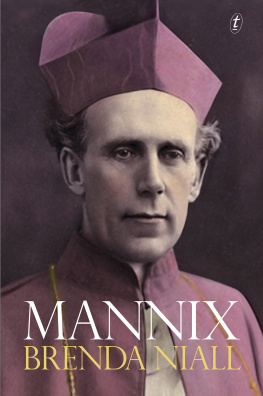

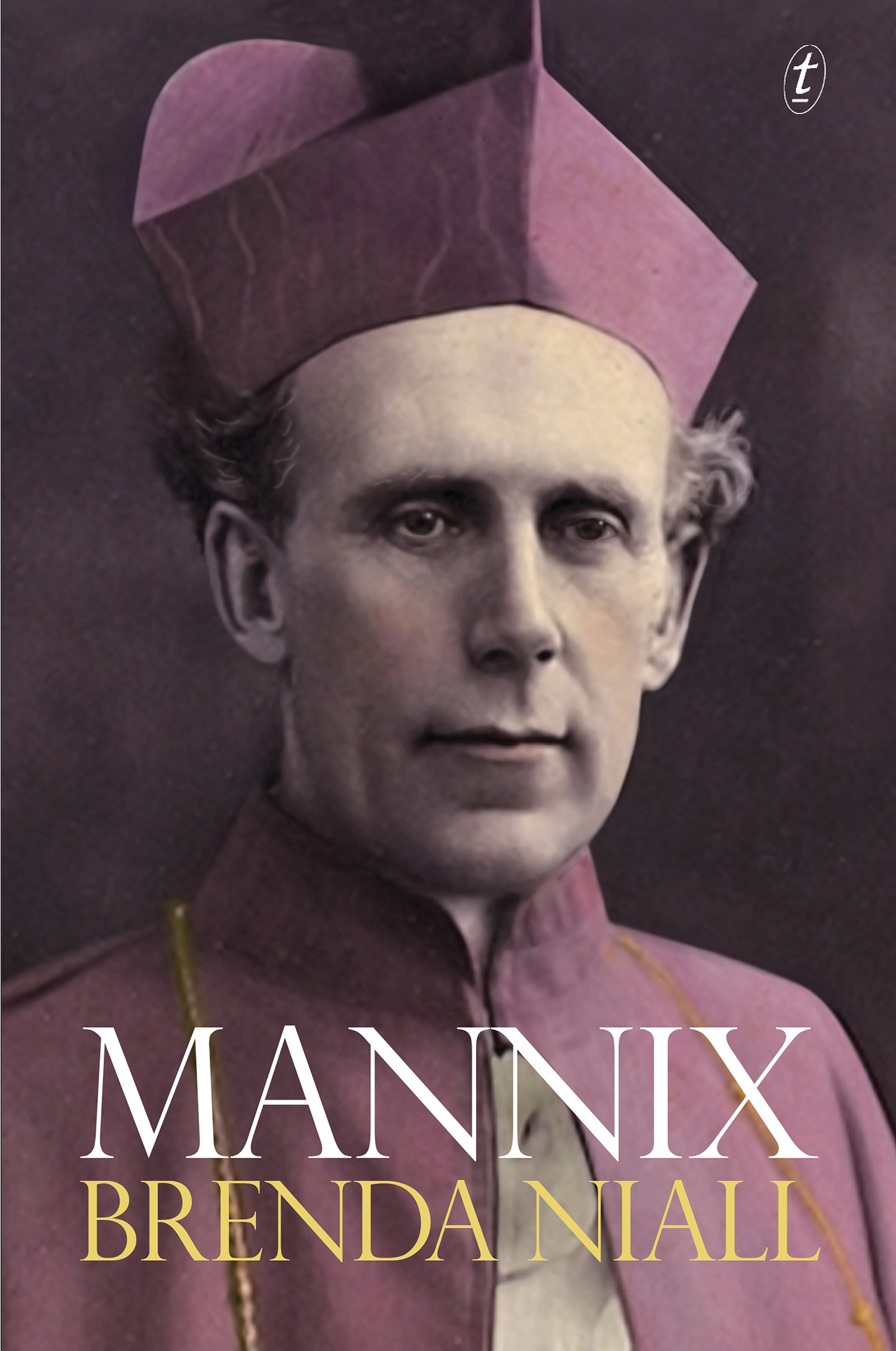

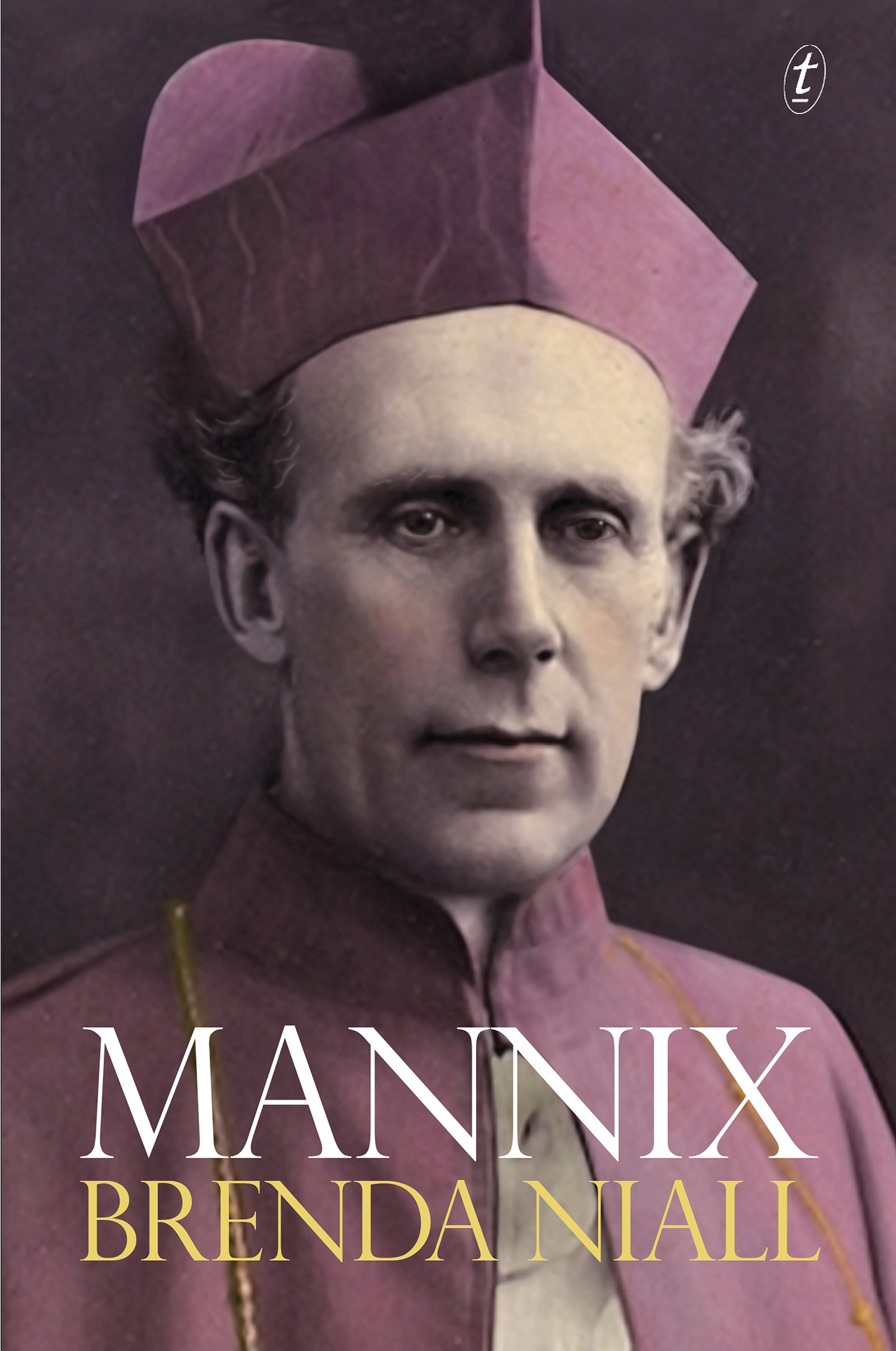

BIOGRAPHERS BEGIN with facts and opinions, find enlightenment along the way if werelucky, and end with questions. We would delude ourselves if we thought the full truthcould ever be found, or that any volume would be big enough to contain it. I keepin mind Henry Jamess warning: Never say you know the truth about any human heart.I remember too that Mannix was so wary of biographers that he ordered the destructionof his private papers. Total destruction, of course, wasnt possible; his decisiononly made his biographers work harder. He made it more likely, too, that he wouldbe misunderstood, even caricatured, as he has often been in popular accounts.

There have been eight biographies of Mannix. I have learned from them all, as I havelearned from a huge mass of commentary in various forms. What today seems an excessof idealisation was taken for granted in an earlier period. Idealisation and aggression are two sides of the same coin. Pope Francis has protested against being depictedas a sort of Superman, a star. For his own people, or many of them, Mannix was astar. His opponents demonised him. In the triumphalist church of his time it washard for him to be, in Pope Franciss terms, a man who laughs, cries, sleeps calmlyand has friends like anyone else.

