stuart Maconie 2015

Lyrics to Duw Its Hard used by kind permission of Max Boyce

and Rocket Entertainment

Text from Why doesnt Britain make things any more? by Aditya Chakrabortty

Guardian News & Media Ltd and used with kind permission

Morning, Noon and Night by Philip Larkin the Estate of Philip Larkin

reproduced by permission of Faber and Faber Ltd

Text from Giles Corens review of Aumbry, Manchester The Times

used with permission of News Syndication

Stuart Maconie has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

First published by Ebury Press in 2015

www.eburypublishing.co.uk

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9780091933814

PROLOGUE

CLOCKING OFF

The train now leaving Stalybridge station is for the north

They call it Stalyvegas. A good place to start I think. A town that just wants to have fun.

But where to start with Stalybridge itself? With its long, dark, wild hills and its long, dark, wild history? It has plenty of that. Luddites, those mocked and misunderstood symbols of industrial muscle, once raged through its streets, smashing looms, burning mills, generally earning themselves centuries of undeserved bad press. Chartists made it a stronghold, collected signatures, stoked the peoples ire; strikers and plug rioters stalked the town, anger spread like a bloodstain across Lancashire, Yorkshire, Derbyshire, Staffordshire. Friedrich Engels came and found a town in disarray and a people in despair, despite some really rather lovely countryside.

Stalybridge lies in a narrow, crooked ravine and both sides of this ravine are occupied by an irregular group of cottages, houses and mills. On entering, the very first cottages are narrow, smoke-begrimed, old and ruinous; and as the first houses, so the whole town. A few streets lie in the narrow valley bottom, most of them run criss-cross, pell-mell, up hill and down, and in nearly all the houses, by reason of this sloping situation, the ground-floor is half-buried in the earth; and what multitudes of courts, back lanes and remote nooks arise out of this confused way of building may be seen from the hills, whence one has the town, here and there, in a birds-eye view almost at ones feet. Add to this the shocking filth, and the repulsive effect of Stalybridge may be readily imagined.

Understandably, the tourist board doesnt go big on the above in the promotional literature.

Or shall we begin with a chorus of Its a Long Way to Tipperary, written, its said, in an hour for a bet one boozy night in 1912 in Stalybridges Newmarket Tavern by local lad Jack Judge? Then theres another claim to fame, the fact that the last surviving tripe shop in Britain is still about its rubbery, vinegary business on Stalybridges Main Street. It is still a place of local pilgrimage, if only selling around a quarter of the mind-boggling, jaw-dropping, some would say stomach-turning 100lbs-a-day of the stuff they would sell 20 years ago.

Or shall we begin with that nickname; Stalyvegas, the city of lights in the wilderness, first used jokingly when the council went overboard on traffic lights and then used more abstractly and affectionately of a crazy, fun town in the middle of nowhere. An isolated town cradled by soft hills, turning rural again, feral even, as industrys tide recedes and the tripe trade slackens to be replaced by other passions; cocktail bars and bookies, tanning salons, Wetherspoons and pound shops.

But no. Let us begin on platform one of Stalybridge station where the trains clank and whizz and rumble their way between Lancashire and Yorkshire, and where stands what just might be the best pub in the north of England.

Youll need a drink after your journey. The northern rail train will be cramped and fetid, because it always is, packed sardine tight with the workers of Liverpool and Manchester and Bolton heading home to the hills; smart office girls in charcoal suits with pink paperbacks, hipster web designers with iPods and waxed tashes, exhausted labourers in blue serge overalls flecked with plaster nodding off against the rainy window, through which the landscape is gradually greening.

You wont get a seat, rest assured, so as the decrepit seventies Sprinter train sighs into Stalybridge you will fall gratefully out of the grimy concertina doors and onto platform 1, where the much more welcoming door of the Stalybridge Buffet Bar will be open, and the little lights will be twinkling and your stool or your table and your pint and the night await you.

The evening has begun.

A long, long time ago, an unimaginably long time actually somewhere between half a million and two million years our distant ancestor Homo erectus made the most important discovery of his or her short, action-packed life.

No one can be sure when or how it happened. A stray, fugitive spark from the sharpening of a flint axe head perhaps; or a lightning strike in a primeval forest bringing a crackle of sudden heat and light and a plume of smoke in the depths of a stormy Pleistocene night. But whatever it took, whatever happened, at some unknowable but undeniable point in the earths history, human beings discovered fire and how to control it.

Well never know when that was; certainly before 230,000 BC when we have evidence of hearths in Terra Amata, southern France. But whenever it occurred, this step, according to many modern anthropologists, marked the real beginnings of our culture. Firstly, of course, it meant a giant culinary leap for mankind. But it gets more interesting than that. Raw food is harder to digest and far less calorific than cooked; gorillas and other big primates have to spend eight hours a day eating to get enough calories to feed their small brains. When we invented cooking, we beefed up our brains far more speedily and easily than before, without having to spend the day sitting around gormlessly munching and masticating. Cooking made us smarter.