The Traveler, the Tower, and the Worm

MATERIAL TEXTS

Series Editors

Roger Chartier

Leah Price

Joseph Farrell

Peter Stallybrass

Anthony Grafton

Michael F. Suarez, S.J.

A complete list of books in the series is available from the publisher.

ALBERTO MANGUEL

The TRAVELER, the TOWER, and the WORM

The Reader as Metaphor

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA PRESS

PHILADELPHIA

Copyright 2013 Alberto Manguel

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 191044112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Manguel, Alberto.

The traveler, the tower, and the worm : the reader as metaphor / Alberto Manguel.

1st ed.

p. cm. (Material texts)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN: 9780-81224523-3 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Literature and anthropology. 2. Literature and society.

3. Signs and symbols. 4. Books and readingPhilosophy.

GN452.5.M36 2013 2013005806

809.3 dc23

For Craig, with all my love

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

There are no such things as facts, only interpretation.

Friedrich Nietzsche, Posthumous Papers

As far as we can tell, we are the only species for whom the world seems to be made of stories. Biologically developed to be conscious of our existence, we treat our perceived identities and the identity of the world around us as if they required a literate decipherment, as if everything in the universe were represented in a code that we are supposed to learn and understand. Human societies are based on this assumption: that we are, up to a point, capable of understanding the world in which we live.

To understand the world, or to try and understand it, translation of experience into language is not enough. Language barely glances the surface of our experience, and transmits from one person to another, in a supposedly shared conventional code, imperfect and ambiguous notations that rely both on the careful intelligence of the one who speaks or writes and on the creative intelligence of the one who listens or reads. To enhance the possibilities of mutual understanding and to create a larger space of meaning, language resorts to metaphors that are, ultimately, a confession of languages failure to communicate directly. Through metaphors, experiences in one field become illuminated by experiences in another.

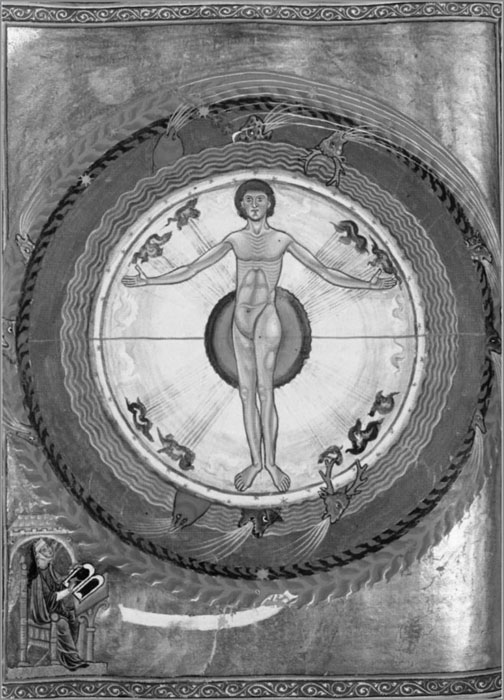

Hildegard von Bingen, Cosmic Man.

From Liber divinorum operum (c. 11701174).

Aristotle suggested that the power of a metaphor resides in the recognition conjured up in the audience; that is to say, the audience must invest the subject of the metaphor with a particular shared meaning. Literate societies, societies based on the written word, have developed a central metaphor to name the perceived relationship between human beings and their universe: the world as a book that we are meant to read. The ways in which this reading is conducted are manythrough fiction, mathematics, cartography, biology, geology, poetry, theology, and myriad other formsbut their basic assumption is the same: that the universe is a coherent system of signs governed by specific laws, and that those signs have a meaning, even if that meaning lies beyond our grasp. And that in order to glimpse that meaning, we try to read the book of the world.

Not every literate society assumes this central image in the same way, and the different vocabularies that we have developed to name the act of reading reflect, at specific times and in specific places, the ways in which a certain society defines its own identity. Cicero, contesting Aristotles assumptions, warned against the idle use of metaphors merely for adornments sake. In On Oratory, he wrote that just as clothes were in the beginning invented to protect us against the cold and later began to be worn as adornment and dignity, the use of metaphors started because of poverty but became of common use for the sake of entertainment. For Cicero, metaphors are born from the poverty of language, that is to say, from the inability of words to name our experience exactly and concretely. To use metaphors in a merely decorative function is to debase their essential enriching power.

Out of a basic identifying metaphor society develops a chain of metaphors. The world as book links to life as a voyage, and so the reader is seen as a traveler, advancing through the pages of that book. Sometimes, however, on that journey the traveler does not engage with the landscape and its inhabitants but proceeds, as it were, from sanctuary to sanctuary; the activity of reading is then confined to a space in which the traveler withdraws from the world instead of living in the world. The biblical metaphor of the tower denoting purity and virginity, applied to the Bride in the Song of Songs and to the Virgin Mary in medieval iconography, becomes transformed centuries later into the ivory tower of the reader, with its negative connotations of inaction and disinterest in social matters, the opposite of the reader-traveler. The traveler metaphor evolves and the textual pilgrim becomes in the end, like all mortal beings, prey of the Worm of Death, a grandiose image of that other, more modest pest that gnaws through the pages of books, devouring paper and ink. The metaphor folds back upon itself, and just as the Worm devours the reader-traveler, the reader-traveler (sometimes) devours books, not to benefit from the learning they contain (and life displays) but merely to become bloated with words, reflecting back the work of Death. Thus the reader is derided for being a worm, a mouse, a rat, a creature for whom books (and life) are not nourishment but fodder.

These metaphors are not always explicitly set out. Sometimes the idea presents itself, implicit in its context, but the metaphor that will illuminate it has itself not yet been named. In fact, in some cases, as in that of the ivory tower, the metaphor is created long after the idea has been present in society. It is difficult, except in a few cases, to track the appearance of the metaphors themselves; perhaps more useful, more revealing, is to discuss certain instances of the presence and development of the notion behind the metaphor. In one of my early books, A History of Reading, I dedicated several pages to explore the metaphors related to our craft. I attempted to trace some of the most common ones but felt that the subject merited a more in-depth exploration; the result of that insatisfaction is the present book.