VINTAGE CANADA EDITION , 1998

Copyright 1996 by Alberto Manguel

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions.

Published in Canada by Vintage Canada,

a division of Random House of Canada Limited, in 1998.

First published in hardcover in Canada by Alfred A. Knopf Canada, Toronto, in 1996.

Distributed by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Vintage Canada and colophon are registered trademarks of

Random House of Canada Limited.

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace ownership of copyright materials.

Information enabling the Publisher to rectify any reference or credit in future editions will be welcomed.

Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data

Manguel, Alberto, 1948

A history of reading

eISBN: 978-0-307-36419-7

1. Books and reading History. 2. Reading History. I. Title.

Z1003.M35 1997 028.09 C96-930984-8

Visit Random House of Canada Limiteds Web site: www.randomhouse.ca

v3.1

TO CRAIG STEPHENSON ,

That day she put our heads together,

Fate had her imagination about her,

My head so much concerned with outer

Yours with inner weather.

After Robert Frost

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Over the seven years that this book was in the making,

Ive accumulated a fair number of debts of gratitude. The notion of writing a history of reading began with an attempt to write an essay; Catherine Yolles suggested that the subject deserved a whole book my gratitude to her for her confidence.

Thanks to my editors Louise Dennys, most gracious of readers, whose friendship has supported me since the faraway days of The Dictionary of Imaginary Places; Nan Graham, who stood by the book at the very beginning, and Courtney Hodell, whose enthusiasm accompanied it to the end; Philip Gwyn Jones, whose encouragement helped me read on through difficult passages.

Painstakingly and with Sherlockian skill, Gena Gorrell and Beverley Beetham Endersby copyedited my manuscript: to them my thanks, as usual. Paul Hodgson designed the book with intelligent care. My agents Jennifer Barclay and Bruce Westwood kept wolves, bank managers and tax collectors from my door.

A number of friends made kind suggestions Marina Warner, Giovanna Franci, Dee Fagin, Ana Becci, Greg Gatenby,

Carmen Criado, Stan Persky, Simone Vauthier. Professor Amos Luzzatto, Professor Roch Lecours, M. Hubert Meyer and Fr. F.A. Black generously agreed to read and correct a few individual chapters; the errors remaining are all my own. Sybel Ayse Tuzlac did some of the early research. My heartfelt thanks to the library staff who dug out odd books for me and patiently answered my unacademic questions at the Metro Toronto Reference Library, Robarts Library, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library all in Toronto Bob Foley and the staff of the library at the Banff Centre for the Arts, the Bibliothque Humaniste in Slestat, the Bibliothque Nationale in Paris, the Bibliothque Historique de la Ville de Paris, the American Library in Paris, the Bibliothque de lUniversit de Strasbourg, the Bibliothque Municipale in Colmar, the Huntington Library in Pasadena, California, the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan, the London Library and the Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana in Venice. I also wish to thank the Maclean Hunter Arts Journalism Programme and the Banff Centre for the Arts, and Pages Bookstore in Calgary, where parts of this book were first read.

It would have been impossible for me to complete this book without financial assistance from the pre-Harris Ontario Arts Council, and the Canada Council, as well as from the George Woodcock fund.

In memoriam Jonathan Warner, whose support and advice I very much miss.

TO THE READER

Reading has a history.

ROBERT DARNTON

The Kiss of Lamourette, 1990

For the desire to read, like all the other desires which distract our unhappy souls, is capable of analysis.

VIRGINIA WOOLF

Sir Thomas Browne, 1923

But who shall be the master? The writer or the reader?

DENIS DIDEROT

Jaques le Fataliste et son matre, 1796

CONTENTS

THE LAST

PAGE

Read in order to live.

G USTAVE F LAUBERT

Letter to Mlle de Chantepie, June 1857

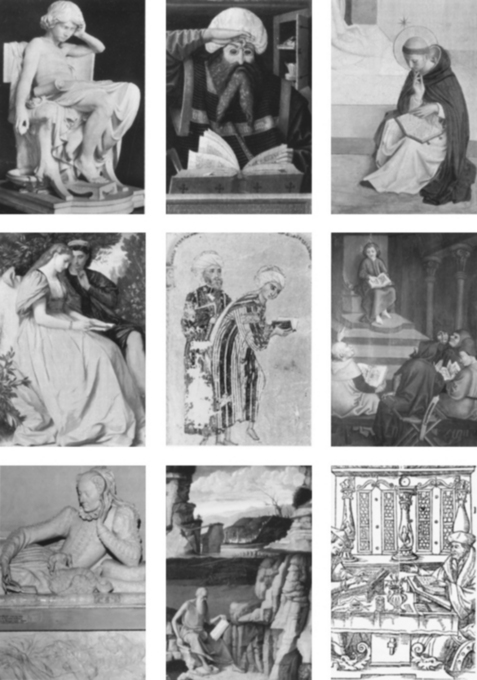

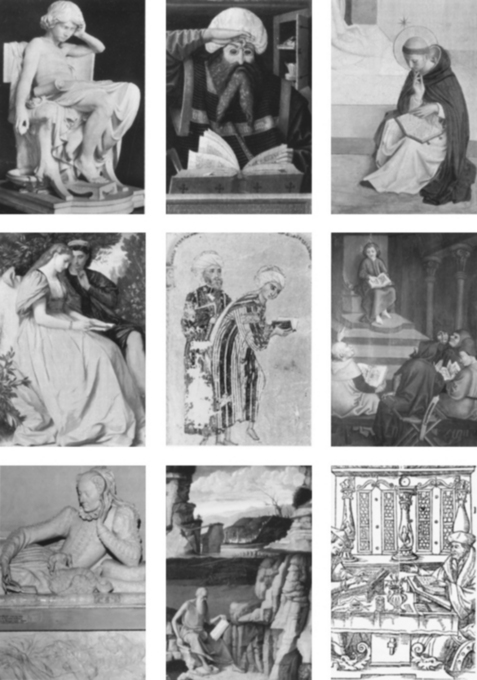

A universal fellowship of readers. From left to right, top to bottom: the young Aristotle by Charles Degeorge, Virgil by Ludger tom Ring the Elder, Saint Dominic by Fra Angelico, Paolo and Francesca by Anselm Feuerbach, two Islamic students by an anonymous illustrator, the Child Jesus lecturing in the Temple by disciples of Martin Schongauer, the tomb of Valentine Balbiani by Germain Pilon, Saint Jerome by a follower of Giovanni Bellini, Erasmus in his study by an unknown engraver.

