PENGUIN MODERN CLASSICS

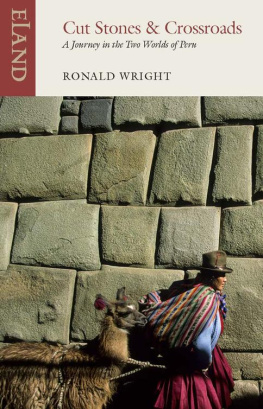

Cut Stones and Crossroads

RONALD WRIGHT is the author of ten books of history, fiction, and essays published in sixteen languages and in more than forty countries.

A Short History of Progress, from his 2004 CBC Massey Lectures, won the Libris Award for Non-Fiction Book of the Year and inspired Martin Scorseses 2011 documentary film Surviving Progress.

Wrights first novel, the dystopia A Scientific Romance, won Britains David Higham Prize for Fiction and was chosen as a book of the year by The New York Times, The Globe and Mail, and The Sunday Times. His other bestsellers include Time Among the Maya, What Is America?, and Stolen Continents, a history of the Americas since Columbus, which won the Gordon Montador Award and was chosen book of the year by The Independent and The Sunday Times. His latest work is the novel The Gold Eaters.

Wright contributes criticism to The Times Literary Supplement and other publications. He has also written and presented documentaries for radio and television on both sides of the Atlantic.

Born in England to Canadian and British parents, Wright read archaeology and anthropology at Cambridge University and has been awarded two honorary doctorates. He lives on Canadas West Coast. Visit his website at ronaldwright.com.

Born in Buenos Aires, ALBERTO MANGUEL is the internationally acclaimed, award-winning Canadian author of The Dictionary of Imaginary Places (co-written with Gianni Guadalupi), A History of Reading, The Library at Night, Curiosity, and All Men Are Liars, and the translator and editor of many other works.

Books by Ronald Wright

FICTION

The Gold Eaters

A Scientific Romance

Hendersons Spear

NON-FICTION

A Short History of Progress

On Fiji Islands

Time Among the Maya

Home and Away

Cut Stones and Crossroads

Stolen Continents

What Is America?

RONALD WRIGHT

Cut Stones and Crossroads

A JOURNEY IN THE TWO WORLDS OF PERU

With an Introduction by Alberto Manguel

Taytamamayman

To my parents

Contents

Introduction

by Alberto Manguel

From time to time, God causes men to be bornand thou art one of themwho have a lust to go abroad at the risk of their lives and discover newsto-day it may be of far-off things, tomorrow of some hidden mountain.

Rudyard Kipling, Kim

The great twelfth-century traveler Ibn al-Arabi defined the very origin of our human existence as movement. Immobility can have no part in it, wrote Ibn al-Arabi, for if existence were immobile it would return to its source, which is the Void. That is why the voyaging never stops, in this world or in the hereafter. With a malicious linguistic twist, Ibn al-Arabi confuses our endless movement through time, from cradle to grave, with a pragmatic movement through space. Certainly, even cloistered in ones room for the whole of ones life, one is condemned to travel through the years, hour after hour, each one wounding us, as a sundial motto has it, until the last one kills us. And yet, an opponent of Ibn al-Arabi might have argued movement from one point of this earth to another is merely a succession of moments of being still: our geography exists only in the instant in which we are there, standing on our own two feet.

This notion of travel as moving through space, but also being in one place at a time, is vividly exemplified in the travel books of Ronald Wright, Cut Stones and Crossroads and Time Among the Maya, and in the history told in Stolen Continents. For several decades now, he has diligently chronicled the ancient civilizations of Latin America, traveling through Peru and Mexico, and rooting himself in a succession of historical moments, visiting not only the present landscapes but also those long vanished, like the courageous Time Traveller imagined by H.G. Wells. Wright witnesses the past from the vantage point of the present and reports back to us.

Because of this ability to see what once was in the context of what now remains, his books translate his observations into essays that artfully combine travelogues with archaeological research, and political science with anthropology. The strategies of political power in our time and the weight of a fading tradition, the social memory of past events and the construction of the idea of history, the confused or lost identity of a conquered people and the identities imposed by the conquerorall these themes weave through Wrights books forming complex and illuminating patterns that allow the reader to share and begin to understand the crossroads to the past.

Wrights writing is not limited to essays; he is also the author of remarkable works of fiction. Aware that, to a degree, the material evidence of his travels curtails the scope of an explorers curiosity, Wright decided, a few years after publishing his travel books, to expand his wanderings into the realm of the imaginary. The result was two splendid novels of adventure: first, the prescient and terrifying A Scientific Romance and then Hendersons Spear with its parallel universes of sea travel and exploration. A Scientific Romance imagines a Britain turned tropical jungle in the climate changes of the not-too-distant future; Hendersons Spear conjures up the tale of a South Sea voyage undertaken during the Victorian age. Both are also travel books, and the fact that they never took place in reality does not disqualify them from being authentic.

Authenticity is the essential quality of all travel literature, imaginary or real. The vocabularies of the culture that formed us can distort or make us see a reality that is not that of the land extending before us, unless we place ourselves not in the position of someone who knows the answers but someone who is interested in the questions. Robert Frosts dictum that the land was ours before we were the lands is lethal to the observant traveler. Authenticity implies giving oneself over to the thing observed.

And yet, there is a paradox in the art of travel that seems impossible to overcome in order to achieve this required authenticity: that every discovery always entails some measure of recognition. Even as we set out, with unprejudiced eyes, to explore places where we have never been before, we are still incapable of seeing something entirely new if it were to appear suddenly before our eyes. We are all to a certain degree like Christopher Columbus who, during his third voyage to the New World, saw three manatees swimming near the mouth of the Orinoco River and jotted down in his journal, written in the third person, that today the Admiral saw three mermaids. (His honesty compelled him to add, But they are not as beautiful as they are supposed to be.) Fortunately, it is not how Ronald Wright has traveled.

When Cut Stones and Crossroads appeared in 1984, it was immediately hailed as a new kind of travel book, made up of personal anecdotes, erudite observations, fragments of conversations, and historical notes. The subtitle, A Journey in the Two Worlds of Peru, prepares the reader for the observation of a schizophrenic culture, half steeped in its Inca past, half suffering from the onslaught of the world of our century. The guide on this journey is an affable, intelligent, humorous Canadian (Wright was born in England) with a profound feeling for the complexities of the land of Peru, an aesthetic and historical appreciation of the ancient culture of the Incas, and a deep respect for the survivors of what was once one of the greatest empires in the history of the world.

Next page

![Harry Turtledove - Worlds that werent : [novellas of alternate history]](/uploads/posts/book/79050/thumbs/harry-turtledove-worlds-that-weren-t-novellas.jpg)