Contents

Guide

This edition published in 2018 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

First published by Birlinn in 1999

Reprinted 2010, 2014

Introduction copyright Charles W.J. Withers 1999

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 978 1 78027 546 8

eBook ISBN 978 0 85790 288 7

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A Catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Typeset by Geethik technologies, India

Printed and bound by MBM Print SCS Ltd, East Kilbride

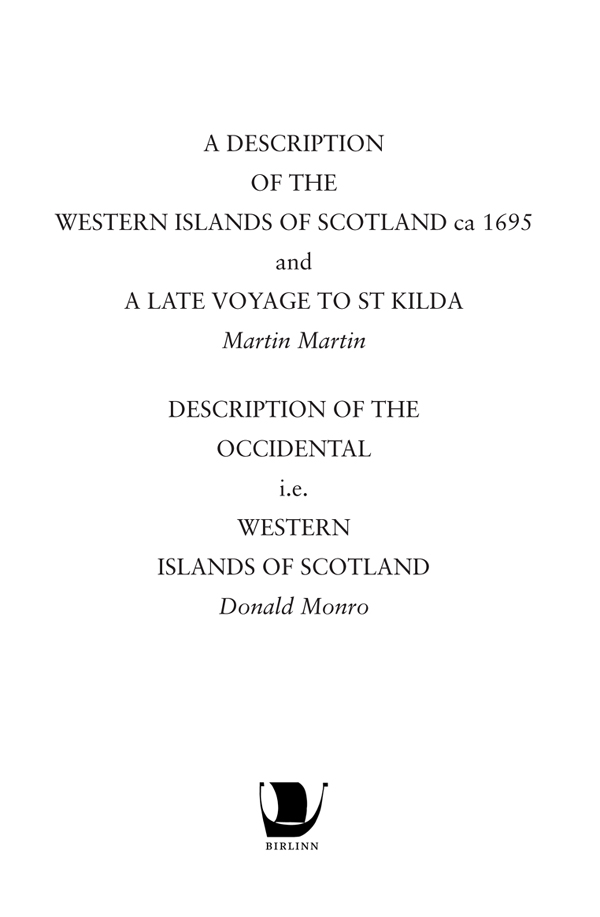

CONTENTS

A DESCRIPTION OF

THE WESTERN ISLANDS

OF SCOTLAND CA. 1695

Martin Martin

A LATE VOYAGE TO ST KILDA

Martin Martin

DESCRIPTION OF THE OCCIDENTAL

i.e.

WESTERN ISLES OF SCOTLAND

Donald Monro

A DESCRIPTION

OF THE

WESTERN ISLANDS OF SCOTLAND ca 1695

Introduction

Charles W. J. Withers

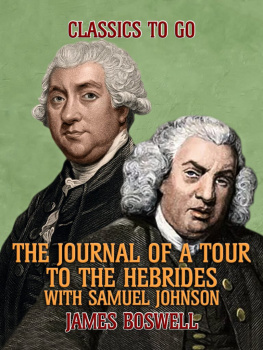

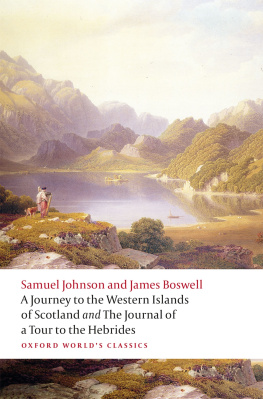

Martin Martins A Voyage to St Kilda (1698) and A Description of the Western Isles of Scotland (1703) are amongst the first printed works to describe the Hebrides and the culture and beliefs of the people of Scotlands Outer Isles. For this reason alone, they are noteworthy. Some modern commentators consider Martins Hebridean narratives the definitive forerunner to those topographical accounts of Scotland in general and of the Highlands in particular that are so common from the later eighteenth century. Later travellers, it is true, were influenced by the works. Martins Description of the Western Isles was given to Samuel Johnson by his father, a fact which roused the doctors interest in Scotland and prompted his own tour with James Boswell. Influenced Johnson may have been: impressed he was not. No man, wrote Johnson, now writes so ill as Martins account of the Hebrides is written. Boswell was only slightly more charitable: His Book is a very imperfect performance; & he is erroneous as to many particulars, even some concerning his own Island. Yet as it is the only Book upon the subject, it is very generally known... I cannot but have a kindness for him, not withstanding his defects. Earlier, the antiquarian and natural historian John Toland had noted of Martins Hebridean works that The Subject of this book deservd a much better pen... [These] Islands afford a great number of materials for exercising the talents of the ablest antiquaries, mathematicians, natural philosophers, and other men of Letters. But the author wontes almost every quality requisite in a Historian (especially in a Topographer).