THE LAST PAGE

ne hand limp by his side, the other to his brow, the young Aristotle languidly reads a scroll unfurled on his lap, sitting on a cushioned chair with his feet comfortably crossed. Holding a pair of clip glasses over his bony nose, a turbaned and bearded Virgil turns the pages of a rubricated volume in a portrait painted fifteen centuries after the poets death. Resting on a wide step, his right hand gently holding his chin, Saint Dominic is absorbed in the book he holds unclasped on his knees, deaf to the world. Two lovers, Paolo and Francesca, are huddled under a tree, reading a line of verse that will lead them to their doom: Paolo, like Saint Dominic, is touching his chin with his hand; Francesca is holding the book open, marking with two fingers a page that will never be reached. On their way to medical school, two Islamic students from the twelfth century stop to consult a passage in one of the books they are carrying. Pointing to the right-hand page of a book open on his lap, the Child Jesus explains his reading to the elders in the Temple while they, astonished and unconvinced, vainly turn the pages of their respective tomes in search of a refutation.

ne hand limp by his side, the other to his brow, the young Aristotle languidly reads a scroll unfurled on his lap, sitting on a cushioned chair with his feet comfortably crossed. Holding a pair of clip glasses over his bony nose, a turbaned and bearded Virgil turns the pages of a rubricated volume in a portrait painted fifteen centuries after the poets death. Resting on a wide step, his right hand gently holding his chin, Saint Dominic is absorbed in the book he holds unclasped on his knees, deaf to the world. Two lovers, Paolo and Francesca, are huddled under a tree, reading a line of verse that will lead them to their doom: Paolo, like Saint Dominic, is touching his chin with his hand; Francesca is holding the book open, marking with two fingers a page that will never be reached. On their way to medical school, two Islamic students from the twelfth century stop to consult a passage in one of the books they are carrying. Pointing to the right-hand page of a book open on his lap, the Child Jesus explains his reading to the elders in the Temple while they, astonished and unconvinced, vainly turn the pages of their respective tomes in search of a refutation.

Beautiful as when she was alive, watched by an attentive lap-dog, the Milanese noblewoman Valentina Balbiani flips through the pages of her marble book on the lid of a tomb that carries, in bas-relief, the image of her emaciated body. Far from the busy city, amid sand and parched rocks, Saint Jerome, like an elderly commuter awaiting a train, reads a tabloid-sized manuscript while, in a corner, a lion lies listening. The great humanist scholar Desiderius Erasmus shares with his friend Gilbert Cousin a joke in the book he is reading, held open on the lectern in front of him. Kneeling among oleander blossoms, a seventeenth-century Indian poet strokes his beard as he reflects on the verses hes just read out loud to himself to catch their full flavour, clasping the preciously bound book in his left hand. Standing next to a long row of roughly hewn shelves, a Korean monk pulls out one of the eighty thousand wooden tablets of the seven-centuries-old

ne hand limp by his side, the other to his brow, the young Aristotle languidly reads a scroll unfurled on his lap, sitting on a cushioned chair with his feet comfortably crossed. Holding a pair of clip glasses over his bony nose, a turbaned and bearded Virgil turns the pages of a rubricated volume in a portrait painted fifteen centuries after the poets death. Resting on a wide step, his right hand gently holding his chin, Saint Dominic is absorbed in the book he holds unclasped on his knees, deaf to the world. Two lovers, Paolo and Francesca, are huddled under a tree, reading a line of verse that will lead them to their doom: Paolo, like Saint Dominic, is touching his chin with his hand; Francesca is holding the book open, marking with two fingers a page that will never be reached. On their way to medical school, two Islamic students from the twelfth century stop to consult a passage in one of the books they are carrying. Pointing to the right-hand page of a book open on his lap, the Child Jesus explains his reading to the elders in the Temple while they, astonished and unconvinced, vainly turn the pages of their respective tomes in search of a refutation.

ne hand limp by his side, the other to his brow, the young Aristotle languidly reads a scroll unfurled on his lap, sitting on a cushioned chair with his feet comfortably crossed. Holding a pair of clip glasses over his bony nose, a turbaned and bearded Virgil turns the pages of a rubricated volume in a portrait painted fifteen centuries after the poets death. Resting on a wide step, his right hand gently holding his chin, Saint Dominic is absorbed in the book he holds unclasped on his knees, deaf to the world. Two lovers, Paolo and Francesca, are huddled under a tree, reading a line of verse that will lead them to their doom: Paolo, like Saint Dominic, is touching his chin with his hand; Francesca is holding the book open, marking with two fingers a page that will never be reached. On their way to medical school, two Islamic students from the twelfth century stop to consult a passage in one of the books they are carrying. Pointing to the right-hand page of a book open on his lap, the Child Jesus explains his reading to the elders in the Temple while they, astonished and unconvinced, vainly turn the pages of their respective tomes in search of a refutation.