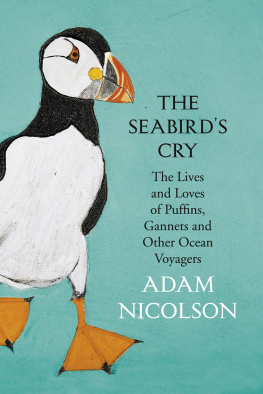

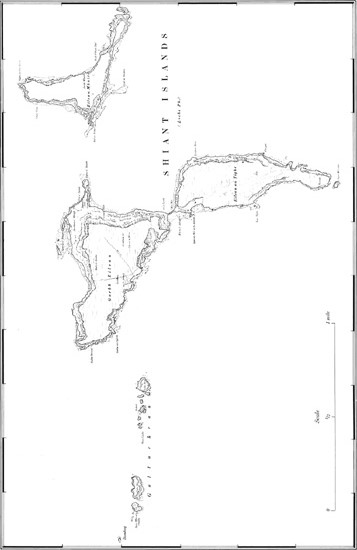

FOR THE LAST TWENTY YEARS I have owned some islands. They are called the Shiants: one definite, softened syllable, the Shant Isles, like a sea shanty but with the y trimmed away. The rest of the world thinks there is nothing much to them. Even on a map of the Hebrides the tip of your little finger would blot them out, and if their five hundred and fifty acres of grass and rock were buried deep in the mainland of Scotland as some unconsidered slice of moor on which a few sheep grazed, no one would ever have noticed them. But the Shiants are not like that. They are not modest. They stand out high and undoubtable, four miles or so off the coast of Lewis, surrounded by tide-rips in the Minch, with black cliffs five hundred feet tall dropping into a cold, dark, peppermint sea, with seals lounging at their feet, the lobsters picking their way between the boulders and the kelp and thousands upon thousands of sea birds wheeling above the rocks.

In summer, the grass on the cliff-tops is thick with flowers: bog asphodel and bog pimpernel; branched orchids, the stars of tormentil and milkwort. Under such skies can be expected no great exuberance of vegetation, Dr Johnson wrote, but this miniature spangle of Hebridean flora, never protruding its yellows and deep purples more than an inch or two above the turf, is a great and scarcely regarded treasure. I think of it when in England I walk on expensive Persian rugs; the same points of dense, discreet colour, the same proportion of ground to decoration; a sudden flash of the Hebrides in a rich mans rooms. It is a private signal to me, a bleeping underfoot, winking through the burr of conversation and offered drinks: Remember me.

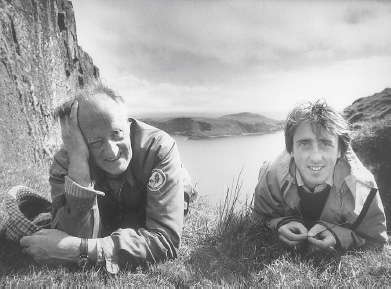

At times in the last two decades, these islands have been the most important thing in my life. They are a kind of heartland for me, a core place. My father bought them over sixty years ago for 1,400, he gave them to me when I was twenty-one, and I shall give them to my son Tom when he is twenty-one in four years time. This is not, as cynics have sometimes said, for tax reasons. The Shiants seem scarcely to do with money and, anyway, they have been a catastrophic investment. For the same amount, at the same time, my father could have bought a Jacobean manor house in Sussex or a two hundred-acre farm of prime arable in Cambridgeshire. Each would be worth a million or more by now. As it is, if I sold the Shiants, I could perhaps buy a two-bedroom flat in Fulham.

This was never a question of financial riches. My father bought the islands and gave them to me because as a very young man he had felt enlarged and excited by the ownership of a place like this, by the experience of being there alone or with friends, by an engagement with a nature so unadorned and with a sea- and landscape so huge that it allowed an escape into what felt like another dimension. It was a way of leaving home, a step into a different world. He described this, fitfully, in a letter to his brother Ben on first going there in 1937: I would wake up the next morning to find the sun in a sky as pure as a Bavarian virgin, the twenty-year-old Balliol undergraduate half-joked.

I would lie all morning with no clothes on, on a rock overlooking the sea, reading and annotating Hegel. In the afternoons I used to run bare-footed across the mile of heather to the edge of the northern cliff, there flinging myself down, to read, or write, or gaze out to sea thinking about life, and what Heaven this was. The view from the top is such that only Greece could parallel.

And then he torpedoed it, embarrassed: One becomes very Golden Bough in these conditions, Im afraid.

For all the camouflage, the experience was real, and forty years later he wanted, I think, to give that same enlargement to me: that wonderful sea room, the surge of freedom which a moated island provides. The gift was this: the sensation I can now summon, anywhere and at any time, of standing in the pure air streaming in off the Atlantic, alone on these islands which the last inhabitants left a hundred years ago. I have peered at them in every cranny: I have hauled lobsters and velvet crabs from the sea; picked the edible dulse from the walls of the sea caves and of the great Gothic natural arch which perforates a narrow horn of one of the islands; scrambled among the hissing shags and looked down the dark slum tunnels where the puffins live and croak their curious, endearing note, like a heavy door opening on a rusted hinge; and I have lain down in the long grass while the ravens honked and flicked above me and the skuas cruised in a milk-blue sky. I have felt at times, and perhaps this is a kind of delirium, no gap between me and the place. I have absorbed it and been absorbed by it, as if I have had no existence apart from it. I have been shaped by those island times, and find it difficult now to achieve any kind of distance from them. The place has entered me. It has coloured my life like a stain. Almost everything else feels less dense and less intense than those moments of exposure. The social world, the political world, the world of getting on with work and a career all those have been cast in shadow by the scale and seriousness of my brief moments of island life.

There was a time when I thought that to give the islands away, even to Tom, would be an unbearably difficult thing. Sometimes, away from them, late at night in strange hotels, I would listen to the shipping forecast Hebrides, Minches, Storm Force Ten, backing southwesterly, sleet, visibility two hundred yards. I would think of them then, wet, battered and impossible, the rain slinging itself in handfuls of rice against the windows of the bothy, the churning of the sea, when, as it says in a famous Gaelic poem, The whorled dun whelk that was down on the floor of the ocean,/Will snag on the boats gunwales and give a crack on her floor, when the cowering birds would be tucked in behind the boulders, and the sheep would be enduring the storm with the patience of saints and the dignity of martyrs. Those were the moments, not in their presence, when I felt most deeply attached to them. The Shiants are the most powerful absence I know. On every flight across the Atlantic, I would peer out for them, looking for an opening in the clouds to see them there, still and map-like below me, with the sea sheened and glittery around them, while the stewardess handed out headsets and warm towels. That too would be a moment of dreaded loss.

That has changed now. I have changed and I do not, I think, need them as much as I once did. The gift I received is the gift I want to make. They are a young mans place and always have been. Tom will have his time there too, with his own friends and his own discoveries. He will know the Shiants in ways different from his fathers and grandfathers. A place evolves in the minds of the people who possess it and it is Toms turn now.

This book is my final immersion in them. I have tried to get to know them as I have scarcely done before. No one previously has written at any length about the Shiants and this is both an opening and, for me anyway, a closing of their account. It is an attempt to tell the whole story, as I now understand it, of a tiny place in as many dimensions as possible: geologically, spiritually, botanically, historically, culturally, aesthetically, ornithologically, etymologically, emotionally, politically, socially, archaeologically and personally. It is a description of what my father gave to me and of what, in the spring of 2005, I shall give to my son.