What, then, are we to make of these early, and, seemingly, erroneous and imperfect yet influential texts? It is vital to recognise, of course, that Johnson, Boswell and Toland were judging Martin and his work from the standards of their time, not his. Seen in terms of that more precise rhetoric which informed later eighteenth-century literary and geographical description, Martins texts might indeed be judged an imperfect performance. He himself admitted to Defects in my Stile and way of Writing, and confessed that he might have put these papers into the hands of some capable of giving them, what they really want, a politer turn of phrase. It is not appropriate, however, to judge the products of one age by the standards of another. Further, given the existence of earlier accounts of the Western Isles, albeit that many survived only in manuscript form, from Dean Monros 1549 Description of the Western Isles of Scotland included here in full (pp. 315378) and other geographical documents dating from the 1640s, 1670s and 1680s, the view that Martins accounts mark the beginning of topographical description of the Hebrides cannot be allowed to stand.

Judged in the context of their own time, Martin Martins works have considerable significance and are of interest to the modern reader for three reasons. First, Martin Martin, as a Skye native and a Gaelic speaker, is of the places and peoples he writes about. His work is of importance, then, not just because it is an early account but, crucially, because it is by a native. What we get is a credible account of St Kilda and of the Hebrides from, as it were, the inside, and, in that regard, Martins works are unlike virtually any other commentary on the Highlands and Islands.

Second, what Martin Martin gives us is a view of Hebridean culture and society before the Highlands and Islands of Scotland get invested with those false yet persistent images of tartanry, romance, Bonnie Prince Charlie and the aesthetic majesty of empty landscapes that so mark commentators works from the end of the eighteenth century. In this regard, too, Martins accounts of the lives of ordinary people and of their customs and beliefs do not seek, as was so common in many later writers concerned with their own moral authority as improvers, to judge the people he is writing about. This is not to say the world he was writing about should be seen either as some sort of authentic and timeless Hebrides, or that that world was untouched by things going on elsewhere. This was far from the case.

Third, Martin was both part of, and an agent for, a different and wider world altogether. His works were largely written at the behest of influential members of the Royal Society, the London-based institution that was, from its foundation in 1660, crucial to the development of modern scientific methodology. It is also the case that they were written in the face of competition from other people, notably John Adair the map-maker. Further, Martin was bound up with those networks of natural knowledge at that time centring upon Sir Robert Sibbald, the Geographer Royal for Scotland, who was using local informants information to pull together a geographical description of Scotland as a whole. Martin was, then, both a local man, and, by the terms of his own day, a practising scientist with national connections.

Science at this time, or natural philosophy as it should more properly be called, was greatly dependent upon travellers reports of unknown lands and peoples. What was geographically unknown at this time did not simply mean distant places and strange peoples far away. It included the foreign near at hand. The Highlands and Islands of Scotland were certainly unknown to most people, even to other Scots. Martin commented on just this point: Foreigners, sailing thro the Western Isles, have been tempted, from the sight of so many wild Hills... and facd with high Rocks, to imagine the Inhabitants, as well as the Places of their residence, are barbarous;... the like is supposd by many that live in the South of Scotland, who know no more of the Western Isles than the Natives of Italy. To members of the Royal Society men like Robert Boyle who had published guidelines in 1692 to travellers on the sorts of things they should comment upon, and, indeed, on the proper ways for a gentleman abroad to conduct himself in making such enquiries Hebridean Scotland was indeed unknown. All knowledge about such places was welcome, especially if one could get a reliable and trustworthy reporter.