Moving beyond the rather tired liberal versus conservative dichotomy that characterises so much contemporary discussion of Menzies this work provides a rich contextual study not only of Menzies, but of generations of Australians whose worldview he reflected and helped shape.

Ian Tregenza, Macquarie University

The Forgotten Menzies is an important contribution to Australian intellectual history and a timely reminder that contemporary cultural appropriation of historical figures can belie the complexity of political thought and action.

Margaret Van Heekeren, University of Sydney

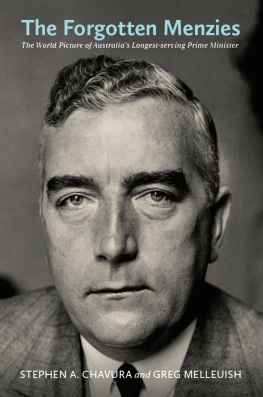

The Forgotten Menzies

The World Picture of Australias Longest-serving Prime Minister

STEPHEN A. CHAVURA

and

GREG MELLEUISH

MELBOURNE UNIVERSITY PRESS

An imprint of Melbourne University Publishing Limited

Level 1, 715 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia

www.mup.com.au

First published 2021

Text Stephen A. Chavura and Gregory Melleuish, 2021

Design and typography Melbourne University Publishing Limited, 2021

This book is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means or process whatsoever without the prior written permission of the publishers.

Every attempt has been made to locate the copyright holders for material quoted in this book. Any person or organisation that may have been overlooked or misattributed may contact the publisher.

Text design and typesetting by Adala Group

Cover design by Philip Campbell Design

Printed in Australia by McPhersons Printing Group

9780522877687 (hardback)

9780522877694 (ebook)

CONTENTS

To deal adequately with so vast a subject as the disintegration of Puritanism would require a Gibbon.

Hugh Kingsmill, After Puritanism

We are, in the Pauline sense, in bondage to the law and can emerge from it only by the exercise of personal responsibility.

F.W. Eggleston, Search for a Social Philosophy

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank the following people for reading parts of the manuscript or discussing the contents and improving the argument: Ian Tregenza, Malcolm Prentis, David Bebbington, Geoff Treloar and Stuart Piggin. We are grateful to Nathan Hollier at Melbourne University Publishing for his interest in the book, as well as Louise Stirling and Cathryn Game for skilfully getting the book to press. We also thank the anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on the draft manuscript.

With permission from the publishers, this book draws on parts of the following publications:

Chavura, S.A., Culture, utility and critique: The idea of a university in Australia, in Campus Meltdown: The Deepening Crisis in Australian Universities, ed. W.O. Coleman, Connor Court, Redland Bay, Qld, 2019, pp. 21331

The Christian social thought of Sir Robert Menzies, Lucas: An Evangelical History Review, vol. 2, no. 12, pp. 1946

Chavura, S.A. & G. Melleuish, The forgotten Menzies: Cultural puritanism and Australian social thought, Journal of Religious History, vol. 44, no. 3, 2020, pp. 35675

Melleuish, G., Why there are history wars, Dorchester Review, vol. 2, no. 2, 2012, pp. 603

INTRODUCTION

Sir Robert Menzies (18941978) was Australias longest serving Prime Minister. He had two periods of office, from 1939 to 1941 and from 1949 to 1966. As well, he exerted a major influence within the Lyons government from 1934 to 1939 in which he served as Attorney-General. There can be no doubt that Menzies as an individual had a major influence on the development of twentieth-century Australia, overseeing considerable change in the 1950s and in the first half of the 1960s as the country was transformed in a range of ways, from the implementation of a program of mass immigration to the expansion of its secondary industry to an overhaul of its educational institutions to dissolution of many of its links to Britain. At a time of considerable change, Menzies appeared to be a rock of stability, a permanent feature of the political landscape, who could assure the Australian people that in a world of change there was something permanent and stable about life in Australia. He was aided in this by the growing prosperity of the country after 1949, a prosperity that was embraced by Australians, many of whom had experienced two world wars and the Great Depression. It seemed as if Australia was being kept on track by a kindly old uncle.

The traditional, somewhat old-fashioned demeanour that Menzies cultivated led many of his criticsmost famously Donald

In recent times, the Liberal Party has attempted to reclaim the Menzies heritage and to portray him as the fount of the liberal values of the modern Liberal Party. This has been a welcome antidote to the caricature of Menzies, which has often been projected by their political opponents, but which has also expressed certain confusions of its own. Most famously, in 2017 Liberal Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull stated that neither Menzies nor the Liberal Party were ever conservative.quoted the line in Menzies autobiography, Afternoon Light, in which Menzies explained why he called his party the Liberal Party (rather than the Conservative Party): We took the name Liberal because we were determined to be a progressive party, willing to make experiments, in no sense reactionary but believing in the individual, his right and his enterprise and rejecting the socialist panacea.

Political scientist and columnist Peter Van Onselen defended Turnbulls view, reprinting the Menzies quote above, glossing: Take the opportunity to re-read that quote, reminding yourself how often Menzies is incorrectly referred to as a champion of conservatism: determined to be a progressive party. Not a lot of ambiguity in that. This wide dichotomy between liberalism and conservatism that informs the analyses of Turnbull and Van Onselen is terribly anachronistic, a mere projection of a wedge between conservatism and liberalism that has emerged relatively recently in Australian history.

David Kemp is far more informative in saying that Menzies individualist liberalism came rather from his legal theory and his Scottish/Presbyterian background.

There is a danger in reading Menzies wartime speeches, collectively published in The Forgotten People (1943), as if they embodied the values and ideas of early twenty-first-century liberalism and/or conservatism. Menzies was a product of a particular time and place, and he needs to be understood in terms of the values and ideas of that time and place. For example, much of his memoirs is dedicated to discussing the British Commonwealth of Nations, and by the late 1960s he was undeniably concerned about the fate of the Commonwealth. In fact, Menzies was a loyal child of the British Empire/Commonwealth; he was simultaneously British and Australian, which is to say that he was British in an Australian way, just as his near contemporary W.K. Hancock wrote about independent British Australians.

What needs to be recovered is an understanding of Menzies in his own terms rather than as a pawn in a modern ideological war within the party he started. Menzies saw himself less as an ideological warrior than as a defender of a tradition embodying both ideas and a way of doing things that he feared was being killed off by a number of cultural, economic and political developments that he believed would come to characterise the twentieth century. He lived through some of the most terrible years in modern history. If anything, he believedat least late in lifethat the age of ideologies was over. Like a good nineteenth-century liberal, Menzies seems to have associated liberalism with good government, not with an ideology.