MAIMONIDES

Maimonides

Faith in Reason

ALBERTO MANGUEL

Jewish Lives is a registered trademark of the Leon D. Black Foundation.

Copyright 2023 by Alberto Manguel

c/o Schavelzon Graham Agencia Literaria, S.L.

www.schavelzongraham.com

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in Janson Oldstyle type by Integrated Publishing Solutions.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022937726

ISBN 978-0-300-21789-6 (hardcover : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992

(Permanence of Paper).

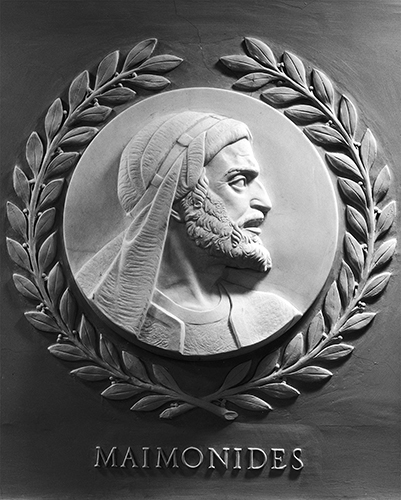

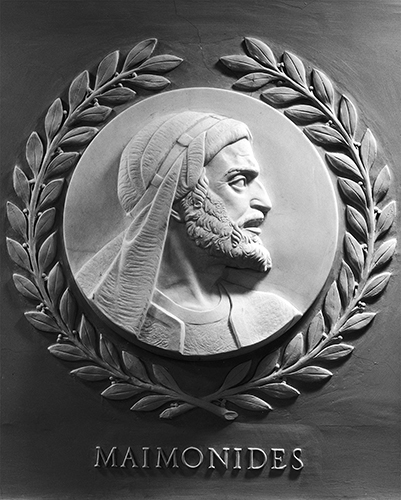

: Brenda Putnam, Marble bas-relief of Maimonides, 1950.

This is one of twenty-three reliefs of great historical lawgivers in the

chamber of the U.S. House of Representatives in the United States Capitol. (Photo: Architect of the Capitol/Wikimedia Commons)

ALSO BY ALBERTO MANGUEL

Nonfiction

Fabulous Monsters: Dracula, Alice, Superman, and Other Literary Friends

Packing My Library: An Elegy and Ten Digressions

Curiosity

The Traveler, the Tower and the Worm: The Reader as Metaphor

A Reader on Reading

The Library at Night

A Reading Diary

With Borges

Reading Pictures

A History of Reading

The Dictionary of Imaginary Places (with Gianni Guadalupi)

Fiction

All Men Are Liars

Stevenson Under the Palm Trees

News From a Foreign Country Came

To my father, Pablo Manguel

... a cry issued from his fathers lips:

Have you come at last?

And has the fealty your father expected

overcome the harsh road?

Aeneid 6.708709

CONTENTS

PREFACE

Remember the days of old, consider the years of many generations: ask thy father, and he will shew thee; thy elders, and they will tell thee.

Deuteronomy 32:7

EARLY IN 2015, my editor at Yale University Press suggested that I write one of the volumes for the Jewish Lives series she was directing, on Moses Maimonides. I had a vague notion of who Maimonides was (a great philosopher, a great legislator, a great medical doctor), and I remembered the intriguing title of his Guide of the Perplexed, but little more. I thought that Maimonides might be suitable to my condition of permanent perplexity.

That same year I had left my house in France, packed up my library, and sent the boxes of books to be stored at the warehouse of my Quebec publisher in Montreal. I accepted a couple of teaching positions in New York (a city in which I had never lived) and settled in the small apartment of a professor on sabbatical. I began to plan my reading of Maimonides. I filled in a readers card at the Center for Jewish History in Manhattan, I sifted through the shelves of Judaica at the Strand Bookstore, I got permission to take out books at the Columbia University Library. I started to read several biographies of Maimonides, histories of al-Andalus, North Africa, and Egypt, books on Arab philosophy, books on the Talmud and Jewish law, histories of medieval medicine. The more I read, the vaster my subject became.

I come from a Jewish family, but I had no idea I was Jewish until I was eight, after an anti-Semitic incident for which the bewildering accusation from a bullying classmateYour father likes money, doesnt he?had to be explained to me. A very old great-uncle, the brother of my fathers mother, gave me some lessons to prepare me for my bar mitzvah, and I learned by heart a few words which I mumbled in the synagogue on my thirteenth birthday. I still remember the words Baruch atah Adonai, Elohenu melech haolam, which, I discovered many decades later, were the first words of the Shehecheyanu, the Jewish prayer of thanks. If I still knew the prayer by heart, I would gratefully recite it several times a day.

Maimonides was educated in a society in which several cultures were in constant though sometimes acrimonious dialogue. The Islamic, Jewish, and to a lesser extent Christian communities interacted with and learned from one another. And even when religious politics forced Maimonides into exile from al-Andalus (his beloved Sepharad) to North Africa, from there to Christian Palestine, and finally to Egypt, he never stopped learning from the cultures he encountered in the fields of religion, philosophy, and medical science. He was a very practical man: he took up medicine as a profession once the family business failed (like Socrates, he thought it was unethical for a teacher to charge for his teaching), and in his Epistle on Conversion (also called Epistle on Martyrdom or Letter on Apostasy), or Iggeret ha-Shemad, he excused those who converted to save their lives, saying that God required us to live, not die, for our faith.

Every Jew, from the days of Exodus on, is to some degree a wanderer, and though the story of the Eternal Wanderer is, for writers as different as Homer, Dante, Cames, and Joyce, emblematic of all human life, for a Jew the legend is contaminated by the experience of persecution and suffering born of an ancestral and irrational hatred toward the inventors of monotheism. But not all wandering is due to persecution. In my case, it certainly was not, and the many places in which I have lived have never seemed to me enforced habitations. Rather, they have been, for a variety of reasons, the result of conscious choices. However, after reading about Maimonides peregrinations, I identified with the experience of constantly changing landscapes, voices, customs, languages, and skies. I often wondered how these metamorphoses were affecting meto what extent a change of vocabulary, of conventions of tone and style transformed my way of thinking and interpreting. I discovered that for Maimonides these changes enriched his own thoughts through contact with, for instance, the science of astronomy in Seville (possibly), Islamic legal systems in Morocco, Christian politics in Palestine, Arab medicine in Egypt. But his bedside books remained the same: the Torah, with its 613 commandments of Jewish Law, and the two Talmuds, the Jerusalem and the Babylonian. What kept changing was his dialogue with those texts through his newly acquired knowledge, enriching both his reading and his commentaries on his reading. After following Maimonides, I became more conscious of how the different experiences of place had changed me and my relationship to my books.

Someone who has not experienced transience, whether as a voluntary traveler or an enforced exile, someone rooted in one place from cradle to grave, eating nothing that has not grown within the narrow circle around his or her birthplace (as the Romans enjoined), someone who cares for nothing that is not endemic (as nationalists and Dickenss Mr. Podsnap do) must possess a wonderful single-mindedness of spirit and a stringency of purpose that would hardly allow for digressive inquiry and healthy curiosity. After reading Maimonides, I saw reflected in his writings my own mania for putting things in physical order (as in his

Next page