Some questions that seem obvious to me in 2015 would not have occurred to a biographerin the 1960s or the 1980s, not because I can claim to be more perceptive but becausethe world has changed, and will keep changing. This wont be the last word on DanielMannix.

For me, one of the most interesting decades in Mannixs life is the final one, whenhe was looking back at all that he had done and not done. He was listening then toyoung men who brought their perplexities to Raheen, and he was forming the viewsthat emerged in the remarkable document he sent to the Second Vatican Council. Ithink of the old man in the green dressing-gown, confined to his room but travellingwidely in thought and memory. When Mannix gave orders in 1958 for a simple funeral,no procession and no panegyric, was he remembering that distant day in 1917 whenhe walked behind Archbishop Carrs coffin and felt the peoples love for that fatherlyfigure? His wish for a simple, even humble, farewell matches his later reflectionsfor the Vatican Council on the hardness, even pride that he disliked in the DeEcclesia statement. He was casting his final vote against the clericalism that hasproved so destructive.

I dont think that Daniel Mannix can be seen in gloom or in rosy glow. More thanmost, he is a man for light and shade. We dont have to choose a single focus orlook for consistency: that would deprive Mannix of all that made him human. He wasa man for the big occasion; he took the spotlight with apparent ease. Interviews,portraits, photographs, sketches and cartoons exposed him to the world. Yet he livedas a recluse. In his top hat and frock coat and his indifference to the telephoneand the motor car, he presented himself as a man of the past but his thinking wasadvanced enough, in 1938, to insist on the need to make reparation to the Aborigines.

There are records of hundreds of thousands of words spoken by the church leader andthe political interventionist, but the man who spent up to five hours each day inprayer left no spiritual journal or private diary.

He made it hard for biographers to find his private self but the patterns are thereto be discerned in the choices he made and the people and the causes that arousedhis sympathies.

Envelopes held in Mannix College Collection, Monash University.

William Hackett SJ has described the urgency with which Robert Barton preparedhis statement and the difficulty in getting it typed in Dublin. Knowing he was undersurveillance, he asked Hackett (who was sent to Australia in September 1922) to deliverit by hand to Mannix. Hackett Papers.

Michael Wallis to Jack Wallis, 20 August 1925. Mannix Papers.

The story of the burning was confirmed by Father T. P. Boland, biographer of ArchbishopDuhig, who questioned May Saunders. It took her three days to do it. Boland toBrenda Niall, February 2009.

