Contents

Guide

ISLANDS OF

SCOTLAND

Pat Morgan

Contents

Introduction

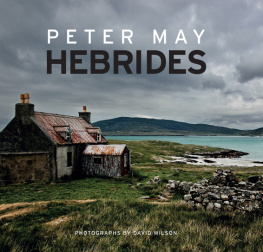

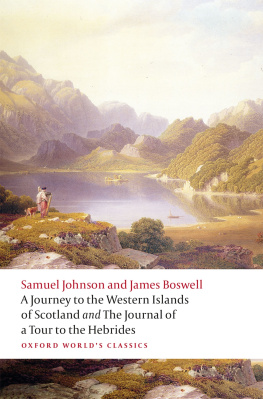

D uring the late summer and autumn of 1773, the elderly Samuel Johnson, accompanied by his friend James Boswell, journeyed throughout the islands of the Hebrides off the west coast of Scotland. The two writers travelled by horseback, coach and boat, staying with the local gentry and observing places and people that bore little resemblance to the relative comforts of the cities to which they were more accustomed. Johnson published his impressions in his 1775 volume A Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland, while Boswell recorded his impressions of Johnson in 1785 with the publication of A Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides.

The two authors were not the first travellers to be attracted to Scotlands islands by the prospect of wild beauty, splendid isolation and alien cultures, but they served to bring the attention of the wider world to some of the worlds great wonders. They did not venture beyond the Hebrides, and thus missed out on the glories of many hundreds of islands that adorn Scotlands coast, but they provoked a desire in many a would-be tourist to visit places that, even now, can seem separated from the rest of Britain by more than just water.

The isles of Scotland, each one its own little world with its own distinct nature, form one of the worlds most magical attractions. There are probably too many for any one traveller to explore thoroughly in a lifetime, though some have tried. There are too many for this book to cover in detail, and the most we can hope to do is to offer some highlights of the myriad on offer.

There are, all told, more than 790 offshore islands scattered round the 6,000 miles of Scotlands coastline. They range from the sizeable, such as Lewis and Harris in the Outer Hebrides, to tiny outcrops of rock that barely seem worthy of the name of island; from the rugged and mountainous to the lower-lying and serene; from the seemingly impossibly remote to those that are linked to the Scottish mainland by a bridge. Every single one of those islands has its own personality and character and every single one is worth a visit. If only there were the time

Most readers will be familiar with the names of the four main groups of islands: Orkney, Shetland, the Inner Hebrides and the Outer Hebrides. Also to be taken into consideration are smaller groups of islands in the Firth of Forth, on Scotlands east coast, in the Solway Firth to the south-west and in the Firth of Clyde in the west. Many can be accessed by regular ferry or air services or bridge, while friendly boat or aircraft owners can sometimes be persuaded to drop off intrigued travellers. Most of the larger islands offer hotel accommodation and hundreds of others offer bed-and-breakfasts, campsites or hostels.

The main attractions are those that are visited by many thousands of tourists each year: Skye, Mull, Arran, Lewis and Harris, Islay, some of the larger islands of Orkney and Shetland and the like. Further off the beaten tourist track are such delights as Benbecula, Colonsay, Eriskay, Great Cumbrae and Jura. Exploration of the lesser known will be rewarded handsomely.

Lewis and Harris one of the worlds favourite islands

Whats the story? Tobermory, Mull

Throughout the islands you will come across reminders of the languages that have been spoken here throughout the ages, in the names of the places you visit. Four languages have been at play in the formation of place names: English, Gaelic (still spoken, in different forms, in parts of Scotland and Ireland), Norse (a remnant of the Viking era) and Brythonic (an older Celtic language than Gaelic, represented today in the Welsh and Breton tongues). Whenever you come across an island name that ends in ay (and there are plenty of them), you will know that the Norsemen were there: its simply the Norse word for island. English, on the other hand, took a long time to reach the islands, and its influence has been small. The Gaelic for island eilean is widely represented, and other Gaelic words you are bound to come across include mr (big), bn (white) and dubh (black).

What to do once you have taken your ferry, driven over a bridge or skimmed the waves in an aircraft to discover your island paradise? The possibilities are endless: don walking boots and new worlds will open up to you; if youre of an even more adventurous nature a spot of mountain trekking will be your thing; you might want to revel in the hospitality of the towns and villages that dot the islands, taking in a bit of local culture; perhaps you will want to marvel at your islands rewarding wildlife, explore a historic castle or two or even bask in a gorgeous sunset on a white-sanded beach.

Maybe you will want to discover a mysterious prehistoric site. You will doubtless be keen to sample the local cuisine and take a dram or several of some of the finest whiskies Scotland has to offer, each possessing a character all of its own. Perhaps you will be content to sit and wonder at the landscape that presents itself mountain or moorland, loch or river, cliff or beach or marvel at the majesty of the sea.

Confirmation that the Scottish isles offer a world of possibilities came in 2014 when travellers voted three of them Lewis and Harris, Mainland Orkney and the Isle of Mull into the top 10 in awards for islands in Europe, and Lewis and Harris into fifth place in the global pantheon. Those voters, wise people all, preferred the cliffs and beaches of Lewis and Harris to the wonders of the Seychelles; the Neolithic remains and gorgeous scenery of Orkney to the charms of the Balearic Islands; the multicoloured main street of Tobermory, Mulls principal town, to anything the Canaries have to offer.

In sun and rain, in summer or winter, night or day, the islands of Scotland have something for everyone who has romance in their soul, as the following pages will show. We will start our journey around the coast of Scotland in the far south-west but first examine their history and geography.

Chapter 1

History & Geography

T he story of the islands that form a rocky ring around Scotland mirrors in many ways the story of Scotland itself.

Some scholars believe that early humans inhabited parts of the country as early as 40,000 years ago, although the evidence for that theory is scant. Following the retreat of the mighty glaciers that covered much of Britain during the last Ice Age, around 15,000 years ago, humans began to inhabit Scotland in meaningful numbers, and flint artefacts around 12,000 years old have been found in what is now Lanarkshire. The first signs of settled habitation, dated to 8,500 years ago, have been discovered near Edinburgh on the mainland. Although there is evidence of domesticity, these early Scots seem to have been mobile and may have moved from site to site as the seasons changed. They used boats for transport and fishing and moved inland from the coasts to hunt using stone weapons.