Brenda Niall, arguably Australias foremost biographer, looks back on her own life and the circumstances, events and choices that shaped her career.

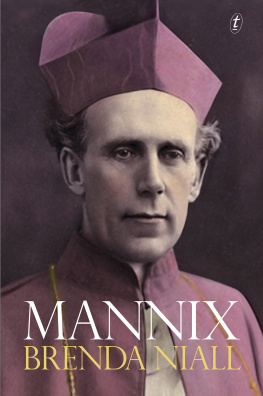

My Accidental Career spans nine decades, from her childhood in the Melbourne suburb of Kewwhere powerful neighbours included prime minister Menzies, millionaire gambler John Wren and Archbishop Daniel Mannixto her university days, her first job writing reviews for a magazine and her travels in Ireland after breaking off her engagement to a suitable young man. Its a lively account of academic life at the newly established Monash University in the 1960s, a time when women were rare in university departments and even more rarely promoted, the snakes and ladders ups and downs of her time in the US, and of her charting new territory in Australian biography with acclaimed works on artists, writers and leaders.

Brenda Nialls career isnt one of struggle against the odds in a mans world but one of quiet, confident work that couldnt be ignored. Her Jane Austen-like wit and elegant prose enlivens this story of Australian womens history seen through the lens of her remarkable life.

CONTENTS

When I applied for my first passport, in 1957, I didnt know what to put under Occupation in the questionnaire. Strictly speaking, I was unemployed. I had resigned from my job to be married, changed my mind, and was taking an overseas trip, mainly for pleasure, but also to think about my future. For most of my friends, the Occupation slot would have been easy to fill. Home Duties was what women did: the home was where we all belonged, and the off-putting word Duties wasnt questioned. In stepping aside from a suitable marriage, at the then advanced age of twenty-seven, Id lost my way on the well-trodden path to becoming a wife and mother. And in the 1950s, there werent many alternatives. Careers were for men: not many women expected to earn their own living, and if they did it was a slur on their husbands capacity to be his familys sole support.

My first job was a cul de sac, interesting enough, but leading nowhere. Although the idea of independence was alluring, it wasnt easily won in a period when women earned half the male rate, and were expected to resign on marriage from the public service and teaching jobs.

Looking back over more than sixty years of work as academic and writer, I see a pattern of surprises. For better and worse, fortunes wheel kept spinning. Am I right in thinking of an accidental career? Freud said there were no accidents, and its easy to look back and see inevitabilities in events that seemed random. In the following pages Ive tried to show how it felt at the time, when each turn of fate appeared to me as unpredictable. To be born in 1930 meant that I entered the adult world well before the sharp, fresh breeze of the womens movement. With my own inner wars of independence to fight, I had little awareness of the public world as a shaping force.

When, after a tentative push, the doors to a career had opened, I didnt have the sense of struggling in a mans world that younger women rightly felt. Somehow, in what I persist in seeing as a series of accidents in which timing played a big part, I found two satisfying careers. My Accidental Career is the story of a 1950s consciousness gradually waking up to a new world in which opportunity and equality were within a womans reach. And that I wanted them.

Every autobiographical work, every version of self, is shaped by the writers point of view at the time of writing. I write now at the age of ninety-one, astonished at having lived longer and written far more than I ever expected. My writing career is more fully present to me now than my years as an academic, which ended at the preordained time. Writers dont have to stop. After writing nine biographies, I can ponder the events and encounters that got me to this point. If I were to be asked my occupation now, I would know what to say.

Lets begin with an early studio portrait of the family. There I am at the centre, not yet two years old, my small plump fingers holding an alphabet block. No one in the group is interested in the camera. My mother, sister and brother are all looking down at me as I give absorbed attention to the painted letters, frowning a little as if determined to understand. The camera shows one letter: the X. Ive always liked that picture, not because I am the focus, but because my mother looks so pretty in a soft, pale-green chiffon dress that I remember as my favourite. Philippa, nearly six, is in white lace with a pink ribbon, and four-year-old John has a white shirt with blue smocking. How did they feel about the attention given to the little sister whose asthma so often disrupted the house? I used to watch longingly from the window as they played together while I was safely wrapped up inside. Looking at the picture now, I am surprised to see myself as round-cheeked, pink and healthy. Yet asthma, which dominated my life from the age of three months, meant a protected childhood from which I emerged slowly and at times fearfully.

The first memory that comes to mind is the gingerbread house that we made at kindergarten. I was three years old when my mother took me across the road to a big playroom in the Convent of the Sacred Heart in Burke Road, Glen Iris. Philippa and John were in grades three and two in the main school. The kindergarten teacher, Hilde Streich, a pretty young woman from Stuttgart, was trained in the Froebel method by which children learn by playing. Seated at a big table, we made cut-outs with blunt scissors from sheets of coloured paper and drew with bright crayons on white paper. We climbed on the rocking horse or bounced back and forth in a green rocker that held all six of our little group. Nearly everything was in miniature. Our chairs were as small as those in Alice in Wonderlands tea party. Hilde presided in her white uniform, her golden hair neatly braided and wound round her head. Her kindergarten was such a gentle introduction to school that it hardly counted. Apart from an ABC on the blackboard, there wasnt any instruction. I had learned to read at home, so the Big A and Little A didnt offer anything new. Hilde taught me to count to ten in German, and to recite a four-line poem that began Ich bin Klein.

One morning, when Christmas came close, an enormous snowman in white chalk, with a green hat, appeared on the blackboard. Hildes snowman evoked a northern landscape none of us had seen. The gingerbread house that she created was the magical embodiment of the folk and fairy stories my mother and grandmother read to me. I dont know where the gingerbread came from. Perhaps Hilde made it herself in the convent kitchens and brought it in so that we could see her do the decorating. We watched it take shape: green front door, with a tiny doorhandle in red sugar icing, windows on either side, iced in green, and a steep-sided snow-covered roof with a silver star perched on top. We all longed to touch it, but were held back by Hilde Streichs stern NOT YET.

For a short time, the gingerbread house was on a high shelf to be gazed at. Then, on the last day before the Christmas holidays, we were told that the house was to be taken down and that we could take a piece of gingerbread home. This was a difficult moment. I wanted my share of the gingerbread, but not at the cost of breaking up the house. I wept at the thought, but took my piece of gingerbread to eat to the last crumb. I was given the front door with its red and green icing which, apart from the roof of thickly spread royal icing that dripped like snow down the walls, was the most coveted piece. I dont think anyone got the whole roof; even half would have been more than enough for an under-five.