Australian Archives Series A8911, nos. 236, 240.

Noted by Vera Orschel, Papers of John Hagan, Irish College Rome, Archival Catalogue,2008, p. vii.

Fr Morley Coyne, interview with the author, 1959.

Paul Duffy SJ helped Santamaria to pack the papers. Duffy, pers. comm., 2010.

: THE BIG HOUSE

Interview with Sr Carmela Cagney, Murtagh Papers.

An Advocate galley proof of the 1955 speech, corrected in Mannixs hand, strikesout the reference to peasantry. Parer Papers.

In the Irish Census of 1901 Ellen Mannix is the only family member listed as Irish-speaking.

T. P. Boland, Thomas Carr, p. 3.

Tim Pat Coogan, De Valera, p.10.

T. Ryle Dwyer, Big Fellow, Long Fellow, p. 248.

Mark Bence-Jones, Burkes Guide to Irish Country Houses, vol. 1, p. 82.

Dr Patrick Cagney, interview with James Murtagh, Murtagh Papers.

Paul Bew, Ireland: The Politics of Enmity, p. 264.

Rev Dr Croke to Thomas Sanders, 17 December 1868, quoted in Ebsworth, ArchbishopMannix, p. 34.

Irish Census 1901 and 1911.

Barry Coldrey, Faith and Fatherland, p. 92. Coldrey shows that Latin was beingtaught in some Christian Brothers schools in the 1860s, but that it was not at thattime a priority.

Walter A. Ebsworth, p. 28.

Transcribed by James Murtagh from English translation of Peadar OLaoghaire, MoScal Fin, My Own Story, chapter 23, Murtagh Papers.

University College, Cork, Records, courtesy Professor Dermot Keogh.

Colm Kiernan, Daniel Mannix and Ireland, p. 6.

Patricia Wallis-McCombe to Danny Cusack, 2013.

Sister Carmela Cagney, interview with James Murtagh, Murtagh Papers.

Cork Examiner, 4 January 1881, quoted in Kiernan, Daniel Mannix and Ireland, p.8.

Kiernan, Daniel Mannix and Ireland, pp. 89.

Published Dublin, Hodges Figgis, 1903.

Bob Mannix, grandson of Patrick Mannix, interview, Melbourne, 14 April 2013, andsubsequent correspondence.

: MAYNOOTH

I have drawn on T. P. Bolands description of Maynooth in Thomas Carr, pp. 1553and passim.

John Healy, Maynooth College, p. 455. (It is not clear whether the author is quotingMcHale or paraphrasing him.)

Figures (1552 women in convents in 1851 rose to 8031 in 1901) taken from IrishCensus, quoted by Margaret MacCurtain, Godly Burden: Catholic Sisterhoods in 20th-CenturyIreland, in Anthony Bradley and M. G. Valiulis (eds.), Gender and Sexuality in ModernIreland, p. 245.

Patrick J. Corish, Maynooth College 17951995, p. 238.

Ibid, p. 236.

Francis Hackett, The Green Lion, p. 234. Younger brother of Mannixs Jesuit friendWilliam Hackett, Francis Hackett was describing the Clongowes schoolboy intake, butthe sense of difference would apply at Maynooth too.

Healy, pp. 46667 and passim.

Corish, p. 229.

See Walter McDonald, Reminiscences of a Maynooth Professor, pp. 8182, re bringingin religious women to take charge in kitchen and refectory; this was resisted formany years while the use of untrained male servants had led to disorder and low standards.

Recalled by Dean Goidenich, quoted in Michael Gilchrist, Daniel Mannix: Wit andWisdom, p. 6.

Boland, Thomas Carr, p. 39.

Ibid, pp. 3738.

Ibid, p. 41.

Father Brian Quillinan CSSR, pers. comm., 2013.

Corish, p. 199.

F. S. L. Lyons, The Fall of Parnell, pp. 11617.

Ibid, p. 116.

